Freedom House

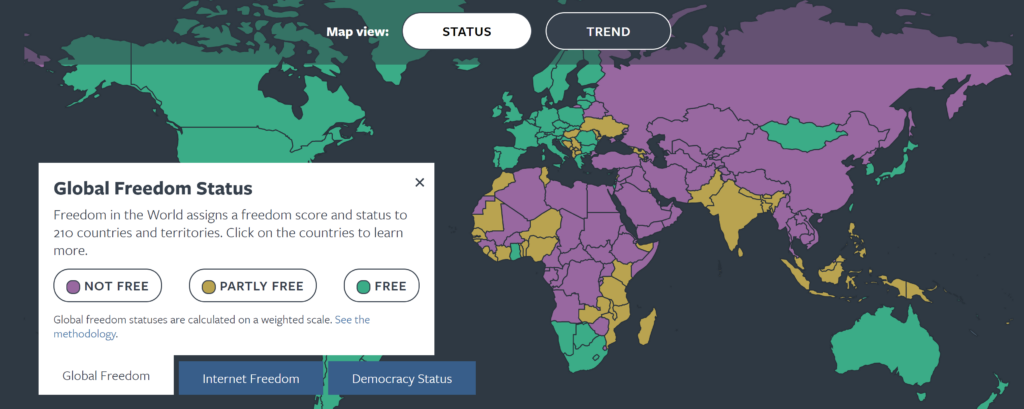

“The world’s long freedom recession may be bottoming out,” according to the latest Freedom House report. The 2022 survey found that global improvements in freedom nearly equaled global declines, researchers Yana Gorokhovskaia, Adrian Shahbaz, and Amy Slipowitz wrote for the Journal of Democracy.

But to assess whether the democratic recession is in fact starting to lift, it is necessary to go beyond simple scorecards and focus on what brought on the recession in the first place, says Thomas Carothers, co-director of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program. Democracy’s global retreat over the past decade and a half was the unfortunate confluence of three broad and deeply rooted negative global political developments, he contends:

At the heart of the democratic recession is the fact that many of the countries in the Global South and in the former communist world that attempted democratic transitions starting in the 1980s and 1990s—the core part of democracy’s “third wave”—have encountered serious problems in attempting to consolidate those changes. In some countries, such as Cambodia, Hungary, and Nicaragua, predatory political actors have amassed outsized amounts of political power, steamrollered relatively shallowly rooted democratic norms and institutions, and convinced a sizable share of populations disillusioned with the early results of democracy to go along for the illiberal ride. ….. It was almost inevitable that many of the third wave’s democratic experiments would run into rough sledding given that they were launched in contexts of profound institutional weaknesses, harsh socioeconomic realities, and thin experience with democratic practices and norms. But the falling short of prodemocratic aspirations has been wider and deeper than most observers—and, very importantly, most citizens of such countries—expected back when democracy seemed to be gaining global momentum.

At the heart of the democratic recession is the fact that many of the countries in the Global South and in the former communist world that attempted democratic transitions starting in the 1980s and 1990s—the core part of democracy’s “third wave”—have encountered serious problems in attempting to consolidate those changes. In some countries, such as Cambodia, Hungary, and Nicaragua, predatory political actors have amassed outsized amounts of political power, steamrollered relatively shallowly rooted democratic norms and institutions, and convinced a sizable share of populations disillusioned with the early results of democracy to go along for the illiberal ride. ….. It was almost inevitable that many of the third wave’s democratic experiments would run into rough sledding given that they were launched in contexts of profound institutional weaknesses, harsh socioeconomic realities, and thin experience with democratic practices and norms. But the falling short of prodemocratic aspirations has been wider and deeper than most observers—and, very importantly, most citizens of such countries—expected back when democracy seemed to be gaining global momentum.- Contributing to this widespread democratic malaise among newer democracies has been a second trend: an unexpectedly serious wave of democratic tremors hitting established wealthy democracies, the United States most sharply but many parts of Europe as well.

National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

This wave has been marked by widespread citizen alienation from conventional democratic institutions, including long-standing center-left and center-right parties, and the rise of illiberal right-wing parties and politicians. Powerful drivers have propelled these troubling political currents. These drivers have included long-term economic stagnation and rising insecurity of the middle class; illiberal counterreactions to progressive sociocultural change in domains such as immigration, ethnic and racial diversity, women’s rights, and LGBTQ rights; and the disruptive effects of technological change on the integrity of public information spaces and on basic societal cohesion. ….

- Adding still further to this troubled situation for global democracy in the first two decades of this century was the slow but ultimately deep authoritarian hardening of two crucial countries—China and Russia—that have gained the capacity and embraced the intent to challenge U.S. power and project antidemocratic practices and ideas widely beyond their borders. Other autocratic states, such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela, have also at different times and in different ways over the past fifteen years expanded efforts to influence the political trajectory of some of their neighbors, usually with antidemocratic intent and effects.

Recent reports gauging the global state of democracy make unpleasant reading:

Recent reports gauging the global state of democracy make unpleasant reading:

- The number of countries moving towards authoritarianism is more than double the number moving towards democracy, according to International IDEA.

- 37% of the world’s population lives under authoritarian rule, The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) observed.

- As much as 72% of the world’s population lives in autocracies, said the V-Dem Institute.

- Freedom House reported that only 43% of countries can be classified as free, a number equal to the percentage of states classified as democracies by the EIU.

Compared to 20 years ago, the number of autocratizing countries has more than tripled, according to the V-Dem Institute’s latest Democracy Report 2023.

International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy initiative has grown to assess the democratic status of 173 countries and its assessment work has been enhanced by the launch of a new Democracy Tracker, its Secretary-General Kevin Casas-Zamora writes in its latest report.

IDEA’s Global State of Democracy (GSoD) Report provides policymakers, activists, citizens and media with analysis, recommendations and data on democratic performance from 173 countries, while advocating for evidence-based democratic reforms, it adds. The report synthesizes 116 individual indicators from its GSoD Indices, including press freedom and clean and fair election processes.

IDEA’s Global State of Democracy (GSoD) Report provides policymakers, activists, citizens and media with analysis, recommendations and data on democratic performance from 173 countries, while advocating for evidence-based democratic reforms, it adds. The report synthesizes 116 individual indicators from its GSoD Indices, including press freedom and clean and fair election processes.

Given that democracy’s current challenges are rooted in the three major developments outlined above, observers will know therefore that the global democratic recession is receding when these developments change in the following ways, Carothers adds:

- A significant number of developing and postcommunist countries where attempted democratic transitions went off track manage to find new, more productive ways forward. Doing so will require a combination of a dauntingly long and challenging list of gains and reforms, including defeating elected autocrats, renovating prodemocratic political parties, widening the constituencies of independent civil groups, bolstering key guardrail institutions such as courts and electoral management bodies, strengthening the delivery of basic socioeconomic services, shoring up independent media, and nurturing local- and provincial-level oases of prodemocratic innovation.

Wealthy established democracies put illiberal parties and politicians on the defensive and reengage meaningfully with disaffected citizens by offering economic hope and results rather than stagnation and insecurity, achieving productive consensus over divisive social issues and forging solutions for making new technologies reinforce rather than disrupt societal cohesion.

Wealthy established democracies put illiberal parties and politicians on the defensive and reengage meaningfully with disaffected citizens by offering economic hope and results rather than stagnation and insecurity, achieving productive consensus over divisive social issues and forging solutions for making new technologies reinforce rather than disrupt societal cohesion.

- Major autocratic powers come up against hard limits to their efforts to undercut democracy beyond their borders and experience real competition to their attempts to serve as alternative models to liberal democracy.

The various recent pieces of good news on democracy touch all three of these categories, Carothers asserts. But much wider, sustained actions and progress in all three areas are necessary before it can be declared with confidence that the tide has turned for democracy globally. RTWT

Recent years have seen rising global concern about ‘democratic backsliding’, whereby political leaders challenge democratic norms and institutions and dismantle checks and balances on the executive, notes Professor Meg Russell, Director of the UK-based Constitution Unit. What can be done to combat these trends? In particular, how can international actors, and domestic actors such as opposition forces and civil society, work constructively to counteract or contain attempted backsliding?

In a recent seminar (below), an expert panel discuss what can be learnt from existing responses to backsliding. Speakers: Professor Kim Lane Scheppele, Laurance S. Rockefeller Professor of Sociology and International Affairs at Princeton University Ken Godfrey, Executive Director of the European Partnership for Democracy Dr Seema Shah, Head of Democracy Assessment at International IDEA.