President Muhammadu Buhari won the last three presidential elections but he was “rigged out of victory,” according to a former US Ambassador.

President Muhammadu Buhari won the last three presidential elections but he was “rigged out of victory,” according to a former US Ambassador.

”I arrived at that conclusion by talking to people who were intimately connected with the entire process,” including both local and foreign-based NGOs, said Council on Foreign Relations analyst John Campbell.

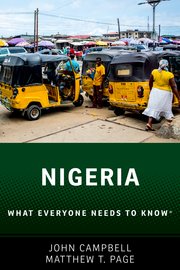

“I think the rigging took place not so much at the polling units but at the places where the results from the polling units were brought together,” said Campbell, co-author of the recently released book Nigeria: What Everyone Needs to Know.

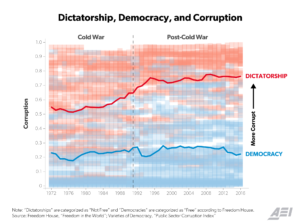

Nigeria is a nation characterized by a type of corruption in which government or public officials seek personal gain at the expense of the led, Campbell and Chatham House analyst Matthew T. Page write.

“Kleptocracy and government dishonesty have corrosive effects on popular confidence in governance,” they add. “Official and unofficial corruption undermine the democratic trajectory and risks overwhelming it. It is among the most important hindrances to the country’s economic and social development.”

“Kleptocracy and government dishonesty have corrosive effects on popular confidence in governance,” they add. “Official and unofficial corruption undermine the democratic trajectory and risks overwhelming it. It is among the most important hindrances to the country’s economic and social development.”

Regulators have long accused the world’s biggest banks of helping manage the illicit fortune amassed by former dictator Sani Abacha, who ruled Nigeria from 1993 until his death, reports suggest:

In 2001, a UK financial watchdog said 15 lenders showed “significant control weaknesses” in handling $1.3bn linked to him and his associates. In 2014, the US Department of Justice froze more than $458m in funds allegedly generated through corruption hidden in bank accounts – including at HSBC, Citigroup and Deutsche Bank – in what it described as the “largest kleptocracy forfeiture action” in its history.

Nigerian politics if left unchecked would be in danger of being infiltrated by criminals, according to political economist and management expert, Prof. Patrick Utomi.

Government is suffocating initiative and too many officials are mediocre, he told a High Level Public-Private Sector Forum in Abuja on the theme of “Democracy that Delivers,” hosted by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), the International Republican Institute (IRI), the National Democratic Institute (NDI), the Centre for International Private Enterprise (CIPE), and Solidarity Centre, which was themed “Democracy that Delivers”.

Government is suffocating initiative and too many officials are mediocre, he told a High Level Public-Private Sector Forum in Abuja on the theme of “Democracy that Delivers,” hosted by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), the International Republican Institute (IRI), the National Democratic Institute (NDI), the Centre for International Private Enterprise (CIPE), and Solidarity Centre, which was themed “Democracy that Delivers”.

Nigeria needs to do more to promote rule of law,” said NED program officer Christopher O’Connor.

“We are inspiring political inclusion leading up to 2019. We also have to build linkages between civil society organizations, the government, public and private sectors, and labor to advance democracy and free, fair, and credible elections,” he added.

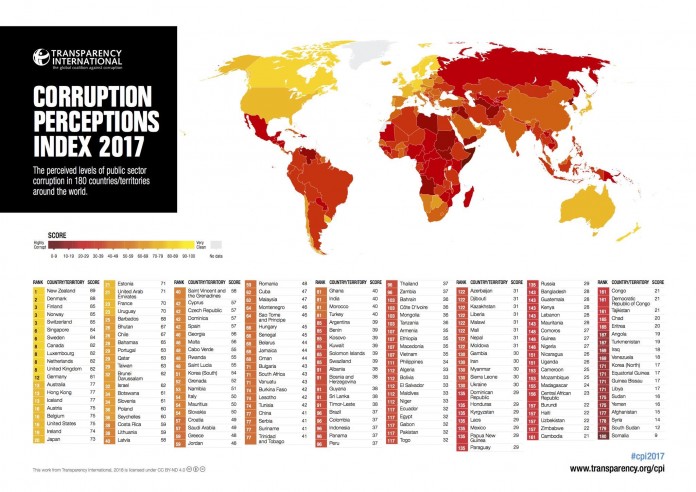

Nigeria consistently scores near the top of an annual “Corruption Perception Index” put together by the watchdog group Transparency International, NPR adds. And Oluseun Onigbinde — the founder of a Nigerian nonprofit that tracks his government’s spending — considers corruption “an existential threat” to his country. Nigeria, says Onigbinde, “has a huge treasure chest of oil wealth. And yet we have some of the worst socioeconomic indicators – things like maternal mortality rates – in the world.”

Nigeria consistently scores near the top of an annual “Corruption Perception Index” put together by the watchdog group Transparency International, NPR adds. And Oluseun Onigbinde — the founder of a Nigerian nonprofit that tracks his government’s spending — considers corruption “an existential threat” to his country. Nigeria, says Onigbinde, “has a huge treasure chest of oil wealth. And yet we have some of the worst socioeconomic indicators – things like maternal mortality rates – in the world.”

Nigerian governance is determined by bargains between the country’s competing but cooperating elites. Presidential politics in Nigeria occur in the context of two political parties, one “slightly to the left,” the other “slightly to the right,” notes CFR’s Campbell :

At present the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) is “slightly to the left” and the All Progressives Congress (APC) is “slightly to the right,” and is the party of incumbent President Muhammadu Buhari. By law and custom the parties may not be based on ethnicity or religion, which are perhaps the two issues of greatest importance to ordinary Nigerians, severely limiting the parties’ relevance to the general public. Instead, the two parties are essentially elite machines for winning elections rather than advancing a policy agenda, and politicians move easily from one to the other depending on personal expediency.