Social media firms should establish “specialized Russian-focused teams” staffed with experts in Russian language, culture, and internet practices, according to a new report.

“Combating Russian Disinformation: The Case for Stepping Up the Fight Online,” from New York University’s Center for Business and Human Rights, has a series of sensible recommendations for internet platform companies and governments around the world with defenses that would meddle with the Russian meddlers without impinging on civil liberties, writes Peter Coy, the economics editor for Bloomberg Businessweek.

By targeting Russia, companies can “signal externally and internally that Russian disinformation, because it is part of a broader Kremlin agenda to destabilize democracy, is more pernicious than other forms of ‘fake news,’” the report adds. RTWT

By targeting Russia, companies can “signal externally and internally that Russian disinformation, because it is part of a broader Kremlin agenda to destabilize democracy, is more pernicious than other forms of ‘fake news,’” the report adds. RTWT

Americans associate misinformation with Facebook and the ways it shaped debate around the 2016 presidential election. But in other countries, falsities are just as likely to spread on private messaging services — sometimes with deadly consequences, the Washington Post reports:

At least two dozen people have been killed in mob lynchings in India since the start of the year, their deaths fueled by rumors that spread on WhatsApp, the Facebook-owned messaging service…..Messaging platforms have hosted disinformation campaigns in at least 10 countries this year, according to a report by the Computational Propaganda Project at Oxford University.

“In the U.S., the disinformation debate is about the Facebook news feed, but globally, it’s all about closed messaging apps,” said Claire Wardle, executive director of First Draft, a nonprofit news literacy and fact-checking organization affiliated with Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

Closed platforms

“In many countries, messaging services are the main platform to get online,” said Samantha Bradshaw, co-author of the report from the Computational Propaganda Project. “The closed platforms can be more dangerous because the information is spreading in these intimate groups of friends and family — people we tend to trust.”

“In many countries, messaging services are the main platform to get online,” said Samantha Bradshaw, co-author of the report from the Computational Propaganda Project. “The closed platforms can be more dangerous because the information is spreading in these intimate groups of friends and family — people we tend to trust.”

Russian propaganda operations are also expanding in Latin America, where the objective is not to convince audiences as to the merits of Russian policy, to boost the image of Russia, or to promote a Russian world view, but rather to erode confidence in western institutions such as democracy and free trade, as well as western-dominated sources of information, notes Brian Fonseca, an Adjunct Professor at FIU’s Department of Politics and International Relations and a Cybersecurity Policy Fellow at the Washington D.C.-think tank New America:

In today’s information space, the responsibility of finding truth has shifted from media outlets to individuals, and this is complicating individuals’ ability to sift through the oversaturated media environment to find truth. According to the National Endowment for Democracy, propaganda is used by Moscow to pursue its “foreign policy goals through a ‘4D’ offensive: dismiss an opponent’s claims or allegations, distort events to serve political purposes, distract from one’s own activities, and dismay those who might otherwise oppose one’s goals.”

In today’s information space, the responsibility of finding truth has shifted from media outlets to individuals, and this is complicating individuals’ ability to sift through the oversaturated media environment to find truth. According to the National Endowment for Democracy, propaganda is used by Moscow to pursue its “foreign policy goals through a ‘4D’ offensive: dismiss an opponent’s claims or allegations, distort events to serve political purposes, distract from one’s own activities, and dismay those who might otherwise oppose one’s goals.”

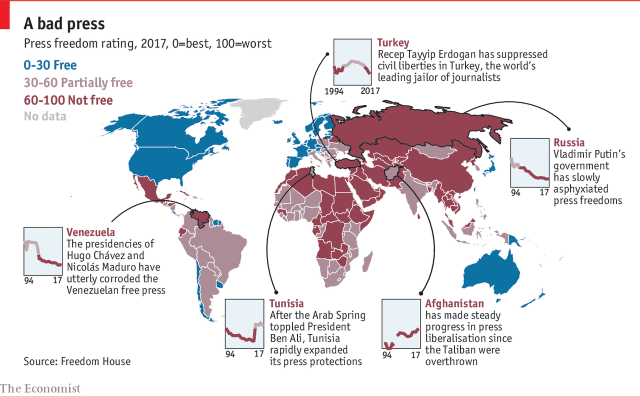

Fake news is a factor in the atrophying of media freedom across the world, The Economist adds:

According to scores compiled by Freedom House, a think-tank, the muzzling of journalists and independent news media is at its worst point in 13 years. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, the number of journalists jailed for their work is at the highest level since the 1990s. The deterioration has come from all quarters: Vladimir Putin has so thoroughly throttled the Russian media that Freedom House’s scorers rated Venezuela freer. Newer strongmen, such as Daniel Ortega, Nicaragua’s blood-soaked president, and Viktor Orban, Hungary’s illiberal prime minister, have also flexed censorious muscles.

Russian cyber-attacks, information warfare, or political meddling are far more pernicious than kinetic warfare, says CEPA’s Edward Lucas:

Russian cyber-attacks, information warfare, or political meddling are far more pernicious than kinetic warfare, says CEPA’s Edward Lucas:

Dealing with these threats requires an upheaval in government and society, rethinking our silo-based approach to counter-intelligence, criminal justice, financial supervision, internet security, and media regulation, while refashioning our threadbare security culture. This process will be costly and difficult, with some painful trade-offs. American leadership would be welcome. But we can manage without.

Combating disinformation and defending digital democracy were prominent themes at RightsCon Toronto, where more than 2,500 attendees generated a number of coalitions, projects, launches, declarations, and announcements, including the Toronto Declaration on AI, or Access Now’s report on FinFisher surveillance malware).

Combating disinformation and defending digital democracy were prominent themes at RightsCon Toronto, where more than 2,500 attendees generated a number of coalitions, projects, launches, declarations, and announcements, including the Toronto Declaration on AI, or Access Now’s report on FinFisher surveillance malware).

A major international conference on human rights and technology in Australia will address the implications of emerging technology for Internet freedoms, democracy and free speech, notes Brett Solomon, Executive Director of Access Now, which has been active on several fronts:

- In Geneva, Switzerland, the group fought to save the U.N. “Internet Resolution” from the sharks circling lead to a number of wins, and losses — from concessions that resulted in language which comes close to threatening (instead of promoting respect for) the rights of people using the internet, to the acknowledgement of encryption and anonymity, improved language on internet shutdowns, and more.

In Cambodia, it noted a new directive aimed at combating “fake news” which will reportedly, among other restrictions, require all websites to register with Cambodia’s Ministry of Information or face additional scrutiny – effectively curbing free speech in the name of “fake news.”

In Cambodia, it noted a new directive aimed at combating “fake news” which will reportedly, among other restrictions, require all websites to register with Cambodia’s Ministry of Information or face additional scrutiny – effectively curbing free speech in the name of “fake news.”- In Ethiopia, it verified the unblocking of websites which were a part of a wave of positive reforms, including the rapid expansion of internet freedom and digital rights, which have swept the country.

- In India, Access Now joined the #SaveOurPrivacy project, an Indian advocacy movement founded in support of a model draft law called the Indian Privacy Code, 2018.

- In Egypt, along with the Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression (AFTE), it condemned the Law on Combating Cybercrimes (“Cybercrime Law”).

- And around the world, Access Now has been fighting censorship during the 2018 elections season – from social media disruptions in Mali to the blocking of opposition websites in Pakistan and more.