Credit: Carnegie

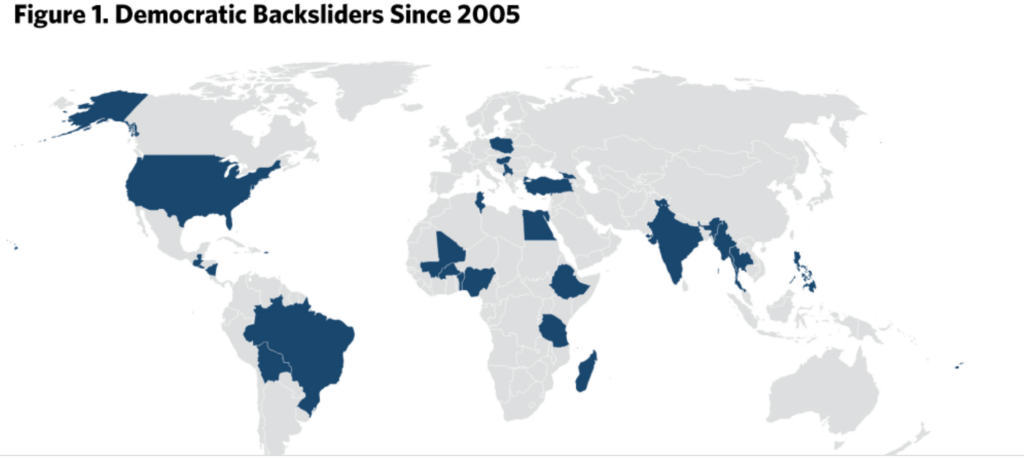

At the beginning of 2022, all democracy indices indicated that the world’s democratic recession was continuing, according to Ken Godfrey, executive director of the European Partnership for Democracy. In this context, the EU and national governments faced the challenge of countering democratic backsliding and authoritarian influence, and they framed many policies accordingly in defensive fashion, he writes for Carnegie Europe’s annual review of democracy support.

According to the United Nations Development Programme, there were fifty-four developing countries with severe issues in managing debt, amid fears of a global recession, adds his EPD colleague Evelyn Mantiou. The resulting instability was particularly detrimental to young democracies and threatened to set back democratic progress.

Former NED board member Francis Fukuyama

Yet Francis Fukuyama was more right than he has been given credit for about the popular and intellectual triumph of democratic philosophy. A world where democracy is dominant may be more volatile and unpredictable than we understood, The Washington Post’s Jason Willick suggests.

“Despite the general narrative that we are in a period of global democratic decline, there have been surprisingly few empirical studies to assess whether this is systematically true,” political scientists Andrew Little of the University of California at Berkeley and Anne Meng of the University of Virginia write in a new research paper. “Most existing studies of backsliding rely heavily, if not entirely, on subjective indicators which rely on expert coder judgement. We survey other more objective indicators of democracy (such as incumbent performance in elections), and find little evidence of global democratic decline over the last decade,” they conclude in “Subjective and Objective Measures of Democratic Backsliding.”

Little and Meng find that the post-Cold War expansion of democracy in nations around the world has, on average, held, Willick writes:

They find, for example, no overall decline in electoral competition. Across the world, “The rate of leader and ruling party turnover has remained fairly constant since the late 1990s,” the paper says. “If anything, the vote shares of incumbent leaders in executive elections and incumbent parties in legislatures have decreased in recent years.”

They find, for example, no overall decline in electoral competition. Across the world, “The rate of leader and ruling party turnover has remained fairly constant since the late 1990s,” the paper says. “If anything, the vote shares of incumbent leaders in executive elections and incumbent parties in legislatures have decreased in recent years.”- They also measured the prevalence of constraints on national leaders, such as term limits. From 2000 to 2018, according to the paper, 60 leaders sought to evade term limits, and 34 succeeded, but the rate was “fairly constant” over time.

- In an attempt to objectively measure press freedom, the authors analyze data from the Committee to Protect Journalists. It’s a mixed picture: Murders of journalists have been declining since 2008, but the number of journalists imprisoned has been rising since 2000.

-

The authors created their own democracy index reaching back to 1980, relying on hard inputs such as the share of a population eligible to vote, rather than subjective interpretation by experts. “The index in 2020 is nearly as high as it has ever been,” they conclude.

Surveys from such reputable research groups as Freedom House, the Economist Intelligence Unit and Varieties of Democracy have highlighted what has become known as democratic regression, “autocratization” and/or what Stanford’s Larry Diamond christened “democratic recession.” But other research casts doubt on their findings.

Surveys from such reputable research groups as Freedom House, the Economist Intelligence Unit and Varieties of Democracy have highlighted what has become known as democratic regression, “autocratization” and/or what Stanford’s Larry Diamond christened “democratic recession.” But other research casts doubt on their findings.

Another study out this month helps explain the divergence between democratic perceptions and realities, Willick adds. The author, James D. Bryan, a doctoral candidate at American University, analyzed the World Values Survey and the European Values Survey between 2010 and 2022 to track how citizens’ understanding of democracy evolved under different political circumstances. His “findings suggest one’s conception of democracy can be a fluid attitude that citizens mold to match their partisan self-interest.” RTWT