The coronavirus has given rise to a flood of conspiracy theories, disinformation and propaganda, eroding public trust and undermining health officials in ways that could elongate and even outlast the pandemic, the New York Times reports:

The coronavirus has given rise to a flood of conspiracy theories, disinformation and propaganda, eroding public trust and undermining health officials in ways that could elongate and even outlast the pandemic, the New York Times reports:

Many false claims are also being promoted by governments looking to hide their failures, partisan actors seeking political benefit, run-of-the-mill scammers and, in the United States, a president who has pushed unproven cures and blame-deflecting falsehoods. The conspiracy theories all carry a common message: The only protection comes from possessing the secret truths that “they” don’t want you to hear.

“We’ve faced pandemics before,” said Graham Brookie, who directs the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab. “We haven’t faced a pandemic at a time when humans are as connected and have as much access to information as they do now.”

Wikipedia

The coronavirus has highlighted the vulnerability that global value chains (GVCs) present when non-democracies exploit the rule-of-law cooperation that underpins them, note analysts Marcus Kolga, Kaveh Shahrooz and Shuvaloy Majumdar. China, for example, has steadily climbed the medical device GVC as a result of their Made-in-China 2025 policy. One of China’s goals is to transition from being on the low-value-added end to the high-value-added end of the GVC in 10 manufacturing sectors, including medical devices.

Authoritarians have become masters at subverting the postwar democratic order, while democracies have confused pluralism with moral relativism and equivocation, they write for MacLeans. Canada should now take the lead in promoting a democratic national interest that boldly strengthens the bonds between new and established democracies, and that builds resilience in vulnerable democracies.

Repressive regimes have responded to the pandemic in ways that serve their political interests, often at the expense of public health and basic freedoms. Even open societies face pressure to accept restrictions that may outlive the crisis and have a lasting effect on liberty, notes Freedom House, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

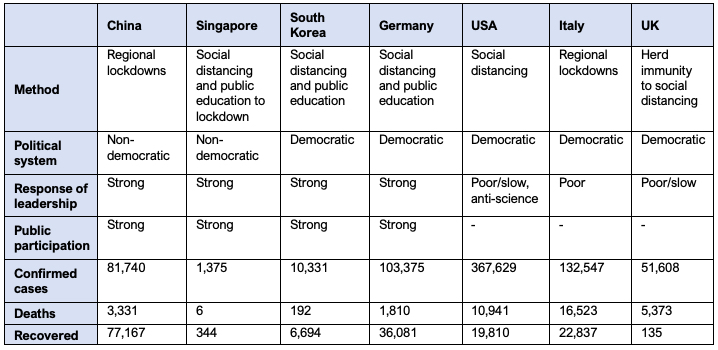

It is clear that the success or failure of a country in responding to the COVIS-19 pandemic does not depend on the type of regime (democratic or authoritarian) or type of policies implemented (partial or complete lockdowns), argues Dr Robertus Robet, a visiting scholar at the University of Melbourne (see table above):

It is clear that the success or failure of a country in responding to the COVIS-19 pandemic does not depend on the type of regime (democratic or authoritarian) or type of policies implemented (partial or complete lockdowns), argues Dr Robertus Robet, a visiting scholar at the University of Melbourne (see table above):

- Countries that responded successfully to the pandemic all had responsive political leaders. The quicker the leader recognised and responded to coronavirus as a serious threat, the better the management.

- Second, the presence of trusted medical authorities and strong public health policy has been critical to holding back spread.

- The third key factor has been strong public awareness and participation. Mutual trust between citizens and the government will promote rationality and voluntary adherence to social distancing and isolation policies.

The best outcome would be for the U.S. to pry open foreign markets with trade deals and for all advanced democracies to cooperate more extensively on health data and sharing critical supplies, even in emergencies, argues Charles Lipson, the Peter B. Ritzma Professor of Political Science Emeritus at the University of Chicago. The biggest impact, though, will be on China, as other nations recognize the costs imposed on them because of China’s secrecy and deception.

The best outcome would be for the U.S. to pry open foreign markets with trade deals and for all advanced democracies to cooperate more extensively on health data and sharing critical supplies, even in emergencies, argues Charles Lipson, the Peter B. Ritzma Professor of Political Science Emeritus at the University of Chicago. The biggest impact, though, will be on China, as other nations recognize the costs imposed on them because of China’s secrecy and deception.

Chinese authorities, keenly aware of the growing anger against the Chinese Communist Party, are pushing back against criticism, projecting themselves as heroes and shifting the blame, notes Helen Raleigh, the author of Confucius Never Said. Western democracies and social media companies should develop a coordinated strategy to counter Beijing’s propaganda campaign. If the West doesn’t forcefully respond, Beijing will feel even more emboldened to suppress freedom of expression—domestically and internationally, she writes for the City Journal.

Even at times of crisis like the coronavirus pandemic, democracies like the U.S. will outcompete autocracies like China for several reasons, argues Matthew Kroenig, professor of government and foreign service at Georgetown University.

Even at times of crisis like the coronavirus pandemic, democracies like the U.S. will outcompete autocracies like China for several reasons, argues Matthew Kroenig, professor of government and foreign service at Georgetown University.

Yes, democratic governments are obligated to answer to their citizens on regular intervals and are sensitive to public opinion—that’s actually democracies’ greatest source of strength, he writes for The Atlantic.

Democratic leaders have a harder time advancing big, bold agendas, but the upside of that difficulty is that the plans that do make it through the system have been carefully considered and enjoy domestic support. Historically speaking, once a democracy comes up with a successful strategy, it sticks with the plan, even through a succession of leadership…Washington has arguably followed the same basic, three-step geopolitical plan since 1945, he adds:

- First, the United States built the current, rules-based international system by providing security in important geopolitical regions, constructing international institutions, and promoting free markets and democratic politics within its sphere of influence.

- Second, it welcomed into the club any country that played by the rules, even former adversaries, like Germany and Japan.

- And, third, the U.S. worked with its allies to defend the system from those countries or groups that would challenge it, including competitors such as Russia and China, rogue states such as Iran and North Korea, and terrorist networks. RTWT