Facebook is working on building a war room (both in the physical sense and in the staffing sense) to protect elections, POLITICO reports.

More than 300 people across the company are working on the initiative, but the War Room will house a smaller team of about 20 people focused on rooting out disinformation, monitoring false news and deleting fake accounts that may be trying to influence voters before coming elections in the United States, Brazil and other countries, according to The New York Times’ Sheera Frenkel and Mike Isaac.

What “happens in the War Room will be a ‘last line of defense’ for Facebook engineers to quickly spot unforeseen problems on and near Election Days in different countries,” said Samidh Chakrabarti, who leads Facebook’s elections and civic engagement team. “Many of the company’s other measures are meant to stop disinformation and other problems long before they show up in the War Room.”

What “happens in the War Room will be a ‘last line of defense’ for Facebook engineers to quickly spot unforeseen problems on and near Election Days in different countries,” said Samidh Chakrabarti, who leads Facebook’s elections and civic engagement team. “Many of the company’s other measures are meant to stop disinformation and other problems long before they show up in the War Room.”

This week, the Russian Defense Ministry tried to discredit the official findings that a Russian missile downed a Malaysian Air flight (MH17) in Ukraine in July 2014, killing 298 people, say two leading analysts.

This week, the Russian Defense Ministry tried to discredit the official findings that a Russian missile downed a Malaysian Air flight (MH17) in Ukraine in July 2014, killing 298 people, say two leading analysts.

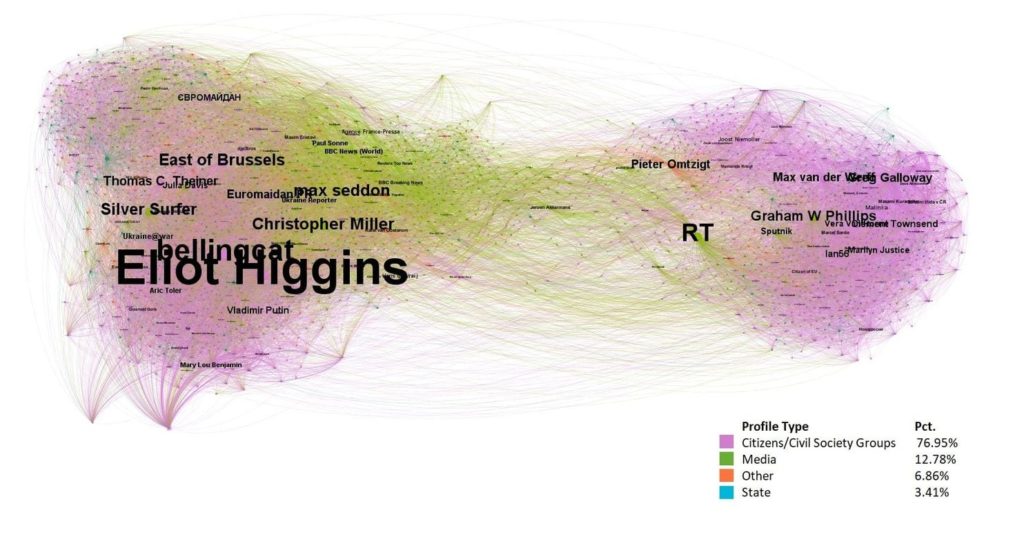

We know some of the top-down regime tactics and strategies, but far less about who actually spreads digital disinformation and who counters it. To understand who spreads disinformation on social media, we looked at the MH17 debate on Twitter (above), note University of Copenhagen and Digital Disinformation analysts Yevgeniy Golovchenko and Rebecca Adler-Nissen.

In our research (with Mareike Hartmann), just published in International Affairs, we find that citizens and civil society groups play a crucial role in both spreading and combating online disinformation. In fact, citizens outperform both mainstream media and state actors in some cases, they write for The Washington Post:

In our research (with Mareike Hartmann), just published in International Affairs, we find that citizens and civil society groups play a crucial role in both spreading and combating online disinformation. In fact, citizens outperform both mainstream media and state actors in some cases, they write for The Washington Post:

It’s easy to think that the Kremlin and Western authorities generate strategic campaigns to “weaponize” information to win over local and global public opinion. But this view reduces citizens and civil society to mere targets, to be manipulated for military or strategic goals. In the digital age, social media enables ordinary citizens to do more than passively receive news — they are also as active and influential in opposing disinformation as they are in spreading it. Any efforts to fight digital disinformation thus may find it useful to mobilize the resources of engaged citizens and civil society.

In an era of increasing technological, cultural and geo-political change, the rise of disinformation undermines the institutions that nations rely on to function and creates risks across society. At the heart of the challenge is the battle of truth and trust, argues Atlantic Council analyst John Watts.

In an era of increasing technological, cultural and geo-political change, the rise of disinformation undermines the institutions that nations rely on to function and creates risks across society. At the heart of the challenge is the battle of truth and trust, argues Atlantic Council analyst John Watts.

Technology has democratized the ability for sub-state groups and individuals to broadcast a narrative with limited resources and virtually unlimited scope, he writes in a new report, “Whose Truth: Sovereignty, Disinformation and Winning the Battle of Trust”:

Incidents can be broadcast around the world in real time from smart phones, while their appearance of being live and on-the-ground give them a veneer of authenticity. Yet they can be selective in what they show, lack context, and even be edited to mislead. This has resulted in the rise of battling videos where opposing groups seek to release additional “authentic” footage to provide greater context and counter the narrative. Meanwhile, those seeking to amplify a message carefully select the “facts” that suit their own agenda, and few seek further validation of authenticity.

Incidents can be broadcast around the world in real time from smart phones, while their appearance of being live and on-the-ground give them a veneer of authenticity. Yet they can be selective in what they show, lack context, and even be edited to mislead. This has resulted in the rise of battling videos where opposing groups seek to release additional “authentic” footage to provide greater context and counter the narrative. Meanwhile, those seeking to amplify a message carefully select the “facts” that suit their own agenda, and few seek further validation of authenticity.

The democratization of technology has given individuals capabilities on par with corporations, and has given corporations capabilities previously within the purview of states. States, meanwhile, now have capabilities that we do not yet fully understand and which lack properly defined limitations, restraints, and international norms, he adds:

The democratization of technology has given individuals capabilities on par with corporations, and has given corporations capabilities previously within the purview of states. States, meanwhile, now have capabilities that we do not yet fully understand and which lack properly defined limitations, restraints, and international norms, he adds:

For a rules-based order to function, there must be trust that each individual will be treated fairly and equally, and that those who fail to adhere to the community’s standards will be punished. This is true for all forms of government as even the most oppressive must ultimately respond to the desires of its populace if it is to be sustainable. But it is particularly true in democratic ones and is true at every level: from a small financial transaction through to the peaceful transfer of political power from one government to another. Where this trust breaks down— through government corruption, persecution of minorities, or the failing of key institutions—societies cease to function effectively. RTWT

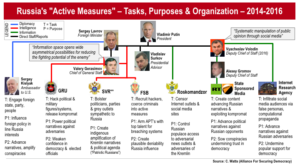

Russia’s Internet Research Agency directed social media disinformation interference in the US Presidential Election, according to a must-read analysis in The New York Times.

Russia’s Internet Research Agency directed social media disinformation interference in the US Presidential Election, according to a must-read analysis in The New York Times.

How prepared was the intelligence community in the summer of 2016 to identify Moscow’s hacking and disinformation campaigns? The Washington Post asks Greg Miller, author of a new a narrative history of Moscow’s interference.

“I think they were fairly well-equipped and positioned to see hacking operations, and there’s lots of evidence that they did detect the hacking itself. In a weird way, this is not unlike 9/11,” he suggests:

Clint Watts/Alliance for Securing Democracy

Obviously not in terms of the devastation and bodies lost, but in the failure of intelligence analysts and experts to imagine the potential of a threat, to imagine the full magnitude of a foreign threat. That was clear here — the inability to see how something like this could be weaponized. Not only taking stolen material and dumping it online, but doing it at a moment to achieve maximum impact in the middle of an American election as part of an active measure operation, augmented by an entire Russia social-media campaign.