The Covid pandemic in Africa could well become a political emergency that threatens the democratic progress that countries across the continent have achieved in recent years, argue Alan Doss and Mo Ibrahim.

Africa is poorly placed to deal with the pandemic. Only a few countries have social safety-nets and the fiscal space to cushion the impact of the severe economic recession that both the IMF and World Bank have predicted. This convergence of economic, social and political crises is a recipe for unrest and instability, they write for The Economist:

Democratic elections might well be the spark that lights the fuse. More than 20 African countries were expected to hold national elections in 2020. Many of them were still in the midst of conflicts, just emerging from them, or on the verge. Only five of those—in Togo, Guinea, Mali, Burundi and Malawi—proceeded as scheduled, some peacefully, some with questionable outcomes. Fortunately, none seems to have provoked a covid-19 surge.

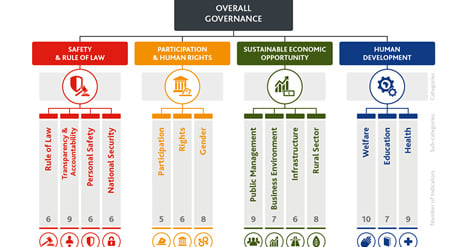

Governance progress slowed across Africa for the first time in a decade, even before the coronavirus pandemic hit, with commitment to democracy and civil rights faltering, the Mo Ibrahim Index of African Governance reported on Monday.

Governance progress slowed across Africa for the first time in a decade, even before the coronavirus pandemic hit, with commitment to democracy and civil rights faltering, the Mo Ibrahim Index of African Governance reported on Monday.

More than 60 percent of Africans live in countries that made progress in good governance over the period 2010 to 2019, this year’s report said. But progress has slowed in the last five years and this year, for the first time in the last 10 years, the combined score for all the countries fell year-on-year.

Since the pandemic began, some elections have been postponed while “the continent had been going through a deterioration of civil society space, participation and rights long before Covid-19,” said the report, which rates each country’s government according to criteria including anti-corruption measures, protection of civil liberties and caring for the environment.

There is “an increasingly precarious environment for human rights and civic participation” as well as a “deteriorating security situation,” it added.

Preliminary findings from Afrobarometer research (above) show that the majority of Africans still prefer the US over China as a development model, that China’s influence is still largely considered as positive for Africa, and that Africans who are aware of Chinese loans feel that their countries have borrowed too much, note Senior Research Associate at Oxford University, and Director of Research at the Centre for Democratic Development in Ghana.

Preliminary findings from Afrobarometer research (above) show that the majority of Africans still prefer the US over China as a development model, that China’s influence is still largely considered as positive for Africa, and that Africans who are aware of Chinese loans feel that their countries have borrowed too much, note Senior Research Associate at Oxford University, and Director of Research at the Centre for Democratic Development in Ghana.

This is important because – as both African and Chinese leaders reflect on their engagement – these findings should allow them to build a forward-looking relationship that better reflects African citizens’ opinions and needs, they write for The Conversation.

Less than a decade ago, much popular discourse touted the “Africa rising” narrative of a youthful, democratizing, tech-savvy continent destined for sustained economic growth, note Carolyn Logan, director of analysis for Afrobarometer (@afrobarometer) and associate professor in the Department of Political Science at Michigan State University, and E. Gyimah-Boadi, interim CEO of Afrobarometer.

Less than a decade ago, much popular discourse touted the “Africa rising” narrative of a youthful, democratizing, tech-savvy continent destined for sustained economic growth, note Carolyn Logan, director of analysis for Afrobarometer (@afrobarometer) and associate professor in the Department of Political Science at Michigan State University, and E. Gyimah-Boadi, interim CEO of Afrobarometer.

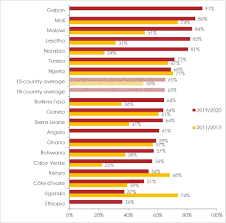

Yet in the recent surveys, about two-thirds (65 percent) said their country is going in the wrong direction, they write for The Post. Across 15 countries where Afrobarometer has asked these questions since 2011-2013, perceptions have deteriorated sharply over time: Average disapproval climbed from 50 percent to 65 percent (Figure 1 – right), including double-digit percentage-point increases in nine countries.

The World in 2021 – Alan Doss and Mo Ibrahim on protecting African democracy https://t.co/ZetEsJAOtT

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) November 17, 2020