In Samuel Huntington’s 1991 article on “Democracy’s Third Wave,” he argued that democratic declines are characterized by social and political polarization; the exclusion of populist and leftist movements by the middle and upper-class; terrorism; interventions by nondemocratic foreign powers; and a number of other conditions that bear a frightening resemblance to those of today’s world, notes analyst Clay Fuller. To make sure that a possible “fourth wave” of democratization is lasting, the work of democracy advocates must emphasize two new approaches, he writes for IRI’s Democracy Speaks:

- First, democracy advocates need to communicate the mission to wider audiences, especially those at home. And they must do so in a way that is transparent. Mission transparency means asserting and ensuring that democracy support is only about process and never about determining outcomes. However, in closed authoritarian states that reject the democratic process itself, democracy promotion is absolutely about supporting the rights of people (to be specific, registered voters) to put dictators out of business peacefully.

- Second, democracy promotion organizations must respond to endemic corruption and kleptocracy abroad. When there is no free press, no competitive elections and little regard for individual rights — such as property, speech, religion or assembly — corruption becomes ingrained in political and economic life. The result is kleptocracy, or rule by theft, which roots down like a weed and spreads across national borders.

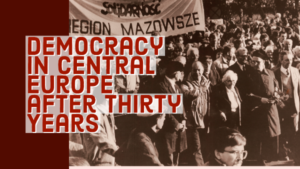

The 30 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989 have been marked by incredible progress toward a Europe “whole and free.” The European Communities became the European Union, grew to 28 member states, and helped raise living standards across the continent. NATO survived the end of the Cold War and expanded to 29 members. But today the challenges to that progress are many, the Brookings Institution writes:

The 30 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989 have been marked by incredible progress toward a Europe “whole and free.” The European Communities became the European Union, grew to 28 member states, and helped raise living standards across the continent. NATO survived the end of the Cold War and expanded to 29 members. But today the challenges to that progress are many, the Brookings Institution writes:

Far-right populists that reject the ideals of pluralism and liberal democracy upon which European integration rests have accumulated support across the continent. Russia’s annexation of Crimea and destabilization of eastern Ukraine mark the first time since World War II that a state has used force to change national borders in Europe. The alliance with the United States, which played a key role supporting European integration and security, has increasingly frayed while the United Kingdom is likely to leave the EU in the not-too-distant future, the first member state to ever do so.

The people of Central and Eastern Europe did not grow disillusioned with democracy, but rather with liberalism, Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes argue in their new book The Light that Failed. Voters rebelled against the “replacement of communist orthodoxy with a liberal orthodoxy.”

The people of Central and Eastern Europe did not grow disillusioned with democracy, but rather with liberalism, Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes argue in their new book The Light that Failed. Voters rebelled against the “replacement of communist orthodoxy with a liberal orthodoxy.”

Anglo-American thinkers such as Reinhold Niebuhr and John Gray have pointed out liberalism’s troubled relationship with democracy and human rights, and its overly complacent belief in reason and progress, argues Pankaj Mishra, author of “From the Ruins of Empire” and, most recently, “Age of Anger: A History of the Present.”

When Lionel Trilling claimed, in 1950, that liberalism in America was “not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition,” the term was becoming a catchall signifier of moral prestige, variously synonymous with “democracy,” “capitalism,” and even simply “the West.” Since 9/11, it has seemed more than ever to define the West against such illiberal enemies as Islamofascism and Chinese authoritarianism, he writes for the New Yorker:

The Economist proudly enlists itself in this combative Anglo-American tradition, having vigorously claimed to be advancing the liberal cause since its founding. In “Liberalism at Large” (Verso), Alexander Zevin, a historian at the City University of New York, takes it at its word, telling the story not only of the magazine itself but also of its impact on world affairs.

On Tuesday, November 12, the Center on the United States and Europe at Brookings will host a panel discussion to determine what the lessons of the past 30 years of European integration mean for the next 30 years. The discussion will be led by Brookings Robert Bosch Senior Visiting Fellow James Goldgeier, Nonresident Senior Fellow Victoria Nuland, Brookings Senior Fellow [and National Endowment for Democracy board member], and current Kissinger Chair at the Library of Congress Constanze Stelzenmüller, and Distinguished Fellow in Residence Strobe Talbott.

On Tuesday, November 12, the Center on the United States and Europe at Brookings will host a panel discussion to determine what the lessons of the past 30 years of European integration mean for the next 30 years. The discussion will be led by Brookings Robert Bosch Senior Visiting Fellow James Goldgeier, Nonresident Senior Fellow Victoria Nuland, Brookings Senior Fellow [and National Endowment for Democracy board member], and current Kissinger Chair at the Library of Congress Constanze Stelzenmüller, and Distinguished Fellow in Residence Strobe Talbott.

Europe 1989-2019: Lessons learned 30 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall

When: Tuesday, November 12, 2019, 2:00 – 3:30 p.m.

Where: The Brookings Institution, Falk Auditorium, 1775 Massachusetts Ave, NW, Washington, DC. RSVP

After the session, panelists will take audience questions. This event will be webcast live. Join the conversation on Twitter using #BBTI and #USEurope.