The international reputation of the United States, the world’s worst-hit country, has suffered over its handling of the covid-19 pandemic — but China, its main geostrategic rival, has struggled to capitalize on the moment, The Post reports:

The international reputation of the United States, the world’s worst-hit country, has suffered over its handling of the covid-19 pandemic — but China, its main geostrategic rival, has struggled to capitalize on the moment, The Post reports:

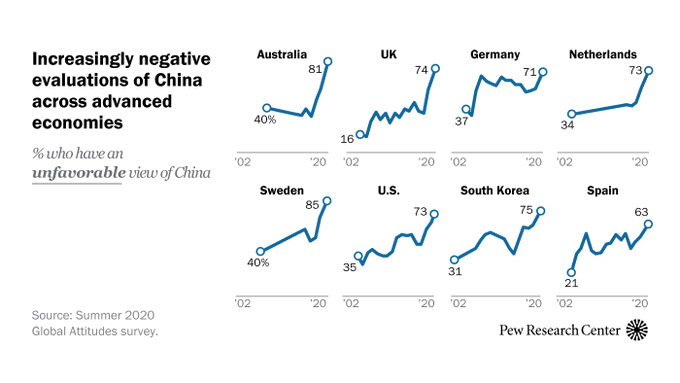

According to a survey by the Pew Research Center, conducted between June and early August, a median of 61 percent of respondents from 14 advanced economies said China “has done a bad job dealing with the virus.” The United States’ handling of the pandemic has met even deeper international skepticism, with a median of 84 percent describing its response as bad.

As democracies reenter a paradigm of great power competition with autocrats, they do so within a new context in which their system of government no longer grants absolute advantage but instead is a potential vulnerability, adds strategist James P. Micciche.

National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

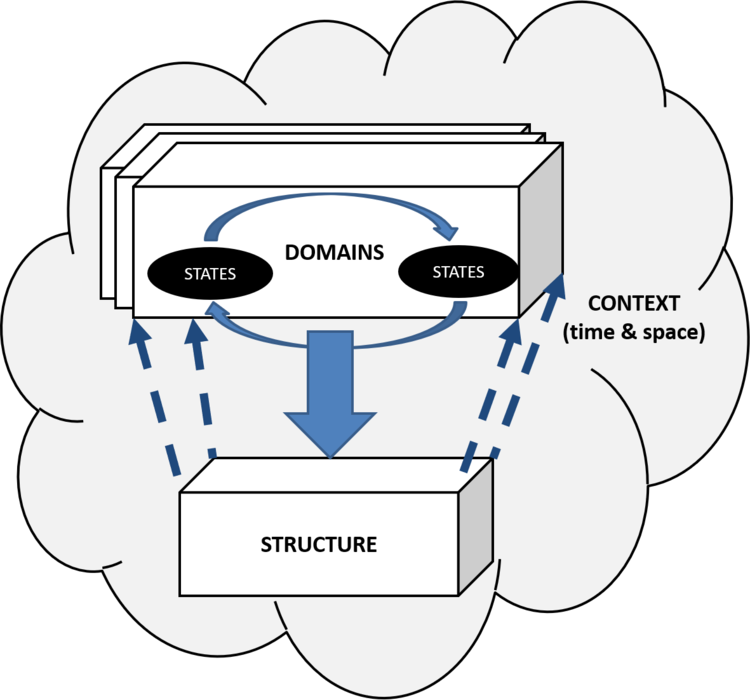

The ability for autocratic states to use sharp power, according to the National Endowment for Democracy’s Christopher Walker and Jessica Ludwig, is based upon “glaring asymmetry” within the modern international system that enables autocratic states to level the proverbial playing field in multiple power domains where democracies have traditionally enjoyed superiority and comparative advantage, he writes for RealClearDefense:

Sharp power is now an integral part of international relations and a manifestation of power that greatly reduces the ability of democratic states in competing with autocratic ones, a substantial shift in relative positions from historic perspectives. Democratic states cannot ignore the effectiveness of sharp power and must develop internal and external information dominance capabilities, doing so within the framework of liberal democracy while extending protection to vulnerable developing democracies.

This article appeared originally at Strategy Bridge.

A Visual representation of power within the international system as defined by the author. Power is not only the medium through which states interact within given domains such as economics, information, or military force but a byproduct of that interaction that creates structures that then in turn affects domains. This continuous bidirectional process is contextually based on both states and the domain in which they operate. (Credit: James Micciche)