Populism is on the rise, according to the latest edition of the Authoritarian Populism Index. The index, an initiative of the Swedish think-tank Timbro, aims to determine to what extent populist parties threaten liberal democracy in the European Union and five other countries on the continent:

The three parties included in the index that achieved the highest support in the last elections were: Fidesz (Hungary), Law and Justice (Poland), and Syriza (Greece). At the end of 2018, the support for populist groups in the three countries exceeded 50%, based on the results of the last elections, and these were: Hungary, Greece, and Italy. Poland ranked fourth in terms of support for populists (PiS and Kukiz’15).

The three parties included in the index that achieved the highest support in the last elections were: Fidesz (Hungary), Law and Justice (Poland), and Syriza (Greece). At the end of 2018, the support for populist groups in the three countries exceeded 50%, based on the results of the last elections, and these were: Hungary, Greece, and Italy. Poland ranked fourth in terms of support for populists (PiS and Kukiz’15).- In many countries, populist parties are opposition parties and traditional political parties refuse to cooperate with them. However, as many as 11 countries have populist parties ruling or co-ruling. These are: Hungary, Poland, Greece, Norway, Finland, Italy, Latvia, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Switzerland, and Austria.

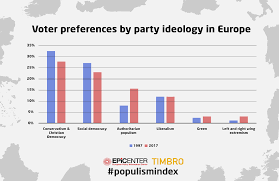

In the latest edition of the index, the average support for parties classified as populist in 33 European countries was just over 22%, and such groups gained the support of about 71 million voters (27%).

In the latest edition of the index, the average support for parties classified as populist in 33 European countries was just over 22%, and such groups gained the support of about 71 million voters (27%).

The rise of authoritarian populism features in the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy, including:

- How did Brazil’s democracy pave the way for the rise of Jair Bolsonaro? Wendy Hunter and Timothy J. Power investigate the far-right populist’s path to the presidency.

Roberto D’Alimonte considers how Italy’s populists came to power, and what their victory portends;

Roberto D’Alimonte considers how Italy’s populists came to power, and what their victory portends;- Aqil Shah examines the alliance with the military that helped to bring about populist Imran Khan’s electoral win in Pakistan.

Timbro uses the category of “authoritarian populism” to distinguish parties in which some populist demands appear from those which express opposition to the model of constitutional liberal democracy (for instance, lack of acceptance for the separation of powers and restraints on power, hostility towards procedures existing in democracy, developing conflicts between homogeneous “people” and “elites”).