Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo and former military general Prabowo Subianto will face off in a presidential election on Wednesday (Nikkei/CFR), with official results expected take up to a month to report. Subianto led a unit accused of abducting democracy activists in the 1990s.

Mr. Joko’s likely victory over Mr. Prabowo on Wednesday will come as a relief to many Indonesian liberals and minority groups, says Ross Tapsell, a researcher and Indonesia specialist at the Australian National University’s College of Asia and the Pacific.

NDI

Yet they should be worried about the latest practices of a president once heralded as a democratic reformer. That Mr. Joko’s government has chosen to respond to disinformation with disinformation signals a dangerous backsliding for democracy in Indonesia, he writes for The Times.

Civil society groups and NGOs backed Joko in the hope that he would defend minority rights. But this election is being fought against a very different backdrop, say observers, arguing that the blasphemy case has acted as a catalyst for a rise in intolerance in the country, The FT reports.

“The religious polarisation of elections in Indonesia, long believed to be on the decline, reached new heights [with the anti-Ahok protests],” wrote Marcus Mietzner, assistant professor at Australian National University, in a recent paper. Speaking to the Financial Times, Mr Mietzner adds: “Jokowi deserves a lot of blame for not countering the intensifying Islamist discourse with a compelling pluralist narrative. Instead, he tried to adopt many of the Islamists’ themes — and the minorities were the main victims of that move.”

Election day results that are tighter than Widodo’s narrow 2014 victory over Subianto are quite possible, AP adds, because “the polls haven’t been able to capture the grassroots dynamics,” said Alexander Arifanto, a researcher at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore. “Subianto’s campaign has had more zeal and spirit than Jokowi’s side,” he said.

Election day results that are tighter than Widodo’s narrow 2014 victory over Subianto are quite possible, AP adds, because “the polls haven’t been able to capture the grassroots dynamics,” said Alexander Arifanto, a researcher at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore. “Subianto’s campaign has had more zeal and spirit than Jokowi’s side,” he said.

In recent years, the country’s Muslim majority has embraced more overt signs of religiosity and shifted toward Arab-style devotion….. Most of all, a puritanical Salafist interpretation of Islam, which draws inspiration from the age of the Prophet Muhammad, is attracting followers in Indonesia, The Times adds:

“Political Islam has strengthened tremendously over the last two decades in Indonesia,” said Andreas Harsono, an Indonesia researcher for Human Rights Watch and author of the new book “Race, Islam and Power.” “We should be very concerned, because both sides in the campaign have now made human rights and democracy decline.”

“Political Islam has strengthened tremendously over the last two decades in Indonesia,” said Andreas Harsono, an Indonesia researcher for Human Rights Watch and author of the new book “Race, Islam and Power.” “We should be very concerned, because both sides in the campaign have now made human rights and democracy decline.”

Pundits are questioning the quality of Indonesian democracy, amidst growing repression, rising conservatism, coupled with growing Islamism and anti-feminist trends, analyst Yohanes Sulaiman writes for The Conversation. Not surprisingly, many believe a lot is at stake in these elections. It is, in essence, a battle between flawed technocratic reformers who nevertheless represent a moderate, inclusive Indonesia, versus nationalist populists who court hard-line Islamist groups with illiberal agenda.

Widodo is trying to convince voters in this fourth most populous nation of 260 million people to award him a second, five-year term, despite a shortfall in economic growth, persistent inequality, the rising power of Islamist hard-liners and his administration’s illiberal drift, the Wall Street Journal adds (HT:FDD).

Unfortunately, we do not expect to see Indonesia’s maturing democracy produce a “break out” figure who can push ahead with the type of reforms needed to turn the country into a manufacturing powerhouse akin to some of its neighbors, Control Risks analysts Achmad Sukarsono and Dane Chamorro write for the FT. The presidency matters less than parliament, corruption, and regional politics in shaping the environment.

LibForAll

Around 10,000 Indonesians have volunteered [HT:Foreign Policy] to act as independent observers at polling stations. This crowdsourced approach to election monitoring is being convened by the group Kawal Pemilu (Guard the Election). The organization plans to release its independently-tabulated vote count on its website in an effort to hedge against any attempts at rigging.

Their work was a hit with Indonesians who were seeking clarity on the results, TIME adds. The organization provided quick updates, pacifying Indonesians who had to wait two weeks for the country’s electoral commission to announce the official winner. The extensive data published by Kawal Pemilu was also the first time that social media and technology played an important role in monitoring the election process.

“Both sides run a massive social media campaign,” said Abdul Malik Gismar, a lecturer at Paramadina University in Jakarta. “Both sides are also using hoaxes and half-truths. It solidifies the base, at least,” he told The Times:

On Friday, Facebook removed 234 pages, accounts and groups on Facebook and Instagram that were engaged in a coordinated effort to influence the election by spreading false information. The influence effort was aimed at helping Mr. Prabowo, said the Digital Forensic Research Lab, a group that seeks to expose disinformation.

Jokowi, the front-runner, has been a poor guardian of democracy, with a single-minded focus on economic development that has come at the cost of much-needed political and legal reform, says Ben Bland, the director of the Southeast Asia Project at the Lowy Institute in Sydney. To maintain power, he has sought compromises with corrupt politicians, intolerant religious leaders, and former generals. As a result, human rights, the rule of law, and the protection of minorities have all weakened on his watch, he writes for The Atlantic.

Perhaps the most influential Saudi investment in Indonesia is the Institute for the Study of Islam and Arabic, known by the Indonesian acronym, Lipia, where classes are segregated by gender and teach the fundamentalist Wahhabi theology that dominates in Saudi Arabia, The Times adds.

Perhaps the most influential Saudi investment in Indonesia is the Institute for the Study of Islam and Arabic, known by the Indonesian acronym, Lipia, where classes are segregated by gender and teach the fundamentalist Wahhabi theology that dominates in Saudi Arabia, The Times adds.

“Even though Indonesian Islam is a syncretic, cultural Islam, we are taught that anything from Saudi, the country of Mecca and Medina, must be authentic and good,” said Ulil Abshar Abdalla, the coordinator of the Liberal Islam Network, who studied at Lipia.

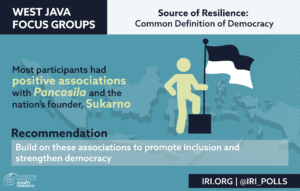

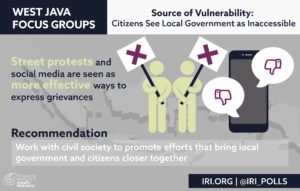

Focus group data by the International Republican Institute’s* Center for Insights in Survey Research reveals some of the key vulnerabilities to violent extremism, as well as sources of resilience to radical ideology.

“Wahhabism is against our culture, and our religion is totally different from the Middle East,” said Zuhairi Misrawi of Nahdlatul Ulama, the world’s largest Islamic social organization, who is helping set up an online presence to compete against the puritanical websites popular with young Indonesians.

“Our war is to get moderate Islam to fight for millennial Muslims who are hungry for Islam,” he said. “But people don’t see us as passionate, as charismatic. It’s hard to change this.”

N.U. has established a nonprofit organization, Bayt ar-Rahmah, in Winston-Salem, N.C., which will be the hub for international activities including conferences and seminars to promote Indonesia’s tradition of nonviolent, pluralistic Islam, The Times adds.

N.U. has established a nonprofit organization, Bayt ar-Rahmah, in Winston-Salem, N.C., which will be the hub for international activities including conferences and seminars to promote Indonesia’s tradition of nonviolent, pluralistic Islam, The Times adds.

A film, “Rahmat Islam Nusantara” (The Divine Grace of East Indies Islam – above), explores Islam’s arrival and evolution in Indonesia, and includes interviews with Indonesian Islamic scholars.

As it has elsewhere in the Muslim world, conservative dress has become more common in Indonesia, adds The Times. Polygamy and child marriage are also on the rise here, as democracy has allowed personal freedoms repressed during the Suharto era to prosper.

“Radical groups understand that they can use democracy to their advantage,” said Musdah Mulia, a professor of Islamic political thought at Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University. “They say that democracy is bad because it allows infidels to have a vote, but then they manipulate it for themselves.”

“Radical groups understand that they can use democracy to their advantage,” said Musdah Mulia, a professor of Islamic political thought at Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University. “They say that democracy is bad because it allows infidels to have a vote, but then they manipulate it for themselves.”

*All four National Endowment for Democracy institutes and a number of discretionary grantees were part of the Endowment’s long-term commitment to supporting civil society in Indonesia. NED’s unique structure, which includes two party institutes (IRI and NDI), a business institute (CIPE), and a labor institute (ACILS), allows it to offer expertise in each of these areas.

“NED funding was absolutely critical, enabling us to have an in-country presence in Indonesia,” said David Timberman in October 1998, then an NDI representative in Indonesia.