While democracy remains a popular aspiration around the world, “attraction” will prove more effective than “promotion” as a way to help democracy expand, says a leading analyst.

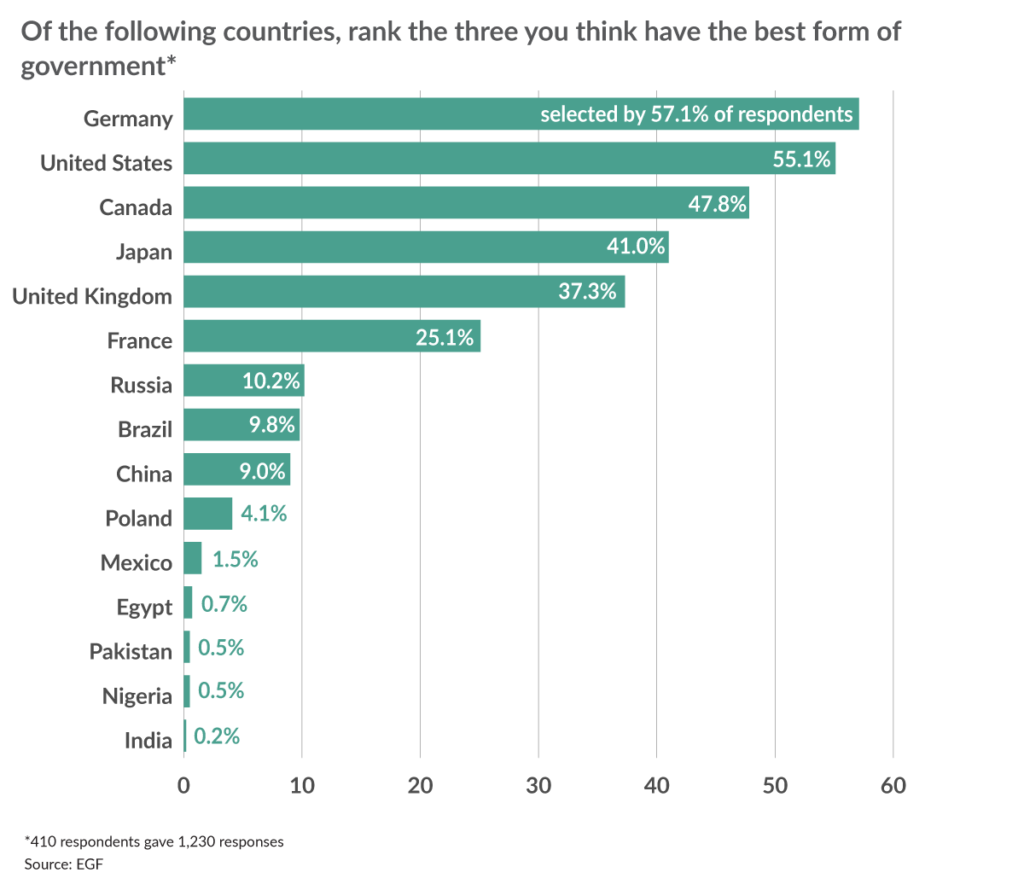

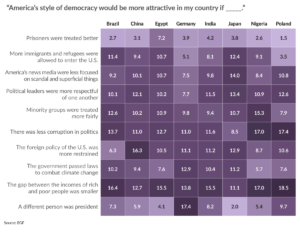

A new study conducted by the Eurasia Group Foundation (EGF) has produced interesting findings on public attitudes in other countries toward the U.S. and its system of government, notes EGF head Ian Bremmer. Based on surveys of citizens in eight countries—Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Nigeria, Poland, Germany and Japan—the report, authored by Mark Hannah, found support in all these countries for democracy but mixed attitudes toward the U.S. and its democracy, he writes for TIME.

Respondents in China were three times as likely to want their system of government to become more like the American system as less like it, he adds. Chinese sentiment toward the U.S. is largely positive, and this represents an opportunity for mutual appreciation, the authors observe:

Most of the Chinese public we surveyed believes America’s democracy and free market economy sets “a positive example for the world,” and so the suggestion by some that ideological conflict between the U.S. and China is inevitable and intractable seems undermined by these findings.”

There are at least four primary and interrelated reasons why democracy promotion efforts fail, the study contends:

There are at least four primary and interrelated reasons why democracy promotion efforts fail, the study contends:

• Emphasis on laws and institutions over political cultures which underpin them.

• Assumption that rights realized by democracy are universally prioritized over other desires.

• Military intervention as a self-defeating tactic of democracy promotion.

• Misunderstanding the values and interests of foreign publics we seek to champion.

The study cites research by Yascha Mounk and Stefano Foa in the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy claiming that one quarter of American millennials agreed that “choosing leaders through free elections is unimportant.”

The study cites research by Yascha Mounk and Stefano Foa in the National Endowment for Democracy’s Journal of Democracy claiming that one quarter of American millennials agreed that “choosing leaders through free elections is unimportant.”

Like a lot of public opinion research, the study generates more questions than answers, the authors concede, outlining some possible questions which could help guide policymaking and move us from a strategy of democracy promotion to one of democracy attraction:

- How might U.S. diplomats shift their pro-democracy rhetoric from an emphasis on shared values to one on diverse values in a way that humbly and implicitly acknowledges America’s version of democracy might not be the most preferable in every country at every moment?

- How can the U.S. double down on the goodwill and international influence currently generated by its soft power and integration of foreign-born diaspora communities? What kinds of visa programs might it expand or cultural exports might it further encourage?

- Instead of working with large, international institutions to put economic and political pressure on leaders of foreign governments to commit to democratic reforms, how might the U.S. better model a system of government which stokes the democratic aspirations of ordinary citizens.

- How might U.S. think tanks more critically engage with the assumptions of democracy promotion, and gain more awareness of their own cultural and epistemic biases?

- How might technological advances (e.g. expanding internet connectivity) create more channels for American cultural products to reach populations in countries with a democratic deficit?

- Can further research elaborate on the reputational benefits to democracy of cultural exchange, and the reputational damage brought about by foreign perceptions of U.S. political leaders, internationally unpopular military interventions, and impressions of economic disparity in the U.S.?

- How real and long-lasting can the global “democratic recession” be if public support for democracy and democratic ideas appears so resilient – especially in countries, such as China, with competing political models?