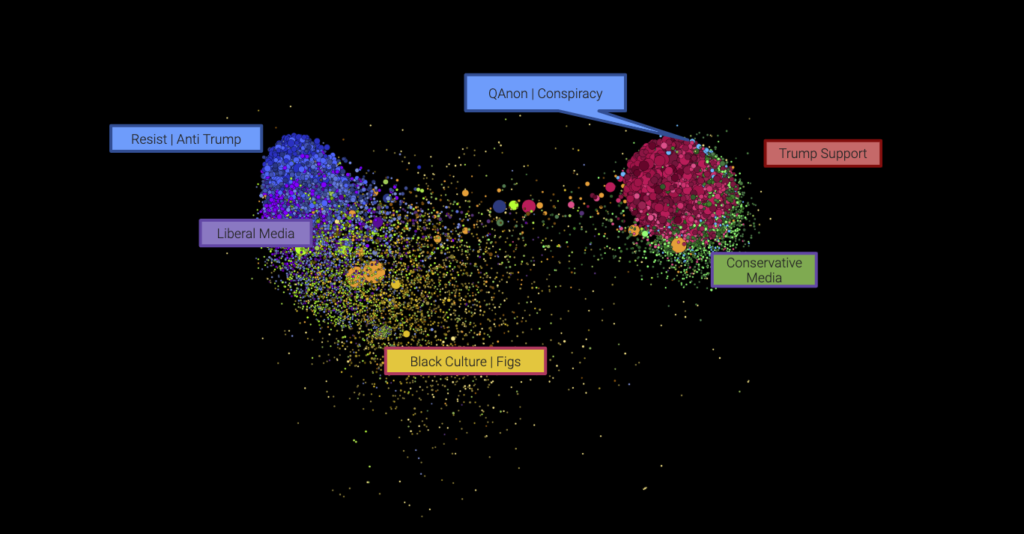

Graphika

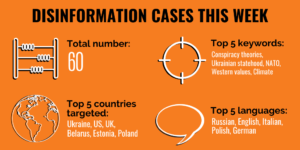

A Russian-linked operation aimed at dividing Western allies spread disinformation on social media for three years, according to a new analysis, Bloomberg reports:

Hundreds of accounts on multiple internet platforms amplified 44 narratives in at least six languages over the course of the effort, which targeted relationships between the U.S. and U.K, as well as the U.S. and Germany, among other Western allies, according to a report released Tuesday by Graphika, a company that uses artificial intelligence to map and analyze information on social media.

The disinformation effort ran from October 2016 to October 2019 and was part of a broader, Russian-based operation known as “Secondary Infektion,” according to Graphika. Facebook Inc. and Reddit have previously removed accounts related to the operation.

One of the outlets that ran with the story, Begemot (“hippopotamus” in Russian), is “full-fledged Kremlin media,” said Marcel H. Van Herpen, director of the pro-European Union Cicero Foundation and the author of several books about propaganda and modern Russia, including Putin’s Propaganda Machine.

One of the outlets that ran with the story, Begemot (“hippopotamus” in Russian), is “full-fledged Kremlin media,” said Marcel H. Van Herpen, director of the pro-European Union Cicero Foundation and the author of several books about propaganda and modern Russia, including Putin’s Propaganda Machine.

Experts say a recent trial in Italy, featuring the inclusion of two videos from Russia Today, plus a report on the website Russkaya Vesna that the Ukrainian government said was false, raised questions about the extent to which fake news, after infiltrating the West’s news media and elections, is now penetrating its courts, The New York Times reports.

“Contamination is by its nature expansive,” said Luciano Floridi, a professor of philosophy and the ethics of information at Oxford who has studied the effects of disinformation. And it can easily spread from media and politics to the judiciary, he added.

Taiwan is ramping up efforts ahead of a Jan. 11 election to combat fake news and disinformation that the government says China is bombarding the island with to undermine its democracy, Reuters reports:

Taiwan, which holds presidential and legislative elections on Jan. 11, says it is particularly vulnerable to influence-peddling by its giant, autocratic neighbor China, which claims Taiwan as its own territory, to be brought under Beijing’s rule by force if need be.

Taiwan, which holds presidential and legislative elections on Jan. 11, says it is particularly vulnerable to influence-peddling by its giant, autocratic neighbor China, which claims Taiwan as its own territory, to be brought under Beijing’s rule by force if need be.

“Taiwan is a democratic, open society. They are using our freedom and openness, bringing in news that is not beneficial to the government,” Chiu Chui-cheng, deputy head of Taiwan’s Mainland Affairs Council, told Reuters, referring to China. “They are seeking to confuse the perception of people. It’s a perception war,” he said. “Mainland China uses organizations in Taiwan to help disseminate fake news.”

Conspiracy theories are used as counter-narratives to confuse the actual nature of events and, in doing so, push a particular ideological view of the world, notes Senior Lecturer in Applied Linguistics at the UK’s Open University:

Conspiracy theories are used as counter-narratives to confuse the actual nature of events and, in doing so, push a particular ideological view of the world, notes Senior Lecturer in Applied Linguistics at the UK’s Open University:

It’s worth noting that all explanations operate as a type of narrative. A basic dramatic narrative has three steps to it: (1) a person embarks upon a (2) journey into a hostile environment which (3) ultimately leads to self-knowledge. This same basic structure applies to explanations: (1) you want to discover some information; (2) you find a way of discovering it; and (3) your world is changed as a result.

But, as recent research I’ve been doing shows, there are several ways in which conspiracy theories draw directly on elements of storytelling that are found in fiction rather than factual narratives, he writes for The Conversation.

A new initiative aimed at countering the influence operations of authoritarian regimes was announced today.

The goal of 21Democracy is to highlight the risks for consumer choice, privacy, human rights, national security, and intellectual property in the light of rising authoritarianism across the globe, the Consumer Choice Center reports.

The goal of 21Democracy is to highlight the risks for consumer choice, privacy, human rights, national security, and intellectual property in the light of rising authoritarianism across the globe, the Consumer Choice Center reports.

“The narrative of authoritarian regimes unduly influencing consumers and policies in liberal democracies is ongoing and we must be persistent in opposing it where possible,” said Yaël Ossowski, deputy director of the D.C.-based Center. “Whether it’s the actions of Putin’s Russia or the Chinese Communist Party, we cannot compromise the underpinnings of our liberal democratic systems in the face of authoritarian regimes.”

While governments and other institutions are making adaptations in the areas of strategic communications and public diplomacy, they can also adapt to disinformation by providing resources to independent media and civil society pursuing these and other innovative means of reaching and informing audiences, adds Dean Jackson, program officer for research & conferences at the National Endowment for Democracy’s International Forum for Democratic Studies:

While governments and other institutions are making adaptations in the areas of strategic communications and public diplomacy, they can also adapt to disinformation by providing resources to independent media and civil society pursuing these and other innovative means of reaching and informing audiences, adds Dean Jackson, program officer for research & conferences at the National Endowment for Democracy’s International Forum for Democratic Studies:

They can also explore ways to fortify independent media against the tempestuous environment for media sustainability, including capacity-building partnerships for disinformation-focused efforts, more long-term fellowships for investigative journalists, and increased public support for local news media. It is crucial that support for these efforts come in ways that do not

undermine their greatest source of value: independence from political interests. What these adaptations have in common is that none of them are compelling “solutions to disinformation.”

Disinformation, like lying, is not a problem to be solved; it is a tactic that succeeds or fails depending on the circumstances in which it is used, he writes in the latest issue of Public Diplomacy Magazine. Until there are major changes to the environment for news media and political communications, disinformation will continue to be effective.

While Russian interference is well known, American and European institutions are facing greater pressure from the Chinese Communist Party as well, especially surrounding sensitive issues like the Hong Kong protests and the detention of Muslims in Xinjiang, note analysts Nathan Kohlenberg and Thomas Morley.

While Russian interference is well known, American and European institutions are facing greater pressure from the Chinese Communist Party as well, especially surrounding sensitive issues like the Hong Kong protests and the detention of Muslims in Xinjiang, note analysts Nathan Kohlenberg and Thomas Morley.

To respond to this challenge, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, establishes a Social Media Data and Threat Analysis Center under the Director of National Intelligence, they write for the Alliance for Securing Democracy:

The Center will be responsible for coordinating the government-industry partnership that will be required to take on these operations in a comprehensive way. Archiving, analyzing, and, when possible, publishing reports on these influence operations has so far proved to be one of the most effective approaches to hardening American networks and communities against them. By bringing together the perspective that social media companies have on their own networks and users and the threat information possessed by the government, the Threat Analysis Center will provide a mechanism for quickly identifying and disrupting malicious behavior.

In recent years, Slovakia has been referred to as “a pro-European island” in the Visegrad Four, a country whose democracy is stable and whose Euro-optimism remains strong, in particular against the background of recent developments in neighbouring countries, notes the #DemocraCE project‘s Aliaksei Kazharski, a Researcher at the Institute of European Studies and International Relations of the Comenius University in Bratislava and a lecturer at the Department of Security Studies of Prague’s Charles University.

In recent years, Slovakia has been referred to as “a pro-European island” in the Visegrad Four, a country whose democracy is stable and whose Euro-optimism remains strong, in particular against the background of recent developments in neighbouring countries, notes the #DemocraCE project‘s Aliaksei Kazharski, a Researcher at the Institute of European Studies and International Relations of the Comenius University in Bratislava and a lecturer at the Department of Security Studies of Prague’s Charles University.

But some Slovak cultural and educational institutions legitimize and promote pro-Kremlin narratives. Free speech risks being undermined by an anti-Western counter-culture anchored in the political and intellectual environments of Slovakia, he writes for Visegrad Insight.

From observing Russian attempts to spread influence across Europe we learned that the Kremlin uses a pragmatic or “trans-ideological” approach, opportunistically seeking out partners among both the radical left and the radical right, Kazharski adds. The narratives it chooses to promote thus depend on the context and can very well contradict each other.