A few years ago the US academic Larry Diamond declared that a “democratic recession” had set in after about 2006. The long global expansion of democracy that began with the fall of the Soviet Union faltered. Worse, it then started to reverse, notes analyst Peter Hartcher:

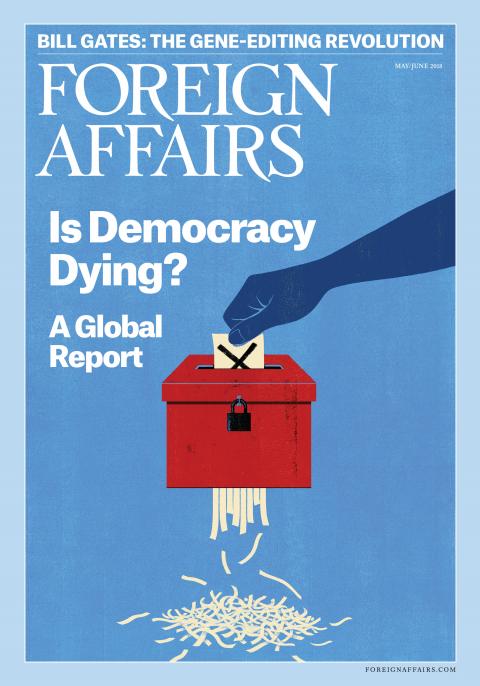

If it was a recession then, it’s full-blown depression today. A Washington-based watchdog, Freedom House, this year titles its annual assessment of the state of freedom in all the countries of the world “Democracy in Crisis”. Its opening sentence: “Democracy faced its most serious crisis in decades in 2017 as its basic tenets – including guarantees of free and fair elections, the rights of minorities, freedom of the press, and the rule of law – came under attack around the world.” The cover of the current issue of the US journal Foreign Affairs goes so far as to wonder: “Is democracy dying?”

It is too easy for political theorists to forget that all political regimes exist in time, they are historical. No political form is eternal, notes Aviezer Tucker, the author of The Legacies of Totalitarianism: A Theoretical Framework.

It is too easy for political theorists to forget that all political regimes exist in time, they are historical. No political form is eternal, notes Aviezer Tucker, the author of The Legacies of Totalitarianism: A Theoretical Framework.

Liberal democracy is no exception, but a historically hard-won achievement, something rare and built up only over a long time; it doesn’t have an “instant” formula that admirers can assemble in a quick do-it-yourself manner for export or import, he writes for the American Interest:

Liberal democracies with young and brittle stems and shallower and weaker roots in a hard, dry, and unforgiving historical soil as in Hungary and Poland can be uprooted and blow away when the economic winds change. Democracies with the deepest roots, as in Britain and its former colonies, where institutions and attitudes have come to align most closely, are the most difficult to uproot. Demagogues can shake them, yet they remain rooted.

The fundamental cause of so-called decline of democracies is failed and failing government, according to analyst Harlan Ullman. Whether in the United States or other states around the world, governments are not providing their public acceptable levels of governance.

The fundamental cause of so-called decline of democracies is failed and failing government, according to analyst Harlan Ullman. Whether in the United States or other states around the world, governments are not providing their public acceptable levels of governance.

Declinism is in fashion, notes Edmund Fawcett, the author of ‘Liberalism: The Life of an Idea.’ But the flaws and follies of declinism are easy to spot, he writes for the FT:

Declinism is unoriginal, speaks in sermony tones and has sloppy intellectual habits. True enough, but the deeper trouble is that it’s a distraction. Declinism appeals to speculative trends we can’t be sure about and a future we can’t see. Its scarifications distract us from urgent repairs needed for democratic liberalism here and now.

Declinism is unoriginal, speaks in sermony tones and has sloppy intellectual habits. True enough, but the deeper trouble is that it’s a distraction. Declinism appeals to speculative trends we can’t be sure about and a future we can’t see. Its scarifications distract us from urgent repairs needed for democratic liberalism here and now.

There is no inevitable march of progress in history or law. Everything that has been achieved can be rescinded, forgotten, tossed away. That is the message Oona Hathaway and Scott Shapiro want to convey in The Internationalists, notes Cornell University’s Isabel Hull.

Hathaway and Shapiro’s premise is that since states seemed incapable of weaning themselves off warfare, civil society had to intervene. They focus on four ‘internationalists’ who helped broker, institutionalize and interpret the Kellogg-Briand Pact, she writes for the London Review of Books. The book is a timely and necessary plea for international law and for the value of institutions from which we all have benefited, but which we have in recent decades neglected to explain or defend.

Hathaway and Shapiro’s premise is that since states seemed incapable of weaning themselves off warfare, civil society had to intervene. They focus on four ‘internationalists’ who helped broker, institutionalize and interpret the Kellogg-Briand Pact, she writes for the London Review of Books. The book is a timely and necessary plea for international law and for the value of institutions from which we all have benefited, but which we have in recent decades neglected to explain or defend.

“There’s a strong sense that dark times are upon us again, that democracy is in crisis, that the West is imploding,” says Sydney University political scientist John Keane.

“Crises are always lived, and that means they are always a matter of perception and interpretation. If, in time, millions of people come to think it’s a crisis, it’s a crisis,” counsels Keane.

The outcome is not predetermined, in other words. The leaders in the democratic world and, indeed, their followers, need to improve the objective living conditions of their people, Hartcher adds.