Vladimir Putin doesn’t tweet and he claims he doesn’t have a smartphone. But he has something likely more important than gadgets — long experience in the KGB and its post-Soviet successor, notes AP’s Jim Heintz. From the czarist secret police to the present, Russian operatives have adroitly exploited humans’ biases and their capacity to believe the unlikely. The elaborate campaign of bogus identities and inflammatory statements alleged in last week’s U.S. indictment of 13 Russians used new technology and platforms, but drew on a century-old spirit, he writes for The Washington Post:

Vladimir Putin doesn’t tweet and he claims he doesn’t have a smartphone. But he has something likely more important than gadgets — long experience in the KGB and its post-Soviet successor, notes AP’s Jim Heintz. From the czarist secret police to the present, Russian operatives have adroitly exploited humans’ biases and their capacity to believe the unlikely. The elaborate campaign of bogus identities and inflammatory statements alleged in last week’s U.S. indictment of 13 Russians used new technology and platforms, but drew on a century-old spirit, he writes for The Washington Post:

An early and especially notorious example was the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a pamphlet that purported to be the minutes of a secret meeting of Jewish leaders to plot world domination. First appearing in 1903, its origins are open to debate, but many scholars suggest it was commissioned by Okhranka, the czarist secret police, and spread by them to argue against growing calls for modernizing Russia.

Russia’s disinformation efforts and other active measures raise worries about the vulnerabilities of Western democracies and American special counsel Robert Mueller’s indictments hold three uncomfortable lessons, The Economist notes:

Russia’s disinformation efforts and other active measures raise worries about the vulnerabilities of Western democracies and American special counsel Robert Mueller’s indictments hold three uncomfortable lessons, The Economist notes:

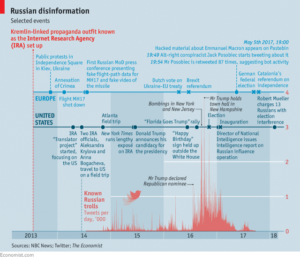

- One is that social media are a more potent tool than the 1960s techniques of planting stories and bribing journalists. It does not cost much to use Facebook to spot sympathisers, ferret out potential converts and perfect the catchiest taglines (see article). …With a modest budget, of a little over $1m a month, and working mostly from the safety of St Petersburg, the Russians managed botnets and false profiles, earning millions of retweets and likes. Other, better-funded, groups exploit similar techniques. Nobody yet knows how the outrage they generate changes politics, but it is a fair guess that it deepens partisanship and limits the scope for compromise.

- Hence the second lesson, that the Russia campaign did not create divisions in America so much as hold up a warped mirror to them. ….Europeans are to a lesser degree divided, too, especially in Brexit Britain. The divisions that run so deep within Western democracies leave them open to intruders.

- The most important lesson is that the Western response has been woefully weak. In the cold war, America fought Russian misinformation with diplomats and spies. By contrast, Mr Mueller acted because two presidents fell short.

A bipartisan effort is required to combat Russia’s efforts to undermine democracy, according to Robert D. Blackwill and Philip H. Gordon, senior fellows at the Council on Foreign Relations and authors of a new special report called “Containing Russia.” As two former executive branch officials, we are hardly instinctive proponents of Congress taking the lead on foreign policy. But these are extraordinary times that require extraordinary measures, they write for The Hill:

A bipartisan effort is required to combat Russia’s efforts to undermine democracy, according to Robert D. Blackwill and Philip H. Gordon, senior fellows at the Council on Foreign Relations and authors of a new special report called “Containing Russia.” As two former executive branch officials, we are hardly instinctive proponents of Congress taking the lead on foreign policy. But these are extraordinary times that require extraordinary measures, they write for The Hill:

The first thing Congress needs to do is to conduct rigorous oversight to ensure enforcement of the Russia sanctions it authorized overwhelmingly last summer. The Confronting America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act expanded cyber sanctions, extended restrictions on Russian energy firms, and added to the list of sanctionable sectors of the Russian economy.

It’s clear that one of the most profound yet insidious threats to democracy now comes from authoritarian states engaging in subversive activities in and against our nations, says Robert Seely MP, who sits on the UK Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Select Committee.

“As part of my academic work, I’ve developed a simple but comprehensive framework for understanding these new forms of ‘full spectrum’ Russian conflict, he writes for The SMH:

….hard power (military: conventional and non-conventional), soft power (governance, law and culture), subversive political power (hacking, assassinations, use of proxies and front groups, blackmail), economic power (tariffs, energy supplies, criminality), information power (online and offline information campaigns), and diplomacy and public outreach (everything from biker gangs to espionage). These are wrapped around command and control functions – which we need to identify because we need to know who is pulling the strings. Within these areas are at least 50 individual tools and techniques so far identified. These are the new weapons –  online and offline – of conflict, influence and interference. [Perhaps it’s time to add what a National Endowment for Democracy report calls Sharp Power too.]

online and offline – of conflict, influence and interference. [Perhaps it’s time to add what a National Endowment for Democracy report calls Sharp Power too.]

“One of the key characteristics of Russian operations is that they are holistic,” Seely adds. “Therefore our response needs to be holistic too.”

In an age when most people get their news from social media, mafia states have had little trouble censoring social-media content that their leaders deem harmful to their interests, says Guy Verhofstadt, a former Belgian prime minister, and President of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Group (ALDE) in the European Parliament. But for liberal democracies, regulating social media is not so straightforward, because governments must strike a balance between competing principles, he writes for Project Syndicate:

To be sure, censorship and the manipulation of information are as old as news itself. But the kind of state-sponsored hybrid warfare on display today is something new. Hostile powers have turned our open Internet into a cesspool of disinformation, much of which is spread by automated bots that the major platforms could purge without undermining open debate – that is, if they had the will to do so.