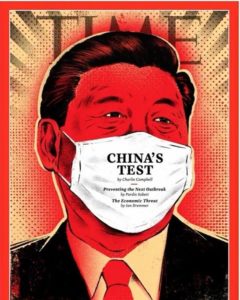

In the fall of 2017, Xi took the podium at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People to claim that China’s version of one-party autocracy offered an option for “countries that want to speed up their development while preserving their independence,” analyst Charlie Campbell reports. Western democracy was messy and flawed, the argument went. In the years since that speech, China’s hubris has grown, nurtured by the tumultuous U.S. presidency of Donald Trump and the disintegration of the multilateral world order. But the coronavirus crisis threatens to rattle China’s authoritarian apparatus, he writes for TIME.

The Chinese Communist Party’s prestige and legitimacy are both on the line as a result of what The Wall Street Journal’s Daniel Henninger calls the Communist coronavirus, analysts suggest. Crises like this are a serious test of the party’s assertions about the inherent superiority of China’s political system, argue Yun Jiang, a Senior Research Officer at Australian National University and Adam Ni, a China researcher at Macquarie University. Ultimately, the Chinese people are likely to judge the party harshly, despite its efforts at narrative control, they write for The Conversation.

TIME/Twitter

China’s top-down authoritarian political system makes things worse when it comes to emergencies like the coronavirus, notes Eurasia Group’s Ian Bremmer. In the early stages of these kinds of crises, local officials try to avoid blame from Beijing by hiding information about outbreaks and the extent to which health facilities are overmatched. In later stages of the crisis, they overcorrect to show Beijing they’ve taken charge of the problem, he writes for TIME.

Public health crises have a unique capacity to reveal the dark side of China’s success, adds analyst James Kynge. The frailties that have contributed to the hundreds of coronavirus deaths are as much a product of China’s authoritarian system as are the country’s extraordinary economic advances, he writes for The Nikkei Review.

For a brief time after the Cold War, we had indulged the illusion of – that democratic capitalism had triumphed and was now unchallenged by any competing ideology, adds James A. Lewis. That was nice while it lasted. But we are now in a new era of global tension and competition. And China has emerged as the United States’ top geopolitical adversary based on competing political and economic philosophies, he told today’s CSIS China Initiative Conference.

Much truth is revealed in a crisis. The continuing and ever-worsening effects of the coronavirus epidemic spark political facts about the true nature of the regime, according to Bradley A. Thayer, Professor of Political Science at the University of Texas San Antonio and the co-author of How China Sees the World: Han-Centrism and the Balance of Power in International Politics, and Lianchao Han, vice president of Citizen Power Initiatives for China.

Much truth is revealed in a crisis. The continuing and ever-worsening effects of the coronavirus epidemic spark political facts about the true nature of the regime, according to Bradley A. Thayer, Professor of Political Science at the University of Texas San Antonio and the co-author of How China Sees the World: Han-Centrism and the Balance of Power in International Politics, and Lianchao Han, vice president of Citizen Power Initiatives for China.

- First, the incompetence and the cover up are symptoms of the Leninist/Soviet/Maoist form of communist government. This type of regime is unable to address the problem because to do so threatens the legitimacy of the regime. The 1986 Chernobyl disaster was the masterclass of Soviet incompetence and cover up. …

- Additionally, the fear of an epidemic concentrates the mind and compels media attention to the failings and true nature of the regime for most Chinese people in a manner that other odious actions, such as the wide scale human rights abuses, including the suppression of freedoms, or Muslim re-education camps for Uighur and Kazakhs also reveal but have not compelled a similar level of response. ….

- Finally, China’s governing model has failed miserably. China has pretenses to lead global governance. This catastrophe demonstrates this absurdity, and the world is an unwilling witness to the consequences. …

Performance flaws in authoritarian systems are hidden until an economic slowdown, an environmental or public-health emergency, an international humiliation, or a corruption scandal comes along and makes them glaringly apparent, This can cause authoritarian legitimacy to decline suddenly and drastically, notes Andrew J. Nathan,* Class of 1919 Professor of Political Science at Columbia University and co-author of China’s Search for Security.

Performance flaws in authoritarian systems are hidden until an economic slowdown, an environmental or public-health emergency, an international humiliation, or a corruption scandal comes along and makes them glaringly apparent, This can cause authoritarian legitimacy to decline suddenly and drastically, notes Andrew J. Nathan,* Class of 1919 Professor of Political Science at Columbia University and co-author of China’s Search for Security.

In all types of political systems, adherents to Liberal Democratic Values (LDV) display a preference for regime characteristics associated with liberal democracy, he writes for The Journal of Democracy:

This is not surprising in itself, as the LDV and regime characteristics batteries are quite similar. But the implications are encouraging for the stability of democratic systems and discouraging for that of authoritarian systems. In democracies, citizens may be dissatisfied with what they have but do not prefer an alternative. In authoritarian regimes, as LDV spread, so does a preference for democratic regime characteristics. RTWT

The Chinese government is fighting a generational fight to surpass our country in economic and technological leadership, but not through legitimate innovation, not through fair, lawful competition, and not by giving their citizens the freedom of thought and speech and creativity that we treasure here in the United States, the CSIS conference heard.

Global commerce now hinges on China’s $14.55 trillion economy, which in turn is governed by an opaque, authoritarian regime tightly coalesced around one man, TIME’s Campbell adds.

*A former board member of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).