Besieged by Russian propaganda, Lithuanians are using software to fight back against fake news, the Economist reports. Demaskuok, which means “debunk” in Lithuanian, is a piece of software that searches for the patient zeros of fake news. It was developed by Delfi, a media group headquartered in Lithuania’s capital, Vilnius, in conjunction with Google..Demaskuok identifies its suspects in many ways:

Besieged by Russian propaganda, Lithuanians are using software to fight back against fake news, the Economist reports. Demaskuok, which means “debunk” in Lithuanian, is a piece of software that searches for the patient zeros of fake news. It was developed by Delfi, a media group headquartered in Lithuania’s capital, Vilnius, in conjunction with Google..Demaskuok identifies its suspects in many ways:

- One is to search for wording redolent of themes propagandists commonly exploit. These include poverty, rape, environmental degradation, military shortcomings, war games, societal rifts, viruses and other health scares, political blunders, poor governance, and, ironically, the uncovering of deceit. And because effective disinformation stirs the emotions, the software gauges a text’s ability to do that, too. …

- Another clue is that disinformation is crafted to be shared. Demaskuok therefore measures “virality”—the number of times readers share or write about an item. The reputations of websites that host an item or provide a link to it provide additional information. The software even considers the timing of a story’s appearance. Fake news is disproportionately posted on Friday evenings when many people, debunkers included, are out for drinks.

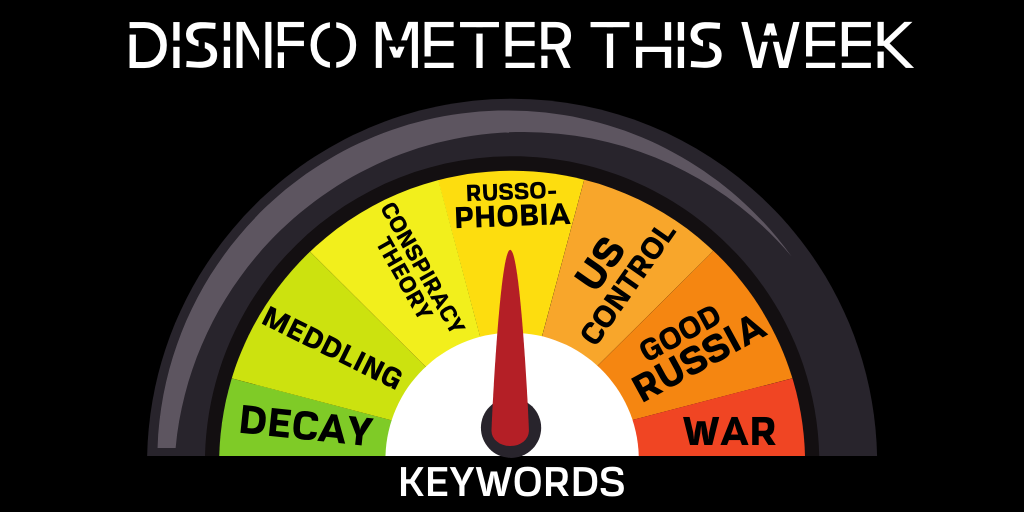

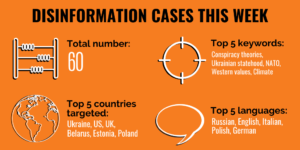

To make sense of 60 cases of Russian disinformation gathered this week, the East Stratcom Task Force divided the most common and recurring narratives into broader categories (above). The overarching thrust of the Kremlin’s messaging is how the rotting West is an enemy led by a small clique of evildoers, like George Soros. By using different instruments like NATO, the West is meddling all over the world and threatens Russia politically, culturally, and militarily.

To make sense of 60 cases of Russian disinformation gathered this week, the East Stratcom Task Force divided the most common and recurring narratives into broader categories (above). The overarching thrust of the Kremlin’s messaging is how the rotting West is an enemy led by a small clique of evildoers, like George Soros. By using different instruments like NATO, the West is meddling all over the world and threatens Russia politically, culturally, and militarily.

Democracies like the United States are ill-equipped to counter new forms of conflict emanating from autocratic states such as Russia, China and Iran, argues Sean McFate, a professor at the National Defense University and Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service, and author of The New Rules of War.

“I would implement strategies across the globe that utilize and harness the new rules of war for us. They’re all doing it: Russia, China, Iran… They’re all fighting these things called shadow wars, and they’re very effective. We need to get back in that. And we used to do this during the Cold War, but we’ve forgotten how,” he tells MIT Technology Review:

“I would implement strategies across the globe that utilize and harness the new rules of war for us. They’re all doing it: Russia, China, Iran… They’re all fighting these things called shadow wars, and they’re very effective. We need to get back in that. And we used to do this during the Cold War, but we’ve forgotten how,” he tells MIT Technology Review:

Q: What is a shadow war? How would you describe it?

A: Shadow wars are a certain type of war where plausible deniability eclipses firepower in terms of effectiveness. Think about how Russia was in Crimea. In older war tactics, when they would put their heel on another state, they’d send in the tanks. Now, in 2019, that’s not how they do it. They have military backup, but they use covert and clandestine means. They use special forces, they use mercenaries, they use proxies, they use propaganda—things that give them plausible deniability. They manufacture the fog of war and then exploit it for victory.

McFate describes a shift from wars between states to wars within states, strategist Lawrence Freedman wrote for Foreign Affairs. Great powers pursue their interests by using whatever nonmilitary tools are available, from social media to trade, and try to avoid serious fighting. Nonstate actors, on the other hand, use whatever weapons they can get their hands on.

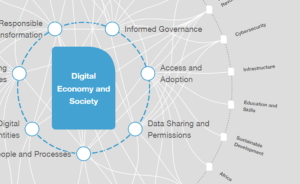

Over 2,500 years after the birth of democracy in Ancient Greece, and just a few hundred years after its resurgence at the end of the medieval times, we are transitioning into a ‘digital democracy’, the Observer Research Foundation’s Lydia Kostopoulos notes. We are toddlers in this new period, learning how to walk in the digital spaces of an intangible territorial sovereignty, where the digital borders are blurry but play a role on the democratic infrastructure inside physical borders, she writes in Interrogating the future of digital democracies:

Over 2,500 years after the birth of democracy in Ancient Greece, and just a few hundred years after its resurgence at the end of the medieval times, we are transitioning into a ‘digital democracy’, the Observer Research Foundation’s Lydia Kostopoulos notes. We are toddlers in this new period, learning how to walk in the digital spaces of an intangible territorial sovereignty, where the digital borders are blurry but play a role on the democratic infrastructure inside physical borders, she writes in Interrogating the future of digital democracies:

Digital technologies, combined with the pervasiveness of corporate algorithms, have created a social and economic infrastructure that has increasingly taken power away from government as more citizens sign onto terms and conditions of the platforms they digitally inhabit. ..However, as the spaces we inhabit (with our attention) have shifted from physical to digital, we have entered the sovereignty of those digital spaces, and their respective algorithms, which have increasingly become the mediators of our lives. They suggest who to date, what job to apply to, what home appliance to buy and which political candidate to vote for.