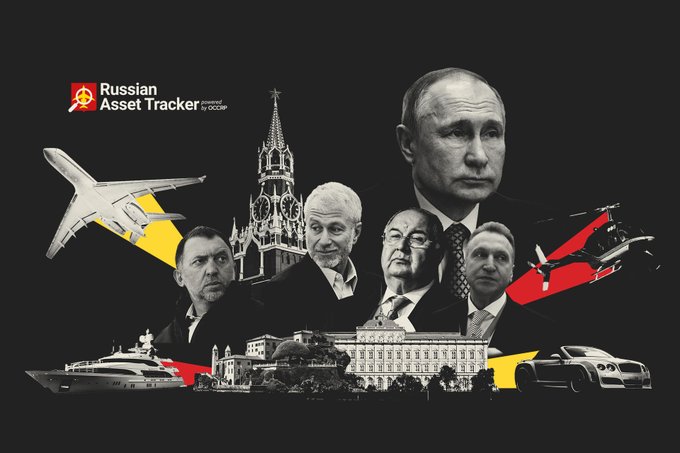

The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project has uncovered over $17.5 billion in assets tied to Russia’s ruling oligarchs.

The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project has uncovered over $17.5 billion in assets tied to Russia’s ruling oligarchs.

The group used its Russian Asset Tracker to look for land, mansions, companies, boats, planes, and anything else of value that could be tied through documentary evidence to Putin’s circle, it reports:

Some of these assets have been reported before. Some are being revealed here for the first time. Some are still to be discovered: We’ll keep searching for more properties and yachts, adding more names, and updating this database regularly. If you are aware of anything we’ve missed, please let us know by filling out this form.

Using a network of banks, law firms and advisers in multiple countries, Roman Abramovich invested billions in American hedge funds, The New York Times reports:

Using a network of banks, law firms and advisers in multiple countries, Roman Abramovich invested billions in American hedge funds, The New York Times reports:

Mr. Abramovich has an estimated fortune of $13 billion, derived in large part from his well-timed purchase of an oil company owned by the Russian government that he sold back to the state at a massive profit. This month, European and Canadian authorities imposed sanctions on him and froze his assets, which include the famed Chelsea Football Club in London. The United States has not placed sanctions on him.

Imprisoned Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny has described Abramovich as “one of the key enablers and beneficiaries of Russian kleptocracy.”

A superyacht belonging to a sanctioned Russian oligarch has been seized in Gibraltar, becoming the latest vessel to be impounded by authorities, The Guardian reports. The $75m (£57m) Axioma belonging to billionaire Dmitry Pumpyansky – owner and chairman of steel pipe manufacturer OAO TMK, which is a supplier to Russian state-owned energy company Gazprom – was seized by authorities in the British overseas territory on Monday.

Last week, the Internal Revenue Service asked Congress for more resources as it helps to oversee the Biden administration’s sanctions program along with a new Justice Department kleptocracy task force, The Times adds. And on Capitol Hill, lawmakers are pushing a bill, known as the Enablers Act, that would require investment advisers to identify and more carefully vet their customers.

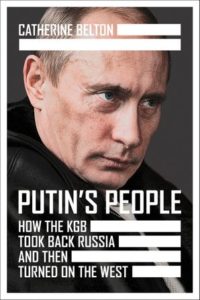

Abramovich sued Catherine Belton and HarperCollins, author and publisher of “Putin’s People,” highlighting another reason kleptocrats favor ‘Londonograd’ – libel tourism.

Abramovich sued Catherine Belton and HarperCollins, author and publisher of “Putin’s People,” highlighting another reason kleptocrats favor ‘Londonograd’ – libel tourism.

One great irony of the story that Oliver Bullough relates in his new book, “Butler to the World,” is that, after decades of obliging the global criminal élite, Britain now has a singular opportunity to turn the tables, notes Patrick Radden Keefe. Lured by “Tier 1” visas and luxury real estate and fabulous shopping and the comfortable prospect of lasting impunity, the oligarchs entrusted their fortunes to the butlers of Britain. If the British government were to have a genuine change of heart and start demanding transparency and freezing assets, a sanctuary could become a snare, he writes for The New Yorker.

In 1999, Boris Yeltsin and his oligarchic allies agreed that an obscure former KGB officer named Vladimir Putin was the man to become Yeltsin’s prime minister, and soon Russia’s next president, adds NPR’s Greg Rosalsky. He was a nobody, barely a public figure, but he had a reputation for loyalty. They trusted that, once in power, he would look after their interests. Little did they know that they were unleashing a monster they soon would be unable to control.

We are watching the rise of what the FT’s Tom Burgis has called Kleptopia (above). An undeclared, unconventional war between kleptocracy and democracy has been under way since long before Putin’s troops marched into Ukraine, he writes for The Guardian. The two sides are not arranged merely by geography. The kleptocrats have plenty of allies in the west, from the lawyers shielding their plunder to the politicians advancing their influence within democratic governments. Their victims include both Ukrainian civilians and Russian conscripts. With whom do we stand?

The National Endowment for Democracy (NED) reports that oligarch gifts are often commingled with money from other sources (some stains need pre-soaking), but they’re then leveraged to influence academic direction, secure campus speaking opportunities, and (shocker) gain admission for family members, writes @NYUStern Professor Scott Galloway.

@ThinkDemocracy author @OliverBullough‘s new book suggests how Russian oligarchs’ favorite ‘Londonograd’ could shift from sanctuary to snare, @NewYorker‘s @praddenkeefe writes in a must-read

https://t.co/bjFcvOuS5Z— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) March 22, 2022