Credit: RAND

The rule-based international order is under unprecedented strain because of both internal stresses on leading democracies and rising pressure from such challengers as Russia and China, the order — but it retains areas of persistent strength, argues RAND’s Michael J. Mazarr.

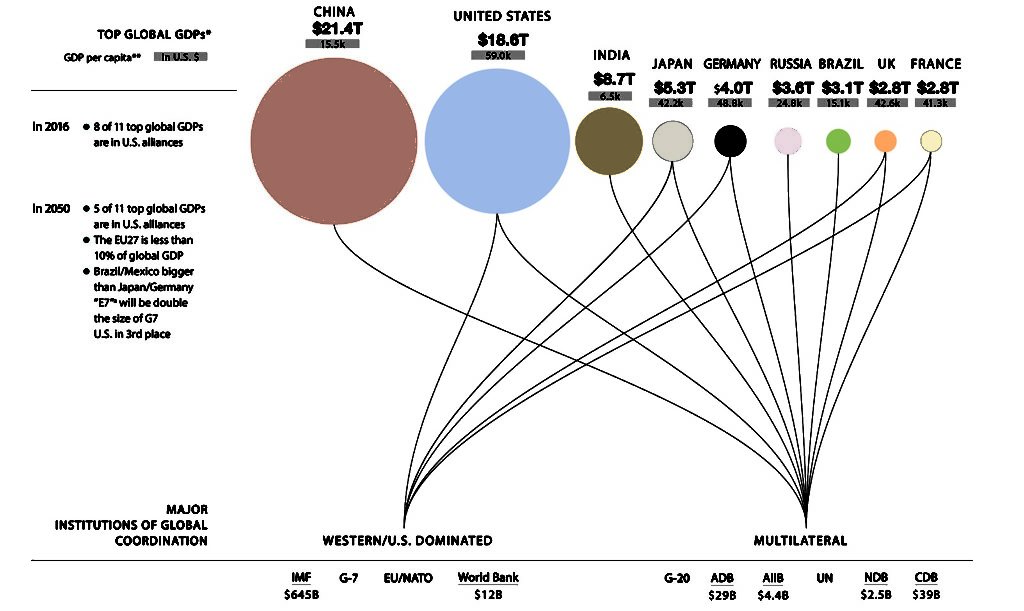

The question is whether the order retains strategic value, and whether such a vision can or should continue to shape U.S. strategy, he notes, adding that RAND’s major findings, summarized in a final overview report, include the fact that the postwar order has generated tremendous value for the United States and many other countries; that it retains impressive areas of resilience; and that challengers to the order, notably Russia and China, do not seek to destroy it so much as gain additional influence in its operation:

International orders tend to reflect the degree of community on the part of participating nations, especially the great powers of the era. One implication is that order is easiest to create and has its greatest effects among states that share significant norms and values—today, the global community of democracies. This finding also emphasizes the critical role of the guiding coalition at the heart of the order: If the coalition were to fragment, the order’s institutions, rules, and norms could not survive on their own.

International orders tend to reflect the degree of community on the part of participating nations, especially the great powers of the era. One implication is that order is easiest to create and has its greatest effects among states that share significant norms and values—today, the global community of democracies. This finding also emphasizes the critical role of the guiding coalition at the heart of the order: If the coalition were to fragment, the order’s institutions, rules, and norms could not survive on their own.

“Perhaps our most important conclusion emphasizes the value of the postwar order,” Mazarr adds. “It has boosted the effectiveness of other instruments of U.S. statecraft, we found, such as diplomacy and military strength, and helped to advance specific U.S. interests in identifiable and sometimes measurable ways.”

But we may be witnessing the “beginning of a fundamental break between America and the alliances and democratic values that have grounded U.S. foreign policy for decades,” according to a new report from the Center for American Progress.

But we may be witnessing the “beginning of a fundamental break between America and the alliances and democratic values that have grounded U.S. foreign policy for decades,” according to a new report from the Center for American Progress.

It would be a profound mistake to abandon democratic values, which have long been the moral compass of U.S. foreign policy….laws and norms that have made America a role model of democracy around the world, argue Kelly Magsamen, the CAP’s vice president for National Security and International Policy, and Michael Fuchs, a senior fellow at the Center.

Rapprochement with Russia risks playing right into Vladimir Putin’s strategy of weakening democratic Europe and inducing doubt in U.S. alliances, the report suggests.

Opinion survey results show that a strong majority of Americans realize promoting democracy is good for the United States—even if they do not think it is our most pressing foreign policy goal, notes Council on Foreign Relations analyst Elliott Abrams.

Opinion survey results show that a strong majority of Americans realize promoting democracy is good for the United States—even if they do not think it is our most pressing foreign policy goal, notes Council on Foreign Relations analyst Elliott Abrams.

“This means the key is leadership,” adds Abrams, a board member of the National Endowment for Democracy, the Washington-based democracy assistance group.. “The American public has not soured on promoting democracy or forgotten that the United States benefits when there are more democratic countries.”

“This means the key is leadership,” adds Abrams, a board member of the National Endowment for Democracy, the Washington-based democracy assistance group.. “The American public has not soured on promoting democracy or forgotten that the United States benefits when there are more democratic countries.”

The rise of populism means that liberalism and democracy are no longer naturally complementary, Yascha Mounk argues in The People versus Democracy: Why Our Freedom is in Danger and How to Save It, the FT adds, using survey data to chart the decline in support for democratic ideas in the west.