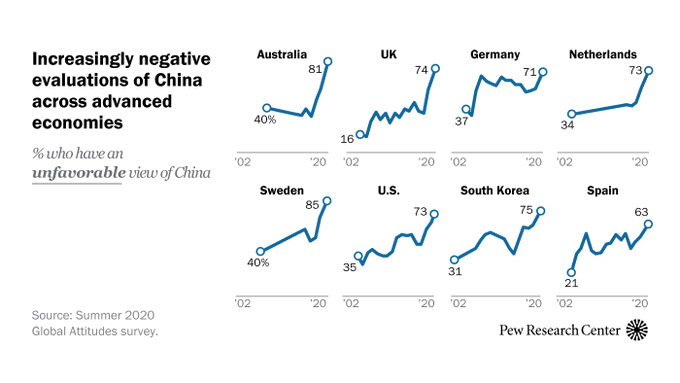

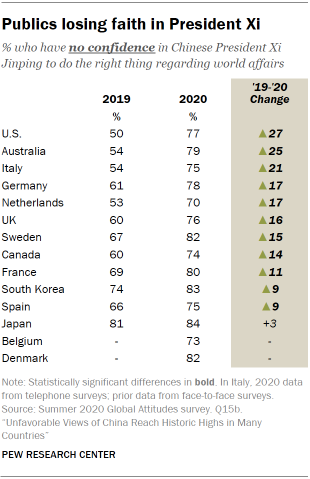

Views of China have grown more negative in recent years across many advanced economies, and unfavorable opinion has soared over the past year, a new 14-country Pew Research Center survey shows. Today, a majority in each of the surveyed countries has an unfavorable opinion of China. And in Australia, the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, the United States, South Korea, Spain and Canada, negative views have reached their highest points since the Center began polling on this topic more than a decade ago.

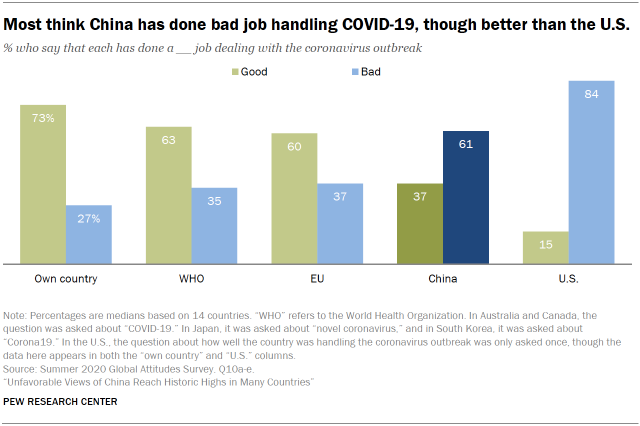

Across the 14 nations surveyed, a median of 61% say China has done a bad job dealing with the outbreak. This is many more than say the same of the way the COVID-19 pandemic was handled by their own country or by international organizations like the World Health Organization or the European Union, Pew adds.

“I think this sentiment is likely to persist because of longer-term trends in China toward growing repression,” said Jessica Chen Weiss, an associate professor of government at Cornell University who studies Chinese foreign policy. “As long as its order of priorities remains in place, it will be difficult for the Chinese Communist Party to really turn around the trends in public opinion overseas,” she told The Times.

No government threatens the international human rights system like China’s ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Suzanne Nossel writes for Foreign Policy. Despite having signed onto certain international agreements, it has never been willing to guarantee rights to free expression, fair trials, religious liberty, or freedom from torture and forced labor. Beijing also rejects the role of human rights watchdogs, including nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and independent journalists.

But the West’s democracies appear reluctant, divided or both in responding to the threat of what the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) calls Beijing’s sharp power.

National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

A high-ranking German official suppressed a sensitive intelligence report in 2018 on China’s growing influence in Germany out of fear it would damage business ties with China, Axios has learned.

The highly sensitive report, completed in 2018, examined the Chinese government’s attempts to influence every level of German government, society and business, according to two former U.S. intelligence officials, notes Axios expert Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian.

“Germany depends on exports to a high degree, and that gives business a large influence. Business representatives talk to the government and are used to being listened to,” said Volker Stanzel, a former German ambassador to China, in an interview with Axios. “The Chinese Communist Party succeeded in globalizing its economy because it was able to join itself to foreign business interests,” said Stanzel.

But things are starting to change in Germany and around Europe amid growing global scrutiny over China’s economic practices and human rights abuses, Allen-Ebrahimian adds. On a recent five-nation tour of Europe, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi was assailed with pointed questions about China’s crackdown in Hong Kong, its mass internment camps, and concerns about Chinese telecom giant Huawei.

“Germany has traditionally viewed China through an economic prism, not a security prism. That has really begun to change this year,” said Noah Barkin, an expert on Europe-China relations at the Rhodium Group. “Germans are coming to the realization that they need to establish red lines, that they need to push China more forcefully, and they need to emphasize human rights.”

“Germany has traditionally viewed China through an economic prism, not a security prism. That has really begun to change this year,” said Noah Barkin, an expert on Europe-China relations at the Rhodium Group. “Germans are coming to the realization that they need to establish red lines, that they need to push China more forcefully, and they need to emphasize human rights.”

While a rising China might want to one day surpass the United States and become the world’s main power and some in China dream of it becoming a benevolent hegemon (wang), instead of an aggressive one (ba), China’s actions over the past few years, combined with the lack of a long-term vision, work to its disadvantage, notes analyst Andreea Brînză.

Over the years, there have been numerous moments when one person was put above China’s long-term interest, showing that China’s foreign policy is driven more by other countries’ actions and its own internal political interests, than by a coherent long-term strategy, she writes for The Diplomat. Let’s just think about the cases of Mongolia and the Dalai Lama, Norway and Liu Xiaobo, Sweden and Gui Minhai, and more recently, although very different, Canada and Meng Wanzhou.

Beijing’s soft power may be headed for a hard landing in Cambodia, observers suggest.

While COVID-19 has helped to improve China’s image, it also constrains China’s ability to help Cambodia transform Sihanoukville into Cambodia’s Shenzhen, due to the economic slowdown that it aggravated in China, according to Jing Jing Luo and Kheang Un. A delay in transforming Sihanoukville into a more diversified economic entity might hurt China’s image, with the Cambodian public thinking that China is merely “talking the talk” but not “walking the walk” in its claim of building a shared future for both countries.

Distrust of China Jumps to New Highs in Democratic Nations https://t.co/lzDPz9evwY

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) October 6, 2020