Democracies and the rules-based international order are facing their “greatest challenge” since the Cold War, said President Tsai Ing-wen (above), calling for greater cooperation by democracies to counter authoritarian regimes.

“If we are to meet this challenge, we must work together, as democracies, to counter the tactics that authoritarian regimes use to undermine our institutions,” she told a Taipei forum marking the 20th anniversary of the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy (TFD). “By working together to first understand sharp power, we can then elaborate the best strategies to counter authoritarian influence,” Tsai added.

NED President and CEO Damon Wilson presented the Democracy Service Medal to Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-Wen.

China‘s pressure on Taiwan is “part of the broader global assault on democracy,” said Damon Wilson, President and CEO of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). “As Taiwan deepens its democracy at home, it bolsters its own security,” he told the TFD forum as he presented the NED’s Democracy Service Medal to President Tsai.

“President Tsai has been steadfast in her commitment to democracy and fostering democratic unity among like-minded nations,” Wilson added. “By honoring President Tsai’s leadership, we spotlight Taiwan’s democratic success and our commitment to the people of Taiwan that they can determine their own destiny. Here in Taipei, at the forefront of freedom, we stand in solidarity with you.” Read the full remarks here.

The future of freedom in the world depends on the preservation of freedom and security in Taiwan, said founding NED President Carl Gershman. The 20th anniversary of the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy is an occasion for celebration as it is the first and still the only democracy foundation in Asia that is committed to advancing human freedom and the rule of law around the world. In the words of its Chairman Si-kun You, the TFD is “a bastion for global democratic forces,” and that is indeed something to celebrate, he added in the following contribution:

The anniversary is also an occasion for reflection on the TFD’s role and importance at a time when Taiwan faces an existential threat from the PRC. As a symbol of Taiwan’s commitment to democracy, the TFD challenges the PRC in two fundamental ways. Like Taiwan itself, the TFD represents the idea of an indigenous democratic alternative to China’s despotic political system that is Asian and not Western. It also affirms through its mission the idea of democratic universalism, thereby challenging the PRC’s diametrically opposite mission of being what Liu Xiaobo once aptly called “a blood-transfusion machine” for the world’s other dictatorships. By embodying the two ideas of democracy and universalism, the TFD has a political weight in the conflict with China that far exceeds the scope of its programs and its all-too-modest budget.

The anniversary is also an occasion for reflection on the TFD’s role and importance at a time when Taiwan faces an existential threat from the PRC. As a symbol of Taiwan’s commitment to democracy, the TFD challenges the PRC in two fundamental ways. Like Taiwan itself, the TFD represents the idea of an indigenous democratic alternative to China’s despotic political system that is Asian and not Western. It also affirms through its mission the idea of democratic universalism, thereby challenging the PRC’s diametrically opposite mission of being what Liu Xiaobo once aptly called “a blood-transfusion machine” for the world’s other dictatorships. By embodying the two ideas of democracy and universalism, the TFD has a political weight in the conflict with China that far exceeds the scope of its programs and its all-too-modest budget.

China and the world have changed drastically since 1995 when NED initiated its cooperation with Taiwan by co-sponsoring with the Institute for National Policy Research a global conference on democracy that brought to Taiwan more than fifty of the world’s leading political scientists and democratic intellectuals. It was a rare moment of democratic optimism, dubbed by one skeptic a “vacation from history.” During the two preceding decades the number of democracies in the world had more than doubled, a process that Samuel Huntington, who keynoted the conference, had famously called “the third wave of democratization,” which was the title we gave to the conference. Taiwan was itself a proud third-wave democracy, which is why it was such an appropriate venue for that historic gathering.

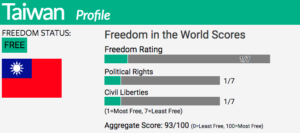

The cooperation between Taiwan and NED deepened during the succeeding years, culminating in the creation of the TFD in 2003. But history had returned with a vengeance on 9/11, and the world entered a much darker period marked by 17 consecutive years of decline in global freedom, according to the Freedom House annual survey. There were many reasons for democracy’s setbacks, among them the war on terror that fostered tightened government restrictions everywhere, the global financial crisis in 2008 that undermined the confidence and stature of the world’s established democracies, the backsliding of many new democracies like Hungary and Venezuela, and the rise of illiberal populism. But nothing contributed more to the democratic retreat than the resurgence of the world’s leading authoritarian countries, the most important of them being China.

The cooperation between Taiwan and NED deepened during the succeeding years, culminating in the creation of the TFD in 2003. But history had returned with a vengeance on 9/11, and the world entered a much darker period marked by 17 consecutive years of decline in global freedom, according to the Freedom House annual survey. There were many reasons for democracy’s setbacks, among them the war on terror that fostered tightened government restrictions everywhere, the global financial crisis in 2008 that undermined the confidence and stature of the world’s established democracies, the backsliding of many new democracies like Hungary and Venezuela, and the rise of illiberal populism. But nothing contributed more to the democratic retreat than the resurgence of the world’s leading authoritarian countries, the most important of them being China.

Liu Xiaobo had warned prophetically in 2006, at the very beginning of this democratic decline, that China’s rise as a dictatorship would be a “catastrophe for the Chinese people” and “a disaster for the spread of liberal democracy in the world.” Nobody listened to him because the West fully supported the PRC’s spectacular economic growth, believing that it would promote the China’s liberalization. As we know, though, it had the opposite effect of reinforcing the regime’s belief in the superiority of its state-driven economic model while also financing a parallel buildup in military spending that has grown nearly five-fold in the last two decades.

Beijing fed the Western penchant for self-delusion about its intentions by following Deng Xiaoping’s dictum to hide its strength and bide its time. But when Xi Jinping took over a decade ago, he threw caution to the winds and immediately adopted a far more confrontational policy toward the U.S. and other countries that he called “the great rejuvenation.” In addition to restoring strongman rule, radically centralizing power, tightening repression, and imposing a comprehensive system of digital surveillance, the PRC launched vast infrastructure and development projects to expand Beijing’s influence in the Global South; took aggressive actions in the South and East China Seas that alarmed its Asian neighbors; formed a “no limits” strategic partnership with Russia just weeks before Putin invaded Ukraine; and repeatedly conducted menacing military exercises and cyberattacks targeting Taiwan. On the 100th anniversary of the CCP in 2021, Xi drove home how much more bellicose the PRC had become when he warned that anyone who dared to bully China “will find their heads bashed against a great wall of steel forged by over 1.4 billion Chinese people.”

Beijing fed the Western penchant for self-delusion about its intentions by following Deng Xiaoping’s dictum to hide its strength and bide its time. But when Xi Jinping took over a decade ago, he threw caution to the winds and immediately adopted a far more confrontational policy toward the U.S. and other countries that he called “the great rejuvenation.” In addition to restoring strongman rule, radically centralizing power, tightening repression, and imposing a comprehensive system of digital surveillance, the PRC launched vast infrastructure and development projects to expand Beijing’s influence in the Global South; took aggressive actions in the South and East China Seas that alarmed its Asian neighbors; formed a “no limits” strategic partnership with Russia just weeks before Putin invaded Ukraine; and repeatedly conducted menacing military exercises and cyberattacks targeting Taiwan. On the 100th anniversary of the CCP in 2021, Xi drove home how much more bellicose the PRC had become when he warned that anyone who dared to bully China “will find their heads bashed against a great wall of steel forged by over 1.4 billion Chinese people.”

The PRC’s aggressiveness has caused many analysts to conclude that a new Cold War has begun between China and the U.S. The Biden Administration acknowledged as much, at least implicitly, when it asserted in its latest National Security Strategy that “the post-Cold War era is definitively over and a competition is underway between the major powers to shape what comes next.” I’m aware that there are many differences between this new Cold War and the old one, not the least of which is that China is far wealthier and more integrated into the global economy than the Soviet Union ever was. But recognizing that this new stage of global geopolitics has much in common with the Cold War has the advantage of providing a framework for analyzing what needs to be done to counter a “rejuvenated” China. While highlighting the dangers we face, it should also remind us, in the way the Cold War ended, that there’s light at the end of the tunnel, but only if we have the wisdom and political will to take the actions that are needed to preserve peace and security and deter aggression.

In the short time I have left, I want to briefly sketch out the three basic policy concepts that guided the West during the Cold War that all remain relevant today in defending Taiwan, which is the epicenter of the U.S.-China confrontation.

In the short time I have left, I want to briefly sketch out the three basic policy concepts that guided the West during the Cold War that all remain relevant today in defending Taiwan, which is the epicenter of the U.S.-China confrontation.

The first is the concept of containment that was carried out through a comprehensive and vigilant policy of military deterrence designed to prevent Soviet expansion and to keep the Cold War from turning hot. The second is the concept of mellowing, the term George Kennan used in his famous X article in Foreign Affairs to describe the process by which the inherent flaws in the closed Soviet system would gradually erode the regime’s ability to maintain absolute control. The third is the battle of ideas, which is the political and ideological competition between democratic and totalitarian systems. This last area is where institutions the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy and NED can play a unique role.

Regarding the first concept of containment, I note that when Matt Pottinger visited Taiwan last month, he said that the formula of effective deterrence to safeguard Taiwan’s security is “capability times credibility.” He highlighted the urgent importance of deterrence in a recent Foreign Affairs article (co-authored with John Pomfret) in which he warned that Xi Jinping should be taken seriously when he said in four separate speeches last March to the National People’s Congress and its political advisory body that China is preparing for war to conquer Taiwan and thereby “complete reunification.” It’s widely believed – including by Taiwan’s Foreign Minister Joseph Wu – that the PRC could launch this aggression by 2027 when it will have completed its military modernization program. The time has come, therefore, for Taiwan and its principal allies, the United States and Japan, to urgently accelerate efforts to build the capability to repel and defeat a Chinese aggression, which is the best way to prevent it from happening in the first place. That’s the goal of deterrence.

What needs to be done – and why it must be done without delay – is spelled out in a recent article co-authored by our friend Larry Diamond and Admiral James O. Ellis, the commander of the aircraft carrier battle group that led the successful U.S. response to the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis in 1996. A central point of their analysis is that deterring PRC aggression against Taiwan is more than a moral issue of defending a small democracy against a much larger totalitarian state. They emphasize that defense of Taiwan is a vital security interest for the U.S., and that Japanese defense strategists increasingly believe that an attack on Taiwan would pose an existential threat to the security of Japan. Existential is a word that Diamond and Ellis frequently use, since they strongly believe that the subjugation of Taiwan would have devastating consequences for the future of peace and democracy in the world, something that is often overlooked in talking about the danger facing Taiwan. It would shatter U.S. credibility throughout the Indo-Pacific and beyond. It would give China control of not just the South and East China Seas, the sea lanes through which a third of global trade passes, but also of Taiwan’s strategically vital semi-conductor industry on which the U.S., Japanese, and European economies heavily depend. Perhaps most dangerously, it would enable the PRC to transform Taiwan into a huge military platform from which it could project power in all directions – northward towards Japan and South Korea, southward to the Philippines and other countries in Southeast Asia, and eastward towards the Pacific Island states. The conquest of Taiwan, in other words, would give the PRC the power to Finlandize Japan and other countries in Asia, and possibly European countries as well. Finlandization, for those who may not know the word, is a Cold War term signifying the ability of a powerful dictatorship to force its will on weaker countries.

What needs to be done – and why it must be done without delay – is spelled out in a recent article co-authored by our friend Larry Diamond and Admiral James O. Ellis, the commander of the aircraft carrier battle group that led the successful U.S. response to the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis in 1996. A central point of their analysis is that deterring PRC aggression against Taiwan is more than a moral issue of defending a small democracy against a much larger totalitarian state. They emphasize that defense of Taiwan is a vital security interest for the U.S., and that Japanese defense strategists increasingly believe that an attack on Taiwan would pose an existential threat to the security of Japan. Existential is a word that Diamond and Ellis frequently use, since they strongly believe that the subjugation of Taiwan would have devastating consequences for the future of peace and democracy in the world, something that is often overlooked in talking about the danger facing Taiwan. It would shatter U.S. credibility throughout the Indo-Pacific and beyond. It would give China control of not just the South and East China Seas, the sea lanes through which a third of global trade passes, but also of Taiwan’s strategically vital semi-conductor industry on which the U.S., Japanese, and European economies heavily depend. Perhaps most dangerously, it would enable the PRC to transform Taiwan into a huge military platform from which it could project power in all directions – northward towards Japan and South Korea, southward to the Philippines and other countries in Southeast Asia, and eastward towards the Pacific Island states. The conquest of Taiwan, in other words, would give the PRC the power to Finlandize Japan and other countries in Asia, and possibly European countries as well. Finlandization, for those who may not know the word, is a Cold War term signifying the ability of a powerful dictatorship to force its will on weaker countries.

Given the enormity of the global stakes involved, Taiwan will not be alone in trying to deter the PRC. Diamond and Ellis recommend many specific steps that the U.S. and Japan need to take to ramp up their military capabilities and increase joint training and exercises with Taiwan, while also making clear to Beijing the enormous risk it would be taking in attacking Taiwan. But they also stress that Taiwan cannot assume that the U.S. and Japan alone will be able to deter China from aggression. For deterrence to be effective, Taiwan will have to convince the PRC that it “will mount a fierce, determined, and creative resistance (in the spirit of Ukraine) that will enable it to hold out until support arrives from the United States and its allies.” This will require a rapid transition to an asymmetric fighting force of small, mobile, and survivable systems that could effectively resist airborne and amphibious invasion. It will also require Taiwan to amass stockpiles of weapons and critical resources, above all energy, in the event the PRC tries to strangle it into submission with a naval blockade.

Given the enormity of the global stakes involved, Taiwan will not be alone in trying to deter the PRC. Diamond and Ellis recommend many specific steps that the U.S. and Japan need to take to ramp up their military capabilities and increase joint training and exercises with Taiwan, while also making clear to Beijing the enormous risk it would be taking in attacking Taiwan. But they also stress that Taiwan cannot assume that the U.S. and Japan alone will be able to deter China from aggression. For deterrence to be effective, Taiwan will have to convince the PRC that it “will mount a fierce, determined, and creative resistance (in the spirit of Ukraine) that will enable it to hold out until support arrives from the United States and its allies.” This will require a rapid transition to an asymmetric fighting force of small, mobile, and survivable systems that could effectively resist airborne and amphibious invasion. It will also require Taiwan to amass stockpiles of weapons and critical resources, above all energy, in the event the PRC tries to strangle it into submission with a naval blockade.

The scale and urgency of mounting a credible deterrence are so great that it would be easy to disregard the other two Cold War concepts I mentioned of mellowing and political competition. These concepts hold open the possibility that China can change over time, and encouraging such a process should remain part of a containment strategy, even if the prospect of a political opening in China may now seem far-fetched. It’s true that Xi seemed to have cemented his supreme power at the 20th Party Congress last October when he ended collective leadership and packed the Politburo and Standing Committee with his party loyalists. But as Minxin Pei noted at the time, that’s exactly what Mao did at the 9th Party Congress in 1969, leading to a brutal succession struggle, a devastated party, and a rival eventually taking power who introduced market-based reforms that Mao considered an abomination. Pei calls this an example of “the paradox of power,” which is the inverse relationship between the amount of power amassed by a strongman and the security of his rule. Unchecked power and seemingly absolute political supremacy, Pei writes, “may be a curse disguised as a blessing,” breeding political overreach, vicious factional battles, and debilitating governance dysfunction.

There are examples of the paradox of power in Chinese history that long predate the recent period of communist rule. When the NED held a discussion in 2021 on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the CCP, Perry Link said that the communist dynasty, as he called it, was one of three “violent paroxysms” in Chinese history, the other two being the Qin dynasty in the 3rd century BCE and the Sui dynasty almost 850 years later that shared a number of characteristics with the PRC. They centralized political power using violence to secure control; they maintained large armies that were deployed against neighboring states; they conscripted massive corvee labor to build ambitious construction projects like the Great Wall and the Grand Canal; they burned books and killed scholars; and, most importantly for the present discussion, they were short-lived. The underlying strength of Chinese civilization outlived both the Qin and Sui dynasties, Link said, and though the accessibility of Orwellian surveillance technologies gives the current communist dynasty an additional means of control unavailable to the Qin and Sui, Link said he believed that “the ethical foundations of Chinese civilization” would also outlive the CCP.

There are examples of the paradox of power in Chinese history that long predate the recent period of communist rule. When the NED held a discussion in 2021 on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the CCP, Perry Link said that the communist dynasty, as he called it, was one of three “violent paroxysms” in Chinese history, the other two being the Qin dynasty in the 3rd century BCE and the Sui dynasty almost 850 years later that shared a number of characteristics with the PRC. They centralized political power using violence to secure control; they maintained large armies that were deployed against neighboring states; they conscripted massive corvee labor to build ambitious construction projects like the Great Wall and the Grand Canal; they burned books and killed scholars; and, most importantly for the present discussion, they were short-lived. The underlying strength of Chinese civilization outlived both the Qin and Sui dynasties, Link said, and though the accessibility of Orwellian surveillance technologies gives the current communist dynasty an additional means of control unavailable to the Qin and Sui, Link said he believed that “the ethical foundations of Chinese civilization” would also outlive the CCP.

Frances Fukuyama noted recently that strongman rule is inherently precarious because “the concentration of power in the hands of a single leader at the top all but guarantees low-quality decision making, and over time will produce truly catastrophic consequences.” It still remains to be seen how catastrophic Xi’s errors have been, but it’s already been significant. At a time of economic slowdown and record youth unemployment, he launched a systematic crackdown on the private sector that accounts for two-thirds of China’s economy, targeting especially the big tech firms like Alibaba and Tencent and leading to a $2 trillion plunge in the market value of Chinese companies listed overseas, all for the purpose of strengthening the CCP’s control of the economy. His belligerent assertion of Chinese power abroad has provoked a backlash that has driven the U.S. and Japan closer together and has been responsible for the deepening of security ties between Asia and Europe, as demonstrated by the attendance at the NATO summit last week of the Asia Pacific Partners (AP4), a new union of Asian democracies.

As bad as these and other policy failures have been, they don’t compare with Xi’s disastrous management of the pandemic. The drastic lockdowns associated with the zero-COVID policy triggered the largest protests since the Tiananmen uprising in 1989. Even worse was the sudden lifting right after those protests in December of all COVID restrictions without any preparations whatsoever – no vaccinations or stocking up hospitals and drug stores, nothing – leading to as many as two million deaths and virtually the entire society contracting the disease. The impact in China of this catastrophe is still not fully understood, but it goes beyond the terrible suffering and the deaths.

As bad as these and other policy failures have been, they don’t compare with Xi’s disastrous management of the pandemic. The drastic lockdowns associated with the zero-COVID policy triggered the largest protests since the Tiananmen uprising in 1989. Even worse was the sudden lifting right after those protests in December of all COVID restrictions without any preparations whatsoever – no vaccinations or stocking up hospitals and drug stores, nothing – leading to as many as two million deaths and virtually the entire society contracting the disease. The impact in China of this catastrophe is still not fully understood, but it goes beyond the terrible suffering and the deaths.

In that regard, I call your attention to a podcast interview with David Ownby, a professor at the University of Montreal who runs the Reading the China Dream website that has published for the past five years English translations of the writings of scores of mainstream Chinese intellectuals, from liberals and New Confucians to the highly statist New Left. He met with many of these intellectuals when he visited Beijing and Shanghai in May, and what he discovered, much to his surprise, was a profound and pervasive sense of disillusionment and anger at the incompetence and utter cynicism of the government. Almost everyone he spoke with – the only exception being a dinner he had with some New Left “celebrities,” as he called them – felt that the way zero COVID ended had upset their lives and even “marked their souls” in ways they couldn’t get over, even though the abrupt ending had happened six months earlier. It was as if they were in mourning, Ownby said. As a young journalist said to him, “You’d like to think your government cares a little about you, but no. I have to rethink everything I thought I knew.” Ownby said that these intellectuals were not alone in their visible fury and alienation from the system. When he said to a professor he was having lunch with that it seemed as if millions of Chinese were experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder and were like “walking time bombs,” the professor said “Yep, that’s pretty much it. Everyone in this room, at some level, is living that.” Ownby said that it was too early to know if this was a turning point in China, but he felt that it was definitely “an existential crisis.”

It’s clear that the situation in China has changed drastically since the early days of the pandemic when Xi and his wolf warriors boasted about how superior their centrally directed system was to messy democracy. The idea of authoritarian proficiency doesn’t sell as well today, and it’s not just because of the calamitous consequences for Russia of Putin’s genocidal invasion of Ukraine and the mass protests that have shaken Iran since the killing last September of Mahsa Amini for the crime of not wearing a hijab. The idea of authoritarian competence has now been thoroughly trashed in China as well, and so this may be a propitious moment to pursue that third Cold War concept of the battle of ideas.

It’s clear that the situation in China has changed drastically since the early days of the pandemic when Xi and his wolf warriors boasted about how superior their centrally directed system was to messy democracy. The idea of authoritarian proficiency doesn’t sell as well today, and it’s not just because of the calamitous consequences for Russia of Putin’s genocidal invasion of Ukraine and the mass protests that have shaken Iran since the killing last September of Mahsa Amini for the crime of not wearing a hijab. The idea of authoritarian competence has now been thoroughly trashed in China as well, and so this may be a propitious moment to pursue that third Cold War concept of the battle of ideas.

It’s the responsibility of the TFD and others in Taiwan to figure out how to do this. But I do think that a quiet dialogue with some of the intellectuals who are published on Ownby’s website would be useful, and it would also be important to talk with some Chinese entrepreneurs. Ownby said the intellectuals he knows like to get out of the confines of the university and speak with entrepreneurs whom they find extremely informed and interesting since they’ve been fighting their battles in the real world for many years and know how the system works.

As intellectuals and others in China try to recover from the current moral crisis and think through an alternative to Xi’s China Dream, which is just a warmed-over version of Maoism, there is nothing more important that Taiwan can do than to remain a model of freedom and democratic governance. One of the very first things that Xi did when he took power in 2012 was to issue the communique called Document No. 9 to “conscientiously strengthen management of the ideological battlefield.” It directed party cadres to intensify the struggle against political “perils” like constitutional government, civil society, universal values, and free media – all core principles of liberal democracy. The communique repeatedly referred to these principles as Western and warned against their “infiltration” into Chinese society, something Xi clearly worried about. Taiwan’s democracy shows that these principles are perfectly compatible with Confucian culture and are, in fact, truly universal. This is a powerful message to be carrying, a different kind of dream that has the potential to capture the imagination of the Chinese people. At a time of great danger, it is a source of hope.

As intellectuals and others in China try to recover from the current moral crisis and think through an alternative to Xi’s China Dream, which is just a warmed-over version of Maoism, there is nothing more important that Taiwan can do than to remain a model of freedom and democratic governance. One of the very first things that Xi did when he took power in 2012 was to issue the communique called Document No. 9 to “conscientiously strengthen management of the ideological battlefield.” It directed party cadres to intensify the struggle against political “perils” like constitutional government, civil society, universal values, and free media – all core principles of liberal democracy. The communique repeatedly referred to these principles as Western and warned against their “infiltration” into Chinese society, something Xi clearly worried about. Taiwan’s democracy shows that these principles are perfectly compatible with Confucian culture and are, in fact, truly universal. This is a powerful message to be carrying, a different kind of dream that has the potential to capture the imagination of the Chinese people. At a time of great danger, it is a source of hope.

Authoritarian regimes are working to “corrode our democratic institutions and undermine human rights” in an attempt to sow doubt in society and erode people’s confidence in democracy, #Taiwan‘s President @iingwen told the @TFDemocracy anniversary. https://t.co/4DuXbd1KZZ

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) July 18, 2023