Moral and cultural organisations must strive harder to rid the body politic of populist infection, in central Europe and elsewhere, says Tomáš Halík, a professor of sociology at Charles University in Prague. The most important knowledge to be derived from the study of post-communist society in eastern Europe is that when it comes to building democracy the establishment of parliaments, political parties and a free press is the easy part.

Moral and cultural organisations must strive harder to rid the body politic of populist infection, in central Europe and elsewhere, says Tomáš Halík, a professor of sociology at Charles University in Prague. The most important knowledge to be derived from the study of post-communist society in eastern Europe is that when it comes to building democracy the establishment of parliaments, political parties and a free press is the easy part.

If democracy is to thrive, it needs a certain level of education and critical thinking, and a moral climate of mutual respect among citizens. Democracy is not simply a political system; it is a culture of human relations, he writes for the THES:

For a while, we thought that the crisis of confidence in democracy in central and eastern Europe was a result of the importance of civil society being overlooked when states were rebuilt after the fall of communism. This is certainly true, but “democracy fatigue” is also spreading in countries with lengthy unbroken traditions of democracy. …

In a society oriented much more towards the individual than towards social cohesiveness, the individual eventually feels lost and isolated. The weakening of the family in particular means that many people fail to create their own identity. As a result, they easily become attached to groups that offer a strong sense of group identity, often boosted by the demonization of the outside world.

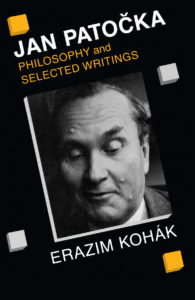

Anti-Communist dissidents such as Jan Patocka and Andrei Sakharov understood that totalitarian rule was based on fear. Similarly, illiberal populism thrives on stoking fear and anxiety about the Other.

His article is based on a keynote address he gave at Times Higher Education’s Research Excellence: New Europe Summit in April at Palacký University Olomouc, Czech Republic.