The world faces the prospect of more tension with China over trade, security and human rights after Xi Jinping, the country’s most powerful leader in decades, awarded himself another term as leader of the ruling Communist Party, AP reports:

Xi has tightened control at home and is trying to use China’s economic heft to increase its influence abroad. Washington accused Beijing this month of trying to undermine U.S. alliances, global security and economic rules. Activists say Xi’s government wants to deflect criticism of abuses by changing the U.N.’s definition of human rights.

Xi says “the world system is broken and China has answers,” said William Callahan of the London School of Economics. “More and more, Xi Jinping is talking about the Chinese style as a universal model of the world order, which goes back to a Cold War kind of conflict.”

Former Chinese President Hu Jintao was unexpectedly escorted out of Saturday’s closing ceremony the ruling Communist Party’s Congress, CBC News reports (above).

The CCP’s Twentieth National Congress is clearly a turning point, says Guoguong Wu, a senior research scholar at Stanford University’s Center on China’s Economy and Institutions. With it, Xi has turned the Party’s post-Mao oligarchic dictatorship into a neo-totalitarian tyranny with himself as the “core.” But the change will be felt more broadly and deeply than a critical shift at the top of elite Chinese politics. The PRC that puts the economy first is no more, and it is a harbinger of greater changes to come, he writes for the Journal of Democracy.

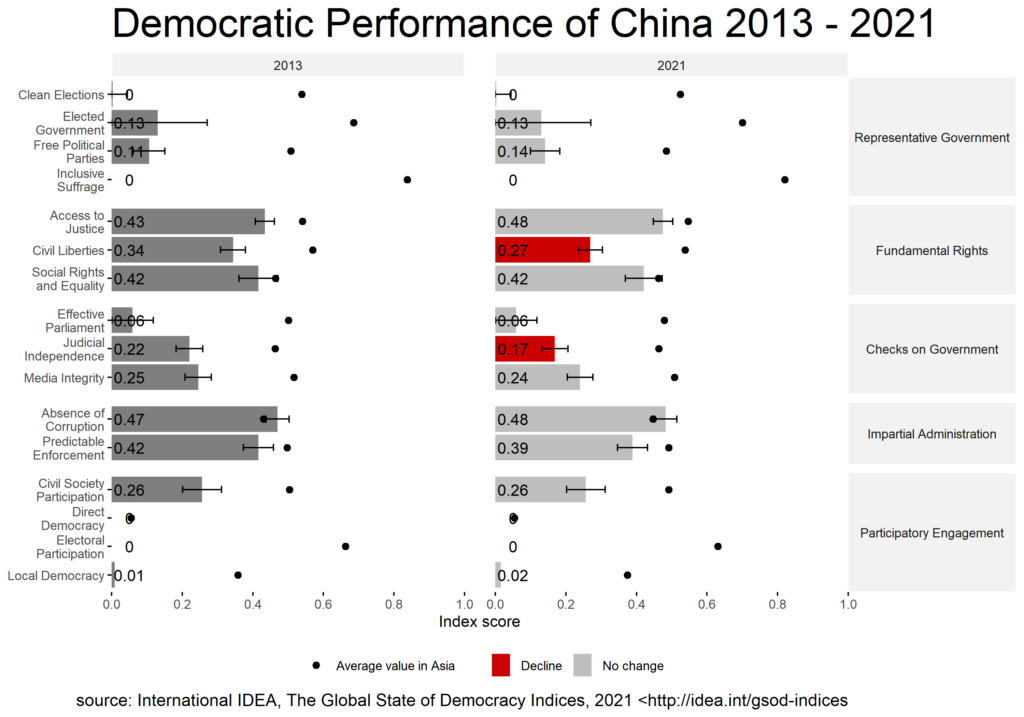

China’s scores in the Global State of Democracy Indices have reflected Xi’s increasing authoritarianism, with no improvements in any subattribute since 2013 and negative trends manifesting especially in Civil Liberties and Judicial Independence, adds International IDEA’s Alberto Fernandez Gibaja.

Through centralization, Xi has replaced the CCP with his own control-obsessed version, but at the cost of undermining the operating principles that have played an important role in the party’s longevity and success so far, notes Lecturer in Chinese Society at King’s College London. It remains to be seen whether this new “XiCP” will be as successful in securing the prosperity of a dynamically changing society as the party we knew up until recently, he writes for the Conversation.

Prior to the CCP Congress, police quickly stopped a one-person protest on Sitong Bridge. But this rare protest inspired further actions on social media and in multiple locations around the world, adds analyst Chauncey Jung. With hashtags such as #Notmypresident, #endxictatorship, and #FreeChina, internet users demonstrated their anger and disapproval of the Chinese regime and Xi Jinping’s ambition to rule the country for a third term – or even for life, he writes for the Diplomat:

Days after the Poster Campaign – similar to the Great Translation Movement, which began after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – some individuals started to take the initiative to share tips on organizing in-person rallies and events in major cities around the world. However, it will take further actions to have concrete impacts against the Chinese regime. In addition to organizing protests and demonstrations, activities such as lobbying and direct political participation should also be considered and prioritized to push for democracy and freedom in China.

Minxin Pei

While trampling institutional rules and norms may benefit autocratic rulers, it is not necessarily good for their regimes, notes Claremont McKenna professor Minxin Pei, a National Endowment for Democracy (NED) board member. The CCP’s experience under Mao is a case in point. Unencumbered by any institutional constraints, Mao engaged in ceaseless purges and led the party from one disaster to another, leaving behind a regime that was ideologically exhausted and economically bankrupt.

Deng understood that a rules-based system was essential to avoid repeating that disastrous experience, Pei observes. But his conviction could not overcome his self-interest, and the institutional edifice he built in the 1980s turned out to be little more than a house of cards. Mr. Xi’s confirmation this month is merely the breeze triggering its inevitable collapse.

Xi’s “Zero COVID” policy, which tracks individuals using smartphone apps and has confined tens of millions to their homes, “is indicative of how Xi Jinping wants Chinese society to work,” said the LSE’s Callahan. “It is to be under constant surveillance and control,” he said. “It has become much more authoritarian and at times totalitarian.”

The new U.S. National Security Strategy projects a vision rooted in individual liberty, democratic governance and the rule of law, but it is hard to reconcile with China’s authoritarian objectives, Hudson Institute analyst Nadia Schadlow writes for the Wall Street Journal.

The CCP seeks nothing less than the reprogramming of society in a real-life, tech-fueled dystopia, notes Journal of Democracy editor Will Dobson. In their deeply valuable book, Surveillance State: Inside China’s Quest to Launch a New Era of Social Control, veteran Wall Street Journal reporters Josh Chin and Liza Lin detail in chilling fashion how China has traded old-style, shoe-leather surveillance tools for Silicon Valley sophistication, he writes:

The CCP seeks nothing less than the reprogramming of society in a real-life, tech-fueled dystopia, notes Journal of Democracy editor Will Dobson. In their deeply valuable book, Surveillance State: Inside China’s Quest to Launch a New Era of Social Control, veteran Wall Street Journal reporters Josh Chin and Liza Lin detail in chilling fashion how China has traded old-style, shoe-leather surveillance tools for Silicon Valley sophistication, he writes:

China’s citizens are effectively imprisoned inside an algorithmic bubble. In this vision, no more does the Party need to content itself with chasing dissidents before they inspire thousands or go to ground. Rather the goal is to harness the power of big data to predict and identify those people most likely to pose a threat to the Party—before they act. China’s people are reduced to “a digital lineup of more than a billion people,” and the whole of human society exists as a massive engineering problem where behavior can be “standardized.”