In the immediate aftermath of the horrific mass shooting at a Florida high school on Wednesday, an army of fake accounts began pumping out disinformation on Twitter using the #ParklandShooting hashtag, Wired reports, amplifying hyper-partisan rhetoric, co-opting messaging from far-right extremists and the N.R.A., and generally sowing fresh chaos in an already chaotic breaking-news environment [HT: Vanity Fair].

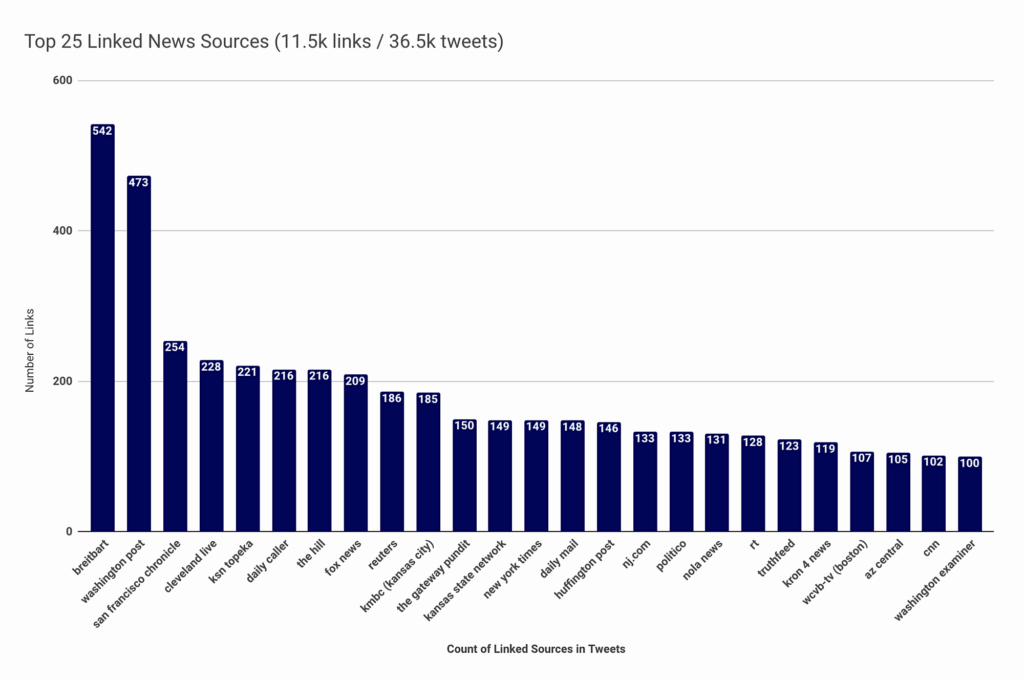

Russia’s disinformation campaign during the 2016 presidential election relied heavily on stories produced by major American news sources to shape the online political debate, according to an analysis (see below) published Thursday, The Washington Post reports:

The analysis by Columbia University social-media researcher Jonathan Albright of more than 36,000 tweets sent by Russian accounts showed that obscure or foreign news sources played a comparatively minor role, suggesting that the discussion of “fake news” during the campaign has been somewhat miscast.

The analysis by Columbia University social-media researcher Jonathan Albright of more than 36,000 tweets sent by Russian accounts showed that obscure or foreign news sources played a comparatively minor role, suggesting that the discussion of “fake news” during the campaign has been somewhat miscast.

Albright’s research, which he said is the most extensive to date on the news links that Russians used to manipulate the American political conversation on Twitter, bolsters observations by other analysts. Clinton Watts, a former FBI agent who is now a disinformation expert at the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Philadelphia, said that by linking to popular news sources, the Russians enhanced the credibility of their Twitter accounts, making it easier to manipulate audiences.

“They’re really trying to drive the news conversation,” Albright said. “They’re trying to set the agenda.”

Top election officials from around the country will be meeting in Washington, D.C., this weekend amid a flurry of news reports and political debates over the last two weeks about election security, The Washington Free Beacon adds.

“In a good misinformation campaign, Russian bots on Twitter or fake accounts on Facebook will actually make use of the most credible news sources in America. Even news stories that debunk some political rumor can be used to keep the rumor alive,” said Phil Howard of the University of Oxford’s Computational Propaganda Project.

“In a good misinformation campaign, Russian bots on Twitter or fake accounts on Facebook will actually make use of the most credible news sources in America. Even news stories that debunk some political rumor can be used to keep the rumor alive,” said Phil Howard of the University of Oxford’s Computational Propaganda Project.

Moscow’s actions are part of a broader global effort and China is also taking steps to expand its overseas influence, notes Thomas E. Kellogg, the executive director of the Georgetown Center for Asian Law. This week’s Senate intelligence hearing made clear that more needs to be done, both to understand and to counter Chinese and Russian actions, he writes for The Washington Post:

In an important new report released last month, the Washington-based National Endowment for Democracy (NED) called attention to China and Russia’s efforts to increase their global reach. That report, “Sharp Power: Rising Authoritarian Influence,” is one of the most authoritative studies to date on the ways in which China and Russia are developing a diverse tool kit to increase their overseas political influence.

In an important new report released last month, the Washington-based National Endowment for Democracy (NED) called attention to China and Russia’s efforts to increase their global reach. That report, “Sharp Power: Rising Authoritarian Influence,” is one of the most authoritative studies to date on the ways in which China and Russia are developing a diverse tool kit to increase their overseas political influence.

Michael O’Hanlon, a senior foreign policy fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, said that this week’s Munich Security Conference follows the Trump administration’s recent unveiling of its national defense and security strategies portraying China and Russia as “revisionist” powers and outlining an increased focus on “great power competition,” RFE/RL reports.

“Hearing more about what it means to make Russia and China our main national security emphases will, I think, be a question a lot of people will want to explore with Secretary Mattis and General McMaster, and anybody else from the U.S. delegation” in Munich, O’Hanlon said.

Social media could be just the start of a slippery slope leading to an Orwellian world controlled by Big Data Brother, accelerated by convergence with the sensors in our devices and rapid advances in artificial intelligence, notes former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan. Some authoritarian regimes are already marshaling these developments to exercise control on an unprecedented scale, he writes for Project Syndicate.

Under the auspices of the Kofi Annan Foundation, he plans to convene a new commission “to find workable solutions that serve our democracies and safeguard the integrity of our elections, while harnessing the many opportunities new technologies have to offer,” he adds. “We will produce recommendations that will, we hope, reconcile the disruptive tensions created between technological advances and one of humanity’s greatest achievements: democracy.”

As Russia’s belligerent behavior in the international arena continues to raise concerns, analyst Thomas Hodson investigates the Kremlin’s attempts to manipulate the language of international law to justify its actions. [HT: IMR]

Russian efforts to influence the 2016 US presidential election represented “the most recent expression of Moscow’s longstanding desire to undermine the US-led liberal democratic order, but these activities demonstrated a significant escalation in directness, level of activity, and scope of effort compared to previous operations,” according to a declassified memo on Assessing Russian Activities and Intentions in Recent US Elections from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

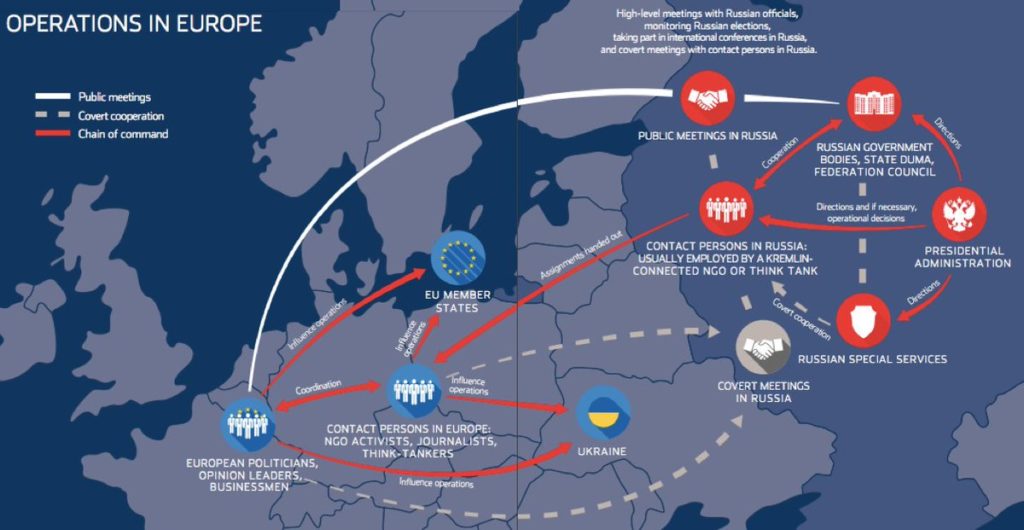

For Russian special services, influence operations are an inexpensive, effective and well-established instrument in their arsenal, according to the Estonian Foreign Intelligence Service. The capability in the field of information warfare is growing (see graphic above) and Russia is already well-prepared for more extensive disinformation campaigns, it adds in a must-read report:

Russia will continue its attempts to influence democratic decision-making processes in the West, especially in EU countries that have elections in 2018. The Kremlin believes that creating confusion in Western countries gives Russia greater freedom of action and increases its influence. Increasingly Russia believes that the state is forced to wage a hidden political struggle against the West and this self-delusion is spurring it to expand its influence operations and information warfare capability. That means disseminating even more disinformation and more attempts to recruit Western politicians, businessmen and opinion leaders abroad.

But we should be wary of suggestions that fake news or disinformation is likely to change people’s votes in an election since a growing number of studies conclude that most forms of political persuasion have little effect, according to Brendan Nyhan, a professor of government at Dartmouth College.

But we should be wary of suggestions that fake news or disinformation is likely to change people’s votes in an election since a growing number of studies conclude that most forms of political persuasion have little effect, according to Brendan Nyhan, a professor of government at Dartmouth College.

Field experiments testing the effects of online ads on political candidates and issues have also found null effects, he writes for The New York Times:

We shouldn’t be surprised — it’s hard to change people’s minds! Their votes are shaped by fundamental factors like which party they typically support and how they view the state of the economy. “Fake news” and bots are likely to have vastly smaller effects, especially given how polarized our politics have become…..

The total number of shares or likes that fake news and bots attract can sound enormous until you consider how much information circulates online. Twitter, for instance, reported that Russian bots tweeted 2.1 million times before the election — certainly a worrisome number. But these represented only 1 percent of all election-related tweets and 0.5 percent of views of election-related tweets.

Fake news has become big news. Post-truth is the new paradigm. Respect for facticity is becoming, by all accounts, a commercial anachronism. And behind it all, the spectre of an illiberal international waging ‘info-war’ against western democracies, Eurozine adds:

Fake news has become big news. Post-truth is the new paradigm. Respect for facticity is becoming, by all accounts, a commercial anachronism. And behind it all, the spectre of an illiberal international waging ‘info-war’ against western democracies, Eurozine adds:

Fake news and disinformation are real and they are dangerous. Their emergence lays bare the vulnerabilities of liberal democracy in globalized, digitally networked societies. And yet we need to be careful about the conclusions we draw. Blaming a combination of digital technologies and the forces of illiberalism only goes so far. We also need to look at the demand side: how are the political and cultural forces that catalyse the spread of disinformation inherent to our own democratic systems?

The upcoming elections in Latin America will increase the use of fake news, Open Democracy suggests:

The upcoming elections in Latin America will increase the use of fake news, Open Democracy suggests:

It has been proven that politicians and parties wish to manipulate public opinion regardless of the consequences, and without definite solutions the biggest threats to fake news are the very citizens themselves.

There are important initiatives originating from groups of activists and journalists that carry out fact checking, such as Chequeados in Argentina and ColombiaCheck in Colombia. In spite of their efforts however, it is important that citizens generate a more critical eye with regards to the information they consume and when faced with suspicious news sources, they must learn not to share them.

Coda Story’s mini-documentary series Jailed for a Like has just been shortlisted for the prestigious European Press Prize, notes Simon Ostrovsky, Investigations Editor:

Last year every eight days a Russian was given a prison sentence for his or her activity on social media. Our series follows the stories of those prosecuted, from a poet fined for his verses in support of Ukraine to a blogger sentenced to two years in prison for criticizing Russia’s bombing campaign in Syria. Watch the full series here and keep an eye out for the next episode coming soon.

Berkman Klein Center