The Covid pandemic is presenting political parties with severe challenges – and unique opportunities, analysts suggest.

Peruvians woke up Monday morning without a president, after Congress failed to agree on a successor for a leader who himself only lasted five days in power, notes Patricia Navia, a professor of liberal studies at NYU and professor of political science at Diego Portales University in Chile. Legislators will probably work things out and name a replacement in coming days. But Peru will continue to face the same core problem, one that is undermining democracies across Latin America: The absence of stable, institutionalized political parties, she writes for Americas Quarterly:

The core problem is not new. As long ago as 2003, political scientists Steven Levitsky and Maxwell A. Cameron (Democracy Without Parties? Political Parties and Regime Change in Fujimori’s Peru) pointed to the absence of a political party system in Peru. When former president Alberto Fujimori resigned on November 20, 2000 (via fax from Japan, when his effort to stay for a third consecutive 5-year term unraveled), Peru embarked on a transition to democracy without well-functioning political parties. Experts on democratic theory have historically asserted that democracy cannot exist without parties. In 1991 (Democracy and the Market), Adam Przeworski defined democracy as “systems where parties lose elections.”

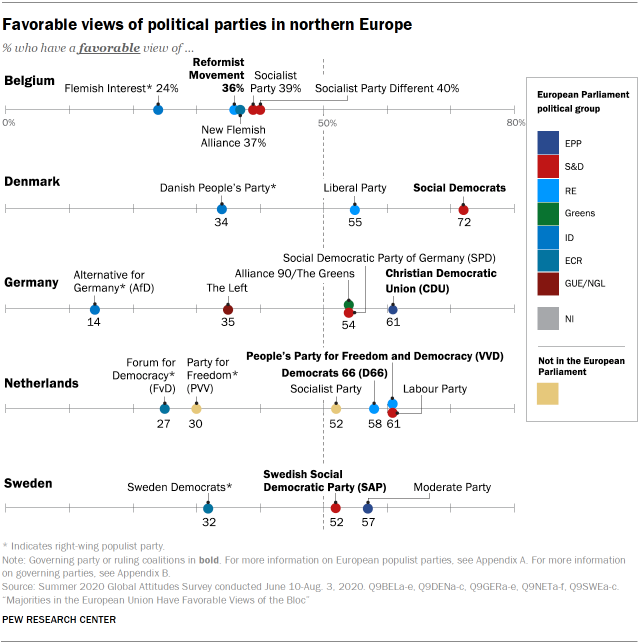

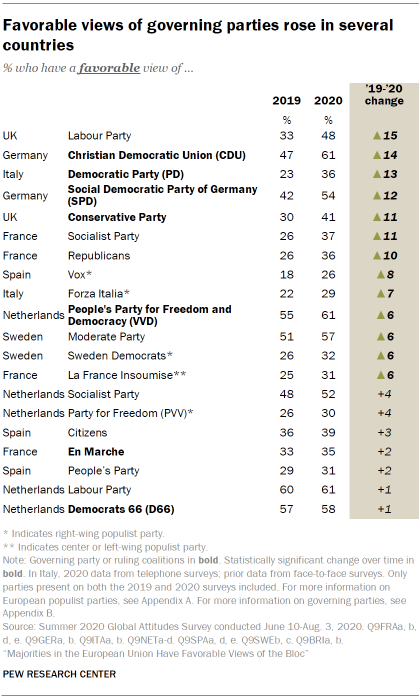

In 2019, when Pew Research Center asked about party favorability in Europe, few parties received positive marks from at least half the population. But, among the 40 parties tested in summer 2020, 11 were seen favorably by more than 50% in each country, note Pew analysts , AND

Across all northern European countries surveyed except Belgium, at least one party per country met this threshold. The same is not the case when it comes to southern European countries, however. In France, Spain and Italy, no party earned approval from more than half, and in the case of most parties tested in these three countries, few cracked 40%. In the United Kingdom, 48% reported positive opinions of the opposition Labour Party, while all other parties tested fall short of this mark, they observe:

Across the seven European countries surveyed over the summer – when the coronavirus appeared to be largely under control across the region – there was a strong relationship between favorable views of the governing party that held the most seats in the government and the sense that the government had done a good job handling COVID-19. For example, Denmark stood apart as both the European country where the highest percentage said their government had done a good job dealing with the coronavirus pandemic (95%) and as the home to the party (the Social Democrats) that garnered the highest approval ratings (72%). In contrast, in the UK – where only 46% said their country had done a good job with the pandemic, the lowest in Europe – the Conservative Party in power was liked by only 41% of the public.

But political parties are failing to adjust to the pandemic in ways that allow women to maintain levels of political participation, according to a new Carnegie analysis.

Given the impact of the crisis on many women’s financial power, new strategies need to be instituted to recruit women to run for office and provide financial and logistical support for those who do, argue Saskia Brechenmacher, a fellow in Carnegie’s Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program, and Caroline Hubbard (below), the senior gender adviser and deputy director for the Gender, Women, and Democracy Program at the National Democratic Institute, a core partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED):

Given the impact of the crisis on many women’s financial power, new strategies need to be instituted to recruit women to run for office and provide financial and logistical support for those who do, argue Saskia Brechenmacher, a fellow in Carnegie’s Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program, and Caroline Hubbard (below), the senior gender adviser and deputy director for the Gender, Women, and Democracy Program at the National Democratic Institute, a core partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED):

Political parties or election monitoring bodies can make dedicated funding available to female candidates—whether in the form of pooled campaign funds or earmarked party financing. Donors and local civil society actors can push for campaign finance rules and monitor their enforcement; those that work directly with political parties should also increase pressure on party leaders to abide by candidate selection rules, ensure gender balance on pandemic-related committees, and recruit qualified female candidates.

The median governing party in democracies has become more illiberal in recent decades, according to recent research from Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V-Party), a new dataset, produced by the V-Dem Institute. This means that more parties show lower commitment to political pluralism, demonization of political opponents, disrespect for fundamental minority rights and encouragement of political violence.