Oxford Internet Institute’s ComProp Navigator

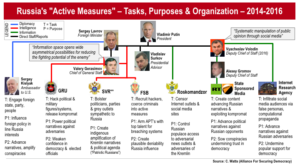

China and Russia are increasingly collaborating and engage in mutual learning when it comes to disinformation strategies, says analyst Jane Lihe sentiment among China’s internet users is that Russia’s media strategy remains far more effective, she

Beijing has tried to project the Hong Kong protests overseas as an extremist-fueled separatist movement using state-run media and through fake Twitter accounts—but these efforts haven’t been particularly sophisticated. In comparison, Russia’s strategy of using social media handles cultivated over years to wade into divisive topic in other countries has blended into western discussions more successfully and helped Kremlin to sow confusion and distrust. Now the two countries are trying to work more closely together on their global messaging.

“China has been studying the propaganda strategies of Russia, including how the latter manipulates media, mobilizes its youth and trains its hackers. The two countries’ state-owned outlets, including Global Times and Russian state-owned news agency Sputnik have had regular people exchanges,” said Wu Qiang, a former politics lecturer at China’s Tsinghua University in Beijing, who has been studying the two countries’ collaboration in their media campaigns.

From the period of time before World War II up to the end of the Cold War, the primary targets of Soviet disinformation campaigns, those who were called at the time “useful idiots,” were either convinced Communists or left-liberals who agreed in part with the Soviet Union’s ideological attacks on the policies of Western governments, notes Jeffrey Herf, Distinguished University Professor in the Department of History at the University of Maryland in College Park. An excursion into the not-so-distant past helps to remind us of two points, he writes for The American Interest:

From the period of time before World War II up to the end of the Cold War, the primary targets of Soviet disinformation campaigns, those who were called at the time “useful idiots,” were either convinced Communists or left-liberals who agreed in part with the Soviet Union’s ideological attacks on the policies of Western governments, notes Jeffrey Herf, Distinguished University Professor in the Department of History at the University of Maryland in College Park. An excursion into the not-so-distant past helps to remind us of two points, he writes for The American Interest:

- First, as the story of….Soviet fictional narratives indicates, when it served its interests the Soviet Union was willing and able to spread disinformation that benefited the Western left and undermined the Western right. Putin’s Russia, which seethes with resentment about American power, could certainly find reasons in the near future to support leftists eager to dismantle Western defenses and pursue a leftist version of “America First” that would, for example, oppose “endless regime-change wars.”

-

Clint Watts/Alliance for Securing Democracy

Second, this historical excursion underscores the point made by Senator King—namely, the endurance and continuing relevance of the Soviet legacy in Putin’s Russia. Historians know that societies and polities change very slowly, even when dramatic events such as regime-change occur. The weight of the past is heavy.

“Russia is no longer communist,” Herf adds, “but the skills needed to spread deception and deflect blame onto others, honed for decades by the Soviet intelligence services, are very much at work in Russia’s current attacks on our democracy.”

The UK’s General Election highlights the widening use of techniques to manipulate social media by candidates, parties, activist groups and individuals around the world, says a leading analyst.

The UK’s General Election highlights the widening use of techniques to manipulate social media by candidates, parties, activist groups and individuals around the world, says a leading analyst.

The use of disinformation techniques by political leaders, particularly the Conservatives, led by Prime Minister Boris Johnson, reflects an evolution in how the internet is being used to grab attention, distract the news media, stoke outrage and rally support, The New York Times reports:

It is not just professionals who are creating false or misleading campaign material online. Just about anyone can put it together, and that is exactly what seems to be happening….Polls suggest that voters are shrugging off accusations of online trickery, as Facebook has said it will not screen political ads for accuracy. Experts said this means the tactics were likely to further enter the mainstream in Britain and elsewhere.

“It’s the democratization of misinformation,” said Jacob Davey, a senior researcher at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a London-based group that tracks global disinformation campaigns. “We’re seeing anyone and everyone picking up these tactics.”

“It’s the democratization of misinformation,” said Jacob Davey, a senior researcher at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a London-based group that tracks global disinformation campaigns. “We’re seeing anyone and everyone picking up these tactics.”

“This is the election where disinformation was normalized,” he said. “A few years ago people were looking for a massive coordinated campaign from a hostile state actor. Now, many more actors are getting involved.”

Cybersecurity for civil society

Researchers at the Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford, have launched ‘The ComProp Navigator‘ (above), a new online resource guide which aims to help civil society groups better understand and respond to the problem of disinformation.

Oxford Internet Institute: ComProp Navigator

Developed by the OII’s Project on Computational Propaganda, led by Professor Philip Howard, the ComProp Navigator directs users to a range of online resources including bite-size guides, in-depth analyses, practical guides, fact-checking sites, helplines, online courses, and others. The launch of the site follows a series of civil society workshops held over the last two years with practitioners and journalists about navigating the disinformation landscape. The online curation tool recommends resources to help identify or manage:

- The mechanics, elements and scope of disinformation

- Strategies for dealing with disinformation

- Avoiding amplification of junk news, maintaining public trust

- Cybersecurity for civil society

- Online harassment and doxxing risks

Claire Wardle of First Draft

The disinformation campaigns seen in the British election appear designed to be easily discovered, provoke outrage and distract the news media, said Jenni Sargent, managing director of First Draft, a nonprofit group that investigates online misinformation, The Times adds:

She said that whenever journalists questioned Conservative Party representatives about the questionable tactics, they used the opportunity to criticise opponents in the Labour Party.

Lisa-Maria Neudert, a researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute who tracks social media use in the British election, said it was worrying that mainstream campaigns were so involved. “It’s about winning at any price,” she said. “The difficulty is so much of this is legal. Much of it is just falling through the gaps of the law.”