“China has built a giant influence and information apparatus,” Joshua Kurlantzick writes in his new book, Beijing’s Global Media Offensive: China’s Uneven Campaign to Influence Asia and the World. While suppressing free media at home, Beijing has upgraded “its ability to penetrate other states with sharp power, like the coercion of other countries’ media, politicians, and universities,” he states, drawing on several case studies—including the United States, where China spends more than any other country on foreign influence operations.

“China has built a giant influence and information apparatus,” Joshua Kurlantzick writes in his new book, Beijing’s Global Media Offensive: China’s Uneven Campaign to Influence Asia and the World. While suppressing free media at home, Beijing has upgraded “its ability to penetrate other states with sharp power, like the coercion of other countries’ media, politicians, and universities,” he states, drawing on several case studies—including the United States, where China spends more than any other country on foreign influence operations.

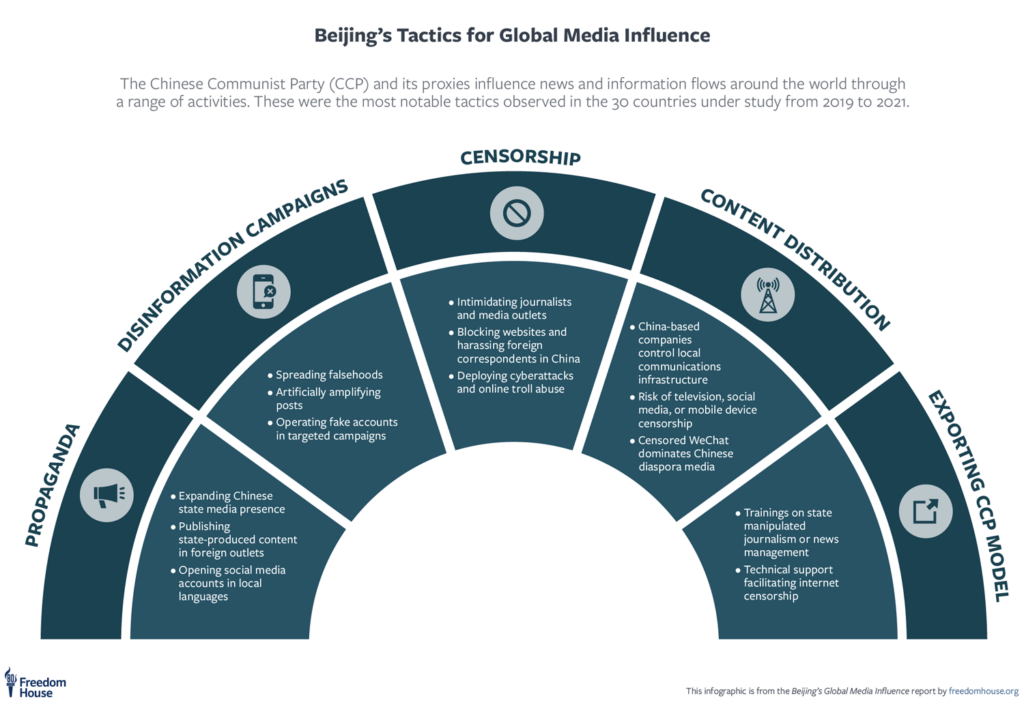

“China increasingly and openly wants to reshape the world in its image,” adds Kurlantzick, a senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations. It aims to become “a global media and information and disinformation superpower,” as he puts it, employing state media, blatant propaganda or less direct means, such as the regime’s Confucius Institutes, to shape news coverage and media narratives to advance its “brand of technology-enabled authoritarianism.”

But its media strategy is not simply designed to promote a “China model,” but part of a broader effort to achieve multiple goals, enhancing the regime’s “discourse power” to shape global narratives, Kurlantzick tells Democracy Digest.

Your new book addresses Beijing’s efforts to project influence through a global media offensive. But, since opinion polls consistently find that China’s image and reputation have largely diminished over recent years, can we deem its media initiatives a failure?

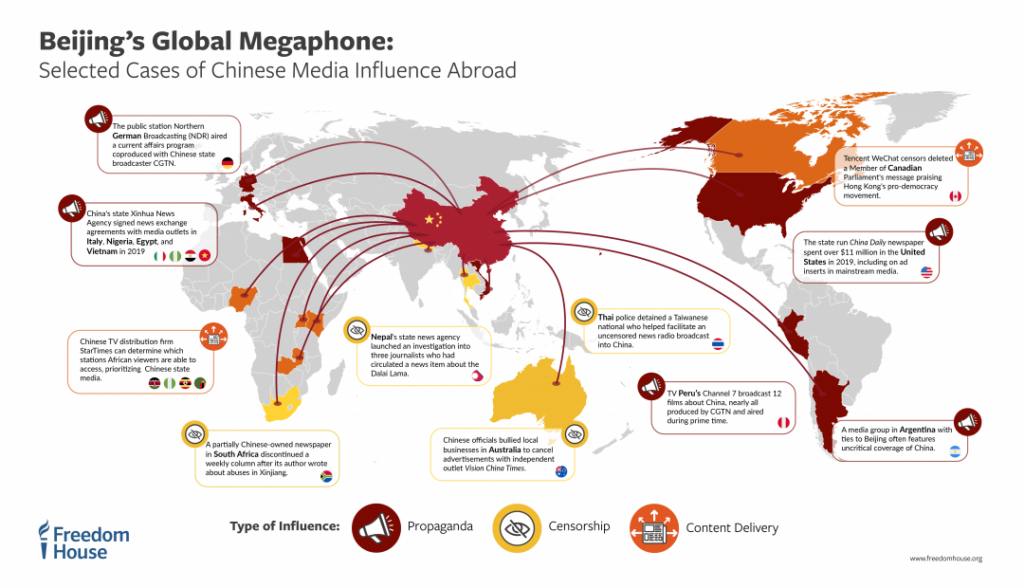

Mostly – but not all, and I talk about media and information. Certainly Xinhua has been a success, and via content-sharing agreements is getting picked up in more and more news outlets, and readers are often not aware they are reading Xinhua content. China has gained control, through proxies, over most of the Chinese-language news outlets in most countries. China has improved its ability to wield disinformation on major social media platforms, and has still been successful in exporting its model of a closed or sovereign internet to many countries, even as its image has declined badly – in part for other reasons than media failures, but rather because of Zero-COVID, Xi’s authoritarianism, overly aggressive diplomacy, support for Putin, etc.

Have China’s investments been worthwhile or wasted? Or are there any states or regions in which they have borne fruit?

Have China’s investments been worthwhile or wasted? Or are there any states or regions in which they have borne fruit?

I think much of China’s media investments have basically been wasted, at least those related to the big state media other than Xinhua. The investments in CGTN, CRI – the hiring of foreign reporters and opening more bureaus and trying to make them seem like real, respectable news outlets – have mostly been wasted. They have gained little audience share (CGTN and CRI) in most countries, which I discuss in the book, and now have lost many of their good reporters, as China becomes more authoritarian and the state media is just very turgid. Xinhua still has that possibility of being seen as a viable news outlet, because it is increasingly signing content sharing deals with other outlets, and then gets amalgamated into the copy of other outlets. This is particularly true in Southeast Asia and Africa and some other developing regions, where Xinhua’s expansion is bearing fruit.

How do China’s investments in CGTN, Xinhua, and other aspects of what Freedom House calls Beijing’s global megaphone, compare relative to other autocratic media investments like Russia’s RT or Qatar’s Al Jazeera in terms of impact or sustainability?

They are nowhere near as effective as RT or Al Jazeera, other than possibly Xinhua, which continues to expand, be brought into the copy of many news outlets around the world, and get normalized as a legit news outlet. China can’t have state outlets like RT, which encourages wild conspiricizing but also, before the Ukraine war, had some degree of freewheeling attitude – CGTN and CRI are just too bland, too turgid to be like RT, to poke at conventional wisdom and create crazy conspiracies because acting like that – you don’t know where it could lead you, and reporters for Chinese state media are terrified of what happens if they put a foot wrong.

Also, China has lost most of the high quality foreign reporters, from African outlets, SE Asian outlets, U.S. and European outlets, that they hired when they were building up CGTN and other outlets, because those reporters don’t want to be tarred now by working for CGTN and CRI, which have been marked out by many leading liberal democracies as state actors and even come under FARA in the United States – and CGTN had its license pulled in the U.K. And re: Al Jazeera, Beijing just hasn’t been willing to let its reporters have the latitude at state media outlets that Qatar lets Al Jazeera reporters have, to do real quality reporting, in areas outside of Qatar and parts of the Middle East – so Chinese outlets can’t get the prestige of Al Jazeera.

How does China’s media strategy vary – if at all – between different states and/or regions?

How does China’s media strategy vary – if at all – between different states and/or regions?

I think China is much more focused on getting Xinhua picked up as legitimate content in major media outlets in many developing countries, where media outlets are really short of cash and Xinhua is often free or very cheap. They are less focused on getting Xinhua picked up in leading liberal democracies, although Xinhua has signed content-sharing deals with some major newswires like AFP and DPA from Germany and some Italian state news outlets.

But a consistent strategy is an attempt to narrow the area available for Chinese language readers and viewers and listeners to access independent Chinese media – this is true virtually everywhere around the globe, in some part by having pro-Beijing owners buy up local media and shift them toward less independent coverage and more pro-Beijing coverage. You can see this now in how the media diet of most countries, in Chinese – there is very little independent coverage, and there are huge numbers of Chinese readers and listeners and viewers in many countries in SE Asia, the Pacific, the U.S, Canada, etc. So that is a common tactic across many countries.

Is the strategy symptomatic of an ideological or geo-political offensive – to promote or export a ‘China Model’ of development or a blueprint for high-tech authoritarianism, as some claim – or largely instrumental – driven by economic interests?

Is the strategy symptomatic of an ideological or geo-political offensive – to promote or export a ‘China Model’ of development or a blueprint for high-tech authoritarianism, as some claim – or largely instrumental – driven by economic interests?

I think the media strategy is part of a broader effort to achieve multiple goals, not just one or the other.

One: To give China a greater say in global narratives, in global “discourse power” about China, about world events, about the CCP, about China-U.S. relations, about China’s economic interests, about a wide range of foreign policies, and many other issues. Xi has been very clear about this, that China lagged in this ability, and needed greater abilities to wield “discourse power.”

Two, in theory, they wanted to create media outlets that would be seen as credible to wield that discourse power, along with their diplomats and other vehicles of discourse power. I think that’s mostly failed, as I said, except with Xinhua – and their recent actions like aggressive diplomacy and support for Putin, and more obvious, one man, ineffective rule, etc – have undermined badly that discourse power.

Three, to promote a China model of managerial, authoritarian capitalism that also includes high-tech methods to control the Internet, to create a walled garden, or “sovereign” internet, a tactic increasingly being exported to other countries. This “sovereign” internet idea remains highly popular with other autocratic regimes and is increasingly being picked up in Russia, the Middle East, parts of Africa, and Southeast Asia. But the idea of China as an effective model of managerial, authoritarian capitalism – which was part of the reason for this media campaign, I think that has largely failed over the last three years.