In Latin America, as in other parts of the world with weak institutions, the coronavirus is threatening democracy. The United States should stand up for the rule of law in El Salvador, Bolivia, and Brazil, three countries where American policymakers retain influence, analyst Bo Carlson writes for The National Interest:

In El Salvador, President Nayib Bukele sent soldiers into the Legislative Assembly to threaten members of Congress. In Bolivia, interim President Jeanine Áñez has repeatedly delayed elections after a tumultuous transfer of power, citing coronavirus concerns. Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro mounted a police horse last month, leading a protest to intimidate the country’s Supreme Court. In each case, coronavirus has distracted international observers and provided an easy rationale for increasing executive power.

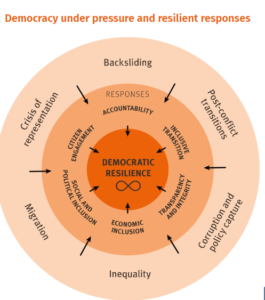

Democratic backsliding, a term describing the gradual rollback of institutions such as elections and legislatures, is not inevitable in Latin America, Carlson adds. In the most optimistic scenario, coronavirus may even bolster democracies, as people vote out incompetent populists.

Democratic backsliding, a term describing the gradual rollback of institutions such as elections and legislatures, is not inevitable in Latin America, Carlson adds. In the most optimistic scenario, coronavirus may even bolster democracies, as people vote out incompetent populists.

When does a global catastrophe stimulate a revival of international cooperation, rather than accelerate fragmentation and disorder? Council on Foreign Relations analyst Stewart M. Patrick asks. When does a crisis become a turning point in international relations, rather than just augur more of the same? These questions loom large in the COVID-19 pandemic, the biggest shock to world politics and the global economy since 1945. While history provides no definitive answers, it hints at three preconditions for resurrecting international cooperation from the ashes: new thinking, enlightened leadership and a favorable distribution of power, he writes for World Politics Review.

From democratic institutions finding ways to keep going online during lockdown to teams of fact checkers verifying the legitimacy of health claims made by governments and the media, COVID-19 has strengthened calls for democratic innovation globally, note analysts Khyati Modgil and Rosalyn Old. In the space of weeks, communities, businesses and authorities have expedited solutions that were previously resisted, highlighting their potential in helping citizens and authorities to navigate a changing world together, they write for the UK-based Nesta group:

International IDEA

Examples are emerging of governments, organisations and communities that have harnessed digital democracy tools in particular to ensure that citizen voices are heard in key choices around COVID-19 recovery. For example, the Scottish Government’s “Dialogue Challenge”, Demos’ People’s Commission, rapid online deliberation (by Involve, Ada Lovelace Institute, Traverse and Bang the Table), and online conversations (‘Challenges we face’ by Engage Britain).

While each project is unique, now more than before, they are facing similar challenges and see a need for change on similar themes, they add. This includes but is not limited to:

- Digital Tools: Whilst the uptake of digital tools and methods have supported more democratic means amongst institutions and organisations during COVID-19, organisations have cited concerns around exacerbating existing inequalities and the ongoing efficacy of taking everything online. Blended approaches, that factor in when and when not to make use of tools at scale will need to be tested going forward.

- Institutions and Governance: Are these fit for our current and future democracy? Where should power lie on which issues and what should be devolved further? What infrastructure is required to support greater local participation? Could different models of organising (e.g community ownership) be the answer – or do we need an impartial democracy institution to monitor and measure the health of our democracy?

- Supporting those furthest from power: Addressing inequalities in engagement and representation is a concern for all of our organisations who are keen to be more responsive to the needs of less represented groups. How can we embed the value of lived experience and the voices of minority groups in a way that is meaningful and relevant to those furthest from power?

- Civic Education & Information: While ideas and research are starting to emerge, very little is known about exactly how or why the current information landscape is affecting our civic and democratic actions. What is the role of civic education and ‘good’ information in holding power to account?

- The role of innovations across the spectrum of civic democratic engagement: Democracy is most effective and impactful when the ecosystem supports different types of initiatives that fill interconnected gaps and work together. In working with the Pioneers, many have called for a network of organisations trying to affect change in order to collaborate and test solutions more effectively.

Shalini Randeria, Director of the Graduate Institute’s Albert Hirschman Centre on Democracy, interviews Ivan Krastev, Permanent Fellow at the Institute of Human Sciences (IWM) Vienna and an associate of the NED’s International Forum (above).