It’s often forgotten that Iran’s Green protest movement of 2009 was the precursor to the so-called “Arab Spring,” an observer notes.

Protest activity and strikes in Iran will likely increase from November 15 to 17, according to the Critical Threats Project (CTP). Organizers have reiterated calls for protests and countrywide strikes on these days and also urged citizens to not pay their utility bills, it reports:

Social media accounts published videos on November 14 claiming to depict protesters traveling from Tabriz, East Azerbaijan to Tehran to demonstrate and “conquer” Tehran.[ii] Other protesters have used similar rhetoric in recent days, calling for citizens to conquer a main Tehran highway during the upcoming protests, as CTP previously reported.[iii]

“World solidarity with the Iranian people right now is of the utmost importance,” said Ladan Boroumand, a historian and the cofounder of the Abdorrahman Boroumand Center for Human Rights in Iran, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). “Girls are down there. They are putting their lives at stake. They are fighting for their own life, for hope, for democracy in Iran.”

credit: Critical Threats Pr

The scenes of widespread domestic unrest are familiar to Ray Takeyh, Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, who lived through the Iranian Revolution. Six factors are working against the regime that bear similarity to the 1978-79 Revolution and have the potential to produce lasting change today, he told Duke’s American Grand Strategy program:

- First, the rhetoric around the protest movements is of abolishment of the Islamic Republic, not of reform.

- Second, a sharp severance exists between the political priorities of the state and the wider society.

- Third, there is newfound division among the elite in society, with even the conservative elite appearing to hedge between the regime’s and protestors’ stances.

- Fourth, different social classes are showing solidarity with each other’s grievances against the government, with work strikes and popular protests combining to strip the regime of its traditional narrative that they exist for and represent the oppressed.

- Fifth, Tehran is reluctant to violently suppress the young women who are the primary torchbearers of these protests (although their restraint is only relative, as security forces have killed an estimated 200 protestors).

- Finally, it does not appear that Iranian society widely accepts the government’s claim of interference and provocation by the typical scapegoats: USA, Israel, and Saudi Arabia.

Credit: defendlawyers

Brave activists seeking a more democratic future for their countries and respect for human rights are deserving of our support, say Freedom House President Michael Abramowitz, the Bush Institute’s David Kramer and Damon Wilson, President & CEO of the National Endowment for Democracy. A handful of them will be coming to Dallas this week to speak at “The Struggle for Freedom” conference.

The desire to live free from oppression is universal; no country, no people are doomed to live under strongmen forever, they write for the Dallas Morning News. But sometimes the people in these countries need a boost — moral, political, even financial. That’s where the United States comes in, together with our democratic friends and allies.

The Iranian protests have not become a revolution yet, adds analyst Jonathan Spyer. This means that both the authorities and the demonstrators face hard choices in the phase now opening up, he writes for the Jerusalem Post. The authorities need to find a way to delegitimize the protesters as a prelude to the use of greater force.

The Iranian protests have not become a revolution yet, adds analyst Jonathan Spyer. This means that both the authorities and the demonstrators face hard choices in the phase now opening up, he writes for the Jerusalem Post. The authorities need to find a way to delegitimize the protesters as a prelude to the use of greater force.

“The wall of fear has fallen already and what we are able to now see is that Iranians from every walk of life–including the most devout and traditional — despise this regime and will not stop until it is removed from power,” said Mariam Memarsadeghi, a fellow for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and a founder of the Cyrus Forum.

While the Biden administration’s newly released National Security Strategy is new, much of it relies on the old logic that countering the autocracy of our rivals requires tolerating it in our Middle Eastern partners, POMED Executive Director Tess McEnery writes for the Hill in Democracy Over Autocracy: The Missing Middle East.

How could the ongoing protests in Iran be felt in Arab states, from neighboring Iraq to the monarchies of the Gulf? asks Frederick Deknatel, the Executive Editor of Democracy in Exile, the DAWN journal.

Iran’s Green protest movement of 2009 was the precursor to the so-called “Arab Spring” uprisings. Now, it is happening again, notes Hayat Alvi, an associate professor at the U.S. Naval War College. The Arab Spring never ended. It became dormant, but its spirit and pro-democracy and human rights activists are still stirring, organizing and preparing for the next iteration of the Arab Awakening (which is a better title for it).

Iran’s Green protest movement of 2009 was the precursor to the so-called “Arab Spring” uprisings. Now, it is happening again, notes Hayat Alvi, an associate professor at the U.S. Naval War College. The Arab Spring never ended. It became dormant, but its spirit and pro-democracy and human rights activists are still stirring, organizing and preparing for the next iteration of the Arab Awakening (which is a better title for it).

The Iranian struggle is not just a struggle of women seeking autonomy, but also of minority ethno-religious groups seeking equality and representation in the nation, argues Marsin Alshamary, a research fellow with the Harvard Kennedy School’s Middle East Initiative. As such, these protests are compelling activists throughout the region who have an inclusive definition of democracy.

Iran’s protests create greater urgency for the Tunisian state, and others like it, to control the information environment and undermine critics challenging the status quo, adds Tunisian political analyst Seifeddine Ferjani. We should expect more efforts by repressive states to seek to disinform and challenge the narrative that questioning state authority is fruitful, or that an alternative will make things better, as the state itself is stretched.

A close analysis of hard data about current Arab views on democracy and human rights reveals some counterintuitive findings, according to a recent report from the Washington Institute for Near East Policy:

A close analysis of hard data about current Arab views on democracy and human rights reveals some counterintuitive findings, according to a recent report from the Washington Institute for Near East Policy:

• What Arab publics want most from democracy is not elections but other integral elements: less corruption, better services, more effective governance, greater individual freedoms, and economic opportunity.

• In fact, it is precisely in those Arab states where comparatively free elections have been held lately—Tunisia, Lebanon, and Iraq—that publics are increasingly dissatisfied with their own governments relative to other stable countries polled.

• And it is in those relatively democratic countries where more people support mass protests today. In the original Arab Spring countries such as Egypt and Bahrain, and in Jordan and the Gulf states, views on the benefits of protest are split.

• One important common denominator is a decline in popular support for Islamist parties and movements, as measured by numerous surveys. The Muslim Brotherhood, Hamas, Hezbollah, Tunisia’s Ennahda, and similar contenders have lost a considerable portion of their earlier appeal.

• Moreover, the proportions who want to “interpret Islam in a more moderate, tolerant, and modern direction” now make up large minorities of the Arab Gulf states polled, at around 30%–40%.

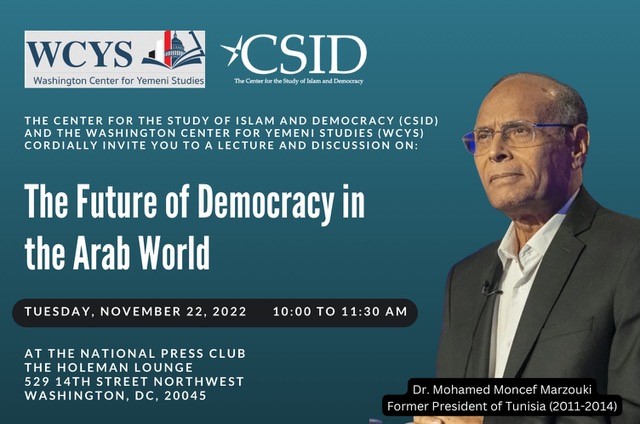

Mohamed Moncef Marzouki is the first democratically-elected President of Tunisia (2011 to 2014), January 14th Revolution in 2011, and is currently a Senior Fellow with the Democracy in Hard Places Initiative at the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, at Harvard University, in Cambridge, Mass.

Mohamed Moncef Marzouki is the first democratically-elected President of Tunisia (2011 to 2014), January 14th Revolution in 2011, and is currently a Senior Fellow with the Democracy in Hard Places Initiative at the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, at Harvard University, in Cambridge, Mass.

The Future of Democracy in the Arab World: What went wrong with the “Arab Spring”, and how to fix it? with former Tunisian President Mohamed Moncef Marzouki. Tuesday, November 22, 2022. 10:00 to 11:30 AM. At the National Press Club, The Holeman Lounge, 529 14th Street Northwest, Washington, DC, 20045. RSVP

Terrific event in Washington DC this weekend: “Iran Rising, an exhibit of Iranian protest art curated and designed by a team of all-women Iranian-American designers and artists.” Free and open to the public on Saturday Nov 19th and Sunday Nov 20th. https://t.co/rmliKyBpUP pic.twitter.com/aNqOZy84kv

— Karim Sadjadpour (@ksadjadpour) November 17, 2022