Poland’s populist Law and Justice Party appears intent on imposing quasi-authoritarian control over its unruly democracy, analyst Max Boot writes for Commentary.

A new draft Law on Higher Education and Science — known as Law 2.0 — reflects Poland’s “broader authoritarian turn,” according to Mateusz Laszczkowski, assistant professor of political and economic anthropology at the University of Warsaw.

The most important counterweight to rising illiberalism in Poland lies in the country’s decentralized political structure, with its strong local governments, argues Wojciech Przybylski, editor-in-chief of Visegrad Insight and chair of the Warsaw-based Res Publica Foundation.

This built-in pluralism stands in the way of any single party’s efforts to impose a monolithic and centralized narrative. The principle of subsidiarity, if upheld and developed over time, will be the key element in curbing authoritarian ambitions on the part of any central government, he writes in Can Poland’s Backsliding Be Stopped?, an article in the latest edition of the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy.

This built-in pluralism stands in the way of any single party’s efforts to impose a monolithic and centralized narrative. The principle of subsidiarity, if upheld and developed over time, will be the key element in curbing authoritarian ambitions on the part of any central government, he writes in Can Poland’s Backsliding Be Stopped?, an article in the latest edition of the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy.

Even in what now seems the unlikely event that PiS suffers a defeat in the upcoming parliamentary elections (to be held by 2019) and that PO is able to form a coalition government, the legacy of Kaczyńnski’s dramatic changes to the Polish political system will remain an issue. Indeed, Kaczyńnski’s opponents could well view the more centralized system built up under PiS as a prize for the election winner, an instrument that they might use to construct a new variety of “democracy with adjectives”: a “liberal” democracy in which liberalism becomes a pretext for disregarding democratic norms. That scenario would be equally disastrous for genuine democratic openness and competition.

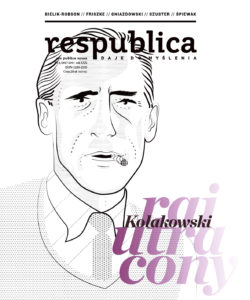

The current government has veered well away from the legacy of such celebrated Polish democratic advocates as Jan Nowak (see above) and Leszek Kołakowski (left), Poland’s foremost twentieth century philosopher, who “was on the side of the struggle for democracy and the rule of law,” says historian Andrzej Friszke, in conversation with ‘Res Publica Nowa’s’ Tadeusz Koczanowicz.

The current government has veered well away from the legacy of such celebrated Polish democratic advocates as Jan Nowak (see above) and Leszek Kołakowski (left), Poland’s foremost twentieth century philosopher, who “was on the side of the struggle for democracy and the rule of law,” says historian Andrzej Friszke, in conversation with ‘Res Publica Nowa’s’ Tadeusz Koczanowicz.

Kołakowski’s influence on the members of the Polish democratic opposition in the 70s was “absolutely fundamental,” mainly through the journal Paris Kultura, but also through certain texts and articles, he adds:

Every single intellectually active member of the opposition read Theses on Hope and Hopelessness [aka In Stalin’s Countries: Theses on Hope and Despair] published in 1971… Kołakowski shows what is inherent and what is potentially subject to change in communism seen as a system of power, not as an ideology.

In another crucial article, ‘Sprawa Polska’ [Polish Matter], Kołakowski argued for the importance of culture. It touched on the issue of the struggle for culture, language, and tradition as vital elements of the struggle for independence, freedom and democracy. These texts were extremely important and influential in forming the intellectual horizons of [our] democratic stance.

In another crucial article, ‘Sprawa Polska’ [Polish Matter], Kołakowski argued for the importance of culture. It touched on the issue of the struggle for culture, language, and tradition as vital elements of the struggle for independence, freedom and democracy. These texts were extremely important and influential in forming the intellectual horizons of [our] democratic stance.

The government’s illiberalism is also a far cry from the moral legacy of Jan Karski (right), a young Polish Catholic who witnessed Jews being put on cattle cars and who revealed the truth of the Shoah all the way to President Roosevelt himself. It’s fitting that Karski is the focus of a play from the Kreisau Project, whose focus is democracy and its resiliency.

“Saving Polish democracy will require unyielding pressure against illiberalism, but it will also depend on maintaining openness to debate and compromise,” Przybylski adds. “While finding the right balance will not be an easy task, it is a vital one for the future of democracy in Poland.”