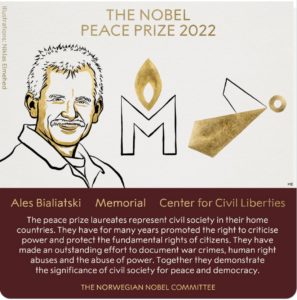

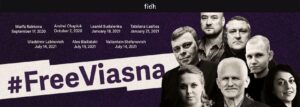

UN experts today reiterated calls for the release of Ales Bialiatski after the Nobel Committee’s decision to symbolically award him the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize for his fearless work promoting human rights in Belarus, according to reports.

Bialiatski founded the Belarus human rights group Viasna or “spring” in 1996. Bialiatsky was first jailed in 2011 and, in 2021, he was detained again without charge. Several of Bialiatsky’s Viasna colleagues also remain behind bars.

“There is a serious accountability gap for gross violations of human rights law in Belarus, and we welcome the solidarity of the international community and all efforts based on international law to persist in seeking justice,” the experts said.

Some Ukrainian activists and commentators have criticized the award to the jailed Belarusian human rights activist and Russian human rights group Memorial, alongside the Ukrainian Center for Civil Liberties for suggesting that there is some commonality between the three states.

Some Ukrainian activists and commentators have criticized the award to the jailed Belarusian human rights activist and Russian human rights group Memorial, alongside the Ukrainian Center for Civil Liberties for suggesting that there is some commonality between the three states.

But Volodymyr Yavorsky, a Ukrainian lawyer with the Ukrainian Center for Civil Liberties, told RFE/RL’s Current Time that he did not see the Nobel award as suggesting that “we are one people . . . and that the problem is that we need to be persuaded to live in peace,” Young adds:

The problem is that there are two authoritarian countries that are at war with a democratic country. . . . Today, this award emphasizes the fact that those people who are destroyed and persecuted in their countries—namely Belarusian and Russian human rights activists, who have been essentially forced to disband and some of whom are in prison—are basically fighting for freedom. And freedom is the antidote to this war and the antidote to the Russian regime.

Ales Bialiatski (far right) on a panel with NED’s Carl Gershman (far left) at Forum 2000.

It is wrong on both moral and practical grounds to conflate the citizens of an authoritarian state with the politics of the ruling clique, analyst Cathy Young writes for the Bulwark:

- On moral grounds, because the level of actual support for the war in Russia has been very difficult to gauge for many reasons, above all intimidation by the regime; in that sense, the blanket judgment that people fleeing mobilization were supportive of the Putin regime and complicit in its crimes against Ukrainians until they found themselves in personal danger is unwarranted and unjust. …

- On practical grounds, because the exodus of potential draftees does undermine Putin’s war: It means less manpower and more image problems…RTWT

Within broad movements for democracy and human freedom, certain individuals invariably emerge as transformational leaders, notes Carl Gershman, former president of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). They have the ability to articulate shared aspirations; their character is such that diverse factions gladly accept their leadership; their dedication is unquestioned; and their courage inspires others to make sacrifices for the common goal of building a more just society. Their goal is to serve a cause higher than themselves, and they do so not only to uplift the people they lead but to advance the universal principle of human dignity.

Credit: RFE/RL

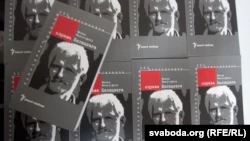

In the case of Belarus, often called Europe’s last dictatorship, the emblematic leader who stands in this tradition is a self-effacing human rights activist named Ales Bialiatski, he wrote back in 2014 in the introduction to The Byalyatski Matter (right), a book based on broadcasts about the renowned civil rights activist published by RFE/RL’s Belarus Service.

Belarus Service Director Alexander Lukashuk said that within the first month of publication the service has already received more than 1,500 requests for copies of the book from inside Belarus. Byalyatski, who received a copy of the book while in prison, was surprised and humbled.

“This book was a real Christmas gift for me,” he wrote from his prison cell. “I think it is something unprecedented, and, speaking sincerely, I didn’t feel too comfortable when I found myself in the center of its attention. But the book will have its own life.”

Bialiatski was active in the late 1980s, during the last years of the Soviet Union, as a dissident engaged in independent political and cultural activities, Gershman wrote nearly 10 years ago:

Bialiatski was active in the late 1980s, during the last years of the Soviet Union, as a dissident engaged in independent political and cultural activities, Gershman wrote nearly 10 years ago:

Since that time, his work has spanned the entire history of independent Belarus. He has been a “Renaissance activist” in terms of the many different ways he has served the cause of freedom: as a political dissident and cultural activist; as an academic, author and intellectual; as a political-party leader and an elected official in the Minsk city council; as an election monitor; and, above all, as an internationally respected human rights advocate. He was a founder of the first pro-democracy movement in Belarus – the Belarus Popular Front — as well as its first human rights organization – Belarus Witness. He has headed the Assembly of Belarusian Pro-Democracy NGOs, the country’s largest civil-society network. And in 1996 he founded — and since then has led — the Viasna Human Rights Center, the country’s foremost human rights organization, which has defended thousands of victims of political repression.

All of this work has been carried out at great personal sacrifice. Since 1988, Bialiatski has been arrested more than 20 times, most recently on August 4, 2011, after which he was sentenced to four-and-a-half years of maximum-security imprisonment on the charge of tax evasion with respect to the funds received by Viasna to aid the victims of repression. The charge was blatantly political, since Bialiatski’s real “crime” was defending human rights. But the Lukashenko regime would have been embarrassed to press such a charge, and so it concocted a legal formula to disguise its real motivation. But the strategy is too clever by half, and it has fooled no one. Bialiatski has been recognized as a political prisoner and a prisoner of conscience by the international community and human rights organizations, and he has been nominated for the third time for the Nobel Peace Prize.

All of this work has been carried out at great personal sacrifice. Since 1988, Bialiatski has been arrested more than 20 times, most recently on August 4, 2011, after which he was sentenced to four-and-a-half years of maximum-security imprisonment on the charge of tax evasion with respect to the funds received by Viasna to aid the victims of repression. The charge was blatantly political, since Bialiatski’s real “crime” was defending human rights. But the Lukashenko regime would have been embarrassed to press such a charge, and so it concocted a legal formula to disguise its real motivation. But the strategy is too clever by half, and it has fooled no one. Bialiatski has been recognized as a political prisoner and a prisoner of conscience by the international community and human rights organizations, and he has been nominated for the third time for the Nobel Peace Prize.

The Nobel Prize is an honor that Bialiatski richly deserves. Like Liu Xiaobo, the 2010 Nobel Laureate from China who was imprisoned when he received the prize and who remains behind prison walls, Bialiatski is an individual of great bravery and character. Prior to his arrest, he was aware of the case against him and had the opportunity to escape abroad, but he chose not to. He has always placed principle above politics, having left the political arena in the 1990s because of its divisive nature and because he felt he could make a greater contribution as a human rights advocate. In that role, he has helped everyone in need, regardless of party or ideology. He is one of the few opposition leaders who unites rather than divides. He is respected by everyone across the political spectrum of the opposition and could emerge from jail as a unifying political leader.

His political appeal is enhanced by his patriotism. Bialiatski is the archetypal Belarusian. He has always campaigned for the country’s independence and defended its language and culture, even as he has affirmed the European identify of Belarus and favors its integration into Europe as a free and democratic nation.

His political appeal is enhanced by his patriotism. Bialiatski is the archetypal Belarusian. He has always campaigned for the country’s independence and defended its language and culture, even as he has affirmed the European identify of Belarus and favors its integration into Europe as a free and democratic nation.

His appeal is also not unrelated to his modesty. Bialiatski has always been a low-key, quiet, committed activist who feels uncomfortable in the spotlight. He has no ego, doesn’t strive for recognition, and cares not a whit about the trappings of success. He’s modest in his speech, dress and behavior, and despite his academic background and intellectual achievement, he is very much an activist of the common man, most comfortable in jeans and on the streets, much like the late Polish activist Jacek Kuron. He has a wry wit, ever ready with a quip about the regime, the opposition, the European Union, even his own fate, as in the case of his comment that “During bad times, prison can be the best place for a human rights defender.” Most importantly, and despite his daunting work and the harsh circumstances of his existence, he is always smiling and is never without hope.

With his inspiring words and ironic tone now having been muted by imprisonment, his wife Natalia has become his public voice. She has put aside her historical studies and gardens in Rakau to raise his case – and the plight of the country’s other political prisoners – in Belarus and abroad. I was present just recently when she addressed the Wroclaw Global Forum and can testify to her eloquence and dignity.

Bialiatski can be compared to many famous freedom fighters – Vaclav Havel, Liu Xiaobo, and Jacek Kuron, among others. But there is a special affinity between him and a Burmese activist whom he may not even know about at all. I am thinking of Paw Oo Htun, whose nom de guerre Min Ko Naing means Conqueror of Kings. Like Bialiatski, Min Ko Naing was born in 1962, and he emerged in 1988 – just as Bialiatski was becoming active – as the most prominent leader of the student movement that rose up against the military dictatorship. He was arrested soon thereafter and spent most of the next two decades in prison, where he was often severely tortured. He is now out of prison as Burma’s very tentative political opening begins to unfold.

Bialiatski can be compared to many famous freedom fighters – Vaclav Havel, Liu Xiaobo, and Jacek Kuron, among others. But there is a special affinity between him and a Burmese activist whom he may not even know about at all. I am thinking of Paw Oo Htun, whose nom de guerre Min Ko Naing means Conqueror of Kings. Like Bialiatski, Min Ko Naing was born in 1962, and he emerged in 1988 – just as Bialiatski was becoming active – as the most prominent leader of the student movement that rose up against the military dictatorship. He was arrested soon thereafter and spent most of the next two decades in prison, where he was often severely tortured. He is now out of prison as Burma’s very tentative political opening begins to unfold.

On August 28, 1988, Min Ko Naing gave the opening address at the congress called to revive the All Burma Federation of Student Unions, which had been abolished in 1962 when the military seized power in Burma. His words addressed the challenge in Burma at the time, but they resonate today when we think of Bialiatski and Belarus. Min Ko Naing spoke of the long struggle to tear down the wall of dictatorship, which was “too thick” in the beginning but was beginning to show cracks. “If we unite,” he said, “and push down the wall, it will totally crumble and fall down.” He then closed with a poem that he wrote entitled “Faith,” which contained the following stanza:

Even if my life is sacrificed

for this unfulfilled revolution

I will not mourn for leaving this world.

instead I will be satisfied

that I was dedicated to our people.

Bialiatski shares that dedication, which is one of the reasons why it’s only a matter of time before the wall of dictatorship in Belarus will crumble and fall down. When that time comes, he will be remembered as a quiet hero whose courage helped his country become free. Until then, he deserves – and should receive – our full solidarity.