Don’t flatter the west’s enemies as an ‘axis’ https://t.co/rafK01EliC via @ft

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) October 24, 2023

After the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for the Russian President on war-crimes charges, Vladimir Putin hosted Xi Jinping in Moscow, where they described relations as the best they have ever been, The New Yorker’s Evan Osnos writes. Clasping hands for a farewell in the doorway of the Kremlin, Xi told Putin, “Right now there are changes—the likes of which we haven’t seen for a hundred years—and we are the ones driving these changes together.” Putin responded, “I agree.”

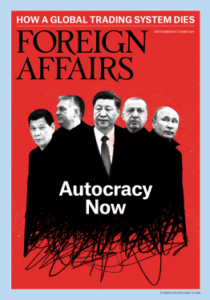

With the Middle East embroiled in its worst conflict in decades and Russia’s war on Ukraine continuing, Chinese president Xi Jinping is confidently asserting his role as the leader of a new authoritarian bloc, the International Republican Institute’s Daniel Twining and Matt Schrader observe. This was on full display in Beijing when leaders from more than 130 countries convened to celebrate ten years of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the investment and infrastructure program central to Xi’s global influence campaign, they write for National Review.

But is it a mistake to refer to disparate autocratic regimes in terms of an authoritarian bloc or axis?

But is it a mistake to refer to disparate autocratic regimes in terms of an authoritarian bloc or axis?

The democratic West is a coherent entity, held together with treaties and institutions which predate several of the world’s nation states, notes Financial Times analyst Janan Ganesh:

Nato has been around since 1949, the European project for almost as long. Neither is just a forum for chatter: one commits its members to mutual defence, the other subjects domestic to supranational law. That is, western countries are willing to foot a bill — in membership fees, sovereign freedom and ultimately blood — for their geopolitical team. The west isn’t just broad (and getting broader, as both Nato and the EU process applications to join). It is also deep.

Its rival bloc – a grouping as loose and putative as Russia, China, Iran and North Korea – is the first of these things, without question, but not the second. What, after all, unites the four? Ganesh asks:

Its rival bloc – a grouping as loose and putative as Russia, China, Iran and North Korea – is the first of these things, without question, but not the second. What, after all, unites the four? Ganesh asks:

The group includes secular communists and the world’s leading theocracy. The two largest members fell out with each other in the cold war…. There are jabber-fests that bring most of the members together, such as the Brics-plus summit, but no Nato- or EU-grade institution that requires tangible sacrifices from those who belong. And what is their shared view of global economic governance? What is the “Moscow consensus”? State sovereignty, at least, used to be the one shibboleth of autocrats. Since the invasion of Ukraine, and the tolerance of it in parts of the world, does even that still hold?

The foreign policy of the free world over the coming years has to be a patient game of teasing out the contradictions within the autocratic world: between theologians and commissars, between closed economies and trading ones, between rising powers and fading ones, between states with extensive contact with the west and total outcasts, Ganesh asserts. RTWT

The world built from the ashes of WWII & the Cold War is at risk of fracturing in the face of coordinated #authoritarian aggression, with alarming consequences for U.S. national security, @NEDemocracy partner @IRIglobal‘s @DCTwining told @HelsinkiComm. https://t.co/ezyaqB0I0C

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) October 24, 2023