The experience of Afghanistan over the past 20 years illustrates the problems and contradictions inherent in the democracy-promotion agenda, The Economist Intelligence Unit’s annual Democracy Index asserts.

The issue of how to define democracy is not only of academic interest, it adds. For example, although democracy promotion is high on the list of US foreign-policy priorities, there is no consensus as to what constitutes a democracy. As one observer put it: “The world’s only superpower is rhetorically and militarily promoting a political system that remains undefined—and it is staking its credibility and treasure on that pursuit.”

But the key to advancing democracy lies in flexible and focused responses to grass-roots demands, said Belarus opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya. It’s vital that international assistance reflects genuine needs and “reaches the activists on the ground,” she told the Josef Korbel School’s Democracy Summit (above).

The democratic upsurge in Belarus amounted to a popular “awakening” that confirmed the “extraordinary resilience of the demand for democracy,” said Damon Wilson, President and CEO of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). Developments in Ukraine also demonstrate that despite Putin’s efforts to export the tools of autocracy – what’s become known as The Dictator’s Learning Curve – “the façade has gone” and the people’s democratic aspirations “can’t be put back in the bottle,” he told the forum.

Happening now at the #Denver #Democracy #Summit: @DamonMacWilson + @Tsihanouskaya on “Democratic Resistance: A Global Perspective”https://t.co/v7FD58KxfL #DefendDemocracy #DDS2022 @AoDemocracies pic.twitter.com/ZDLfHkTagI

— NEDemocracy (@NEDemocracy) February 10, 2022

Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Anne Applebaum contends that Putin has strategic and ideological ambitions that go far beyond Ukraine:

He wants to destabilize Ukraine, frighten Ukraine. He wants Ukrainian democracy to fail. He wants the Ukrainian economy to collapse. He wants foreign investors to flee. He wants his neighbors—in Belarus, Kazakhstan, even Poland and Hungary—to doubt whether democracy will ever be viable, in the longer term, in their countries too. Farther abroad, he wants to put so much strain on Western and democratic institutions, especially the European Union and NATO, that they break up. He wants to keep dictators in power wherever he can, in Syria, Venezuela, and Iran.

Left-leaning critics accuse the West of double standards, as David Bromwich argues in The Nation:

Ukraine shares a border with Russia the way Mexico and Canada do with the United States. Since 1823, we have claimed the right to defend our hemisphere in accordance with the Monroe Doctrine, and now Russia is putting into practice a similar policy against a militarized Ukraine…. Yet Secretary of State Antony Blinken has said the US no longer believes that there are spheres of influence. Or rather, there is just one sphere: the ever-expanding terrain of legitimate Western democracies approved by NATO.

In some countries, particularly Germany, Europe functions effectively as an ideal, a justification for the pragmatic pursuit of national interests and an advantageous set of political and economic structures, notes Cambridge University professor Helen Thompson, author of Disorder: Hard Times in the 21st Century. But in others, especially Ukraine, citizens might identify imaginatively with Europe, but enjoy few, if any, accompanying political benefits. Left outside real-world Europe, Ukraine must confront the historical tragedy of the deep tension between the idea of European identity and the possibilities for organizing political life around it, she writes for The New Statesman.

In some countries, particularly Germany, Europe functions effectively as an ideal, a justification for the pragmatic pursuit of national interests and an advantageous set of political and economic structures, notes Cambridge University professor Helen Thompson, author of Disorder: Hard Times in the 21st Century. But in others, especially Ukraine, citizens might identify imaginatively with Europe, but enjoy few, if any, accompanying political benefits. Left outside real-world Europe, Ukraine must confront the historical tragedy of the deep tension between the idea of European identity and the possibilities for organizing political life around it, she writes for The New Statesman.

Western observers think of Putin as anachronistic only because we have convinced ourselves that we have moved beyond his form of power politics, based on raw national interest, to something post-national, Thompson tells The Atlantic’s Tom McTague:

The problem is that while overt displays of nationalism are now viewed as somewhat distasteful, passé, and dangerous in the West, the nation-state itself remains the foundation not just of international relations, but of Western democracies. As Thompson said, for the people to choose their representatives, there has to be a people in the first place, and historically the nation has defined who any particular democratic people is. Democracy and nationalism, in other words, go hand in hand.

Consequently, McTague suggests, the resurgence of autocratic powers like Russia and China in a newly multipolar world challenges the complacent teleological assumption that the future entails progress:

Suddenly, we are forced to confront the prospect that in the future we may not have “progressed” toward some more enlightened, just, and universal order. Instead, the future might be more particular, competitive, national, or perhaps even civilizational. And if that is the case, what happens if we are on the wrong side of history, not because we were necessarily wrong but because we just got beat?

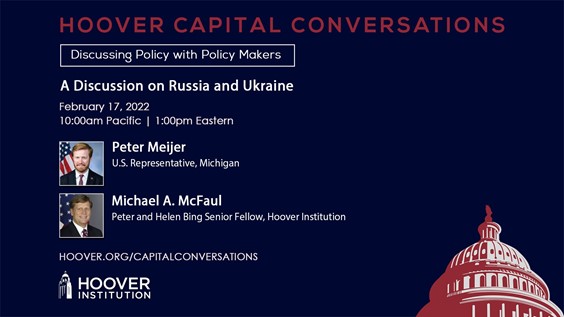

Hoover Capital Conversations: A Discussion on Russia and Ukraine on February 17, 2022.

Hoover Capital Conversations: A Discussion on Russia and Ukraine on February 17, 2022.

Former US Ambassador to Ukraine Bill Taylor and Ambassador Paula Dobriansky of the Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center discuss whether diplomacy and democracy can prevail in the Ukraine-Russia crisis (below).