A global ideological competition is brewing between liberal democracy and authoritarianism, with China as the wealthiest and most powerful potential leader on the authoritarian side, according to a new analysis.

But competition over standards “does not need to be ideological,” notes “Course Correction: Toward an Effective and Sustainable China Policy”, a report from the Asia Society’s Center on U.S.-China Relations and UC San Diego’s 21st Century China Center.

“It is simply an issue of which approach provides the most significance and most benefits to the largest number of people,” it adds. “To be sure, liberal democratic values give the United States an edge, but the United States should seek to maximize that edge by being more actively engaged.”

“[W]hile respecting the independence of civil society organizations, the relevant agencies of the U.S. government should consider providing more financial and technical assistance to U.S. human rights, religious, educational, media, and other organizations that are working to promote human rights in China,” the report recommends:

“[W]hile respecting the independence of civil society organizations, the relevant agencies of the U.S. government should consider providing more financial and technical assistance to U.S. human rights, religious, educational, media, and other organizations that are working to promote human rights in China,” the report recommends:

The U.S. government should sustain and increase funding for Chinese organizations and individuals, both inside China and in exile, who are working to promote internationally recognized human rights in the country. Such allocations should include funding for capacity-building initiatives that could be offered for Chinese lawyers, media workers, and other human rights activists in settings outside China. Such funding could be directed through the State Department Bureau of Democracy, Rights, and Labor; the Agency for International Development; and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and its four core institutes. (Because of its demand-driven, small-grants model, the NED is particularly successful in supporting rights promotion with high effectiveness and low cost.)

U.S. human rights diplomacy should tap into Asian solidarity whenever possible by coordinating more closely with democratic Asian governments and NGOs, the authors add.

The U.S. “should neither stop advocating for its own liberal democratic values, nor surrender hope that many Chinese share these values. A deeply rooted liberal tradition exists in China, even if it has been temporarily forced into quiescence by the present resurgence of authoritarian controls,” the report notes:

The U.S. “should neither stop advocating for its own liberal democratic values, nor surrender hope that many Chinese share these values. A deeply rooted liberal tradition exists in China, even if it has been temporarily forced into quiescence by the present resurgence of authoritarian controls,” the report notes:

But it is far from dead, and its suffocation by the party leaves many Chinese intellectuals quietly chafing. We should not forget that the party’s dictatorial rule has always waxed and waned and that the tolerance of the urban middle class for repression could well weaken as economic growth slows. Moreover, we would forget at our peril the ways in which China has unpredictably changed in the past and will certainly do so again in the future.

The roots of current U.S.-China tensions lie in Xi Jinping’s authoritarian turn, the report suggests:

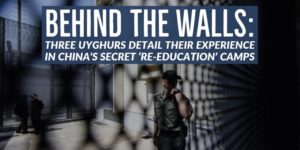

By making a U-turn back to personalistic dictatorship, Leninist party rule, and enforced ideological conformity, Xi has created new obstacles to engagement with the United States and other liberal democracies around the world, while also erecting barriers to Chinese interactions with foreign civil society institutions such as universities, think tanks, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). One of the most egregious examples of the return to Mao-era repressive practices is the round-up of hundreds of thousands of Muslims in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and their confinement in camps where they are forced to undergo intensive “re-education” aimed at weakening their religious convictions and strengthening their loyalty to the Chinese party-state….

By making a U-turn back to personalistic dictatorship, Leninist party rule, and enforced ideological conformity, Xi has created new obstacles to engagement with the United States and other liberal democracies around the world, while also erecting barriers to Chinese interactions with foreign civil society institutions such as universities, think tanks, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). One of the most egregious examples of the return to Mao-era repressive practices is the round-up of hundreds of thousands of Muslims in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and their confinement in camps where they are forced to undergo intensive “re-education” aimed at weakening their religious convictions and strengthening their loyalty to the Chinese party-state….

The report notes that “Beijing also sometimes cheats, other times ignores, and occasionally outright opposes international law rulings and standards to leverage its participation in global governance forums to push international norms in directions that benefit authoritarian regimes at the expense of liberal democratic systems and values” – a clear reference to China’s exercise of sharp power.

The report notes that “Beijing also sometimes cheats, other times ignores, and occasionally outright opposes international law rulings and standards to leverage its participation in global governance forums to push international norms in directions that benefit authoritarian regimes at the expense of liberal democratic systems and values” – a clear reference to China’s exercise of sharp power.

Yet Russia and China “present very different challenges,” the report states.

“Vladimir Putin aims to destabilize and subvert Western democracies, while China’s leaders instead have tried to influence Western narratives about China in an effort to win acceptance and favor for its economic development model and its one-party system of government.”