China’s President Xi Jinping and his comrades have been weathering a political storm, with the growing pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong adding to pressure on a regime already locked in a damaging trade war with the United States, The Washington Post reports.

“Xi Jinping and the rest of the Chinese leadership are under siege,” said Elizabeth Economy, a China expert at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“The Chinese economy is slowing significantly, exacerbated by the trade war; and the ‘China model’ is cracking under the weight of Xinjiang, Taiwan, Belt and Road messes and, most significantly, the massive protests in Hong Kong,” she said, referring to China’s efforts at control and influence within its borders and beyond. (Will China’s Next Crisis Be in Tibet? James Flynn asks in The American Interest).

“The Chinese economy is slowing significantly, exacerbated by the trade war; and the ‘China model’ is cracking under the weight of Xinjiang, Taiwan, Belt and Road messes and, most significantly, the massive protests in Hong Kong,” she said, referring to China’s efforts at control and influence within its borders and beyond. (Will China’s Next Crisis Be in Tibet? James Flynn asks in The American Interest).

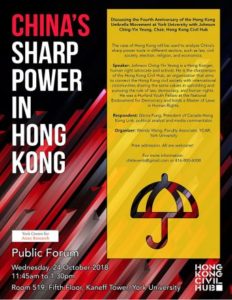

Beijing is conducting information warfare against Hong Kong’s democracy movement, reports suggest.

China has long curated the content that it allows its citizens to see and read. Its new campaign has echoes of tactics used by other countries, principally Russia, to inundate domestic and international audiences with bursts of information, propaganda and, in some cases, outright disinformation, according to The New York Times.

“Propagandists observe each other across borders, and they learn from each other,” said Peter Pomerantsev, the author of “This is Not Propaganda,” a new book that describes how authoritarian governments have weaponized social media that were once hailed as harbingers for democratic ideals.

“Propagandists observe each other across borders, and they learn from each other,” said Peter Pomerantsev, the author of “This is Not Propaganda,” a new book that describes how authoritarian governments have weaponized social media that were once hailed as harbingers for democratic ideals.

There is no sign of protests spilling over into the mainland, but these are concerns that Xi knows he needs to address, said Yu Jie, senior research fellow on China at Chatham House in London.

At the most recent Politburo meeting, Xi listed three domestic priorities: stabilizing employment, boosting household consumption and mitigating major risks, he told The Post.

“As the People’s Republic’s 70th birthday approaches, the world’s largest political party must tell a convincing story that its policies will work for everyone in China,” Yu said. “That story is not about a victorious conclusion for President Xi in dealing with external pressures but rather a story that continues to legitimize the party’s rule by providing jobs and domestic social stability.”

To inoculate itself, Beijing has turned to a raft of disinformation tactics to stir up nationalist support at home, creating a very different narrative of what is happening in Hong Kong by levying its control over the flow of information, NPR adds.

“The [protest] movement is so complicated, unpredictable and unprecedented, with a very diverse group of participants,” says Fang Kecheng, a communications professor at Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK).

“The [protest] movement is so complicated, unpredictable and unprecedented, with a very diverse group of participants,” says Fang Kecheng, a communications professor at Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK).

“But what we see within the Great Firewall of China is actually simplified and distorted,” he says. “That is because nationalistic content is politically safe and highly popular among the Chinese public and internet users.”

U.S. disengagement from Asia is worrying observers and diplomats, The New York Times reports.

“Without the steady centripetal force of American diplomacy, disorder in Asia is spinning in all sorts of dangerous directions,” said William J. Burns, a deputy secretary of state in the Obama administration and the president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “The net result is not only increased risk of regional turbulence, but also long-term corrosion of American influence.”

After more than four months of protests, the US administration has mainly called for both sides to avoid violence, while denying Beijing’s accusations of US interference, AFP adds.

“The only side the US should be on is democratic rights for the people of Hong Kong,” said Nicholas Burns, a former senior US diplomat now at the Harvard University Kennedy School.

Hudson

China’s leaders may well be sensing that the best – or even the only – way to restore their authority in Hong Kong is by force. But whether they do so now, or in two months – after the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic on Oct. 1 – a Tiananmen-style crackdown is not the answer, argues Minxin Pei, a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College, the author of China’s Crony Capitalism, and the inaugural Library of Congress Chair in U.S.-China Relations.

For starters, Hong Kong’s 31,000-strong police force lacks the manpower, and its officers may refuse to use deadly force; after all, there is a big difference between firing rubber bullets at a crowd and potentially murdering civilians, adds Pei, a contributor to the NED’s Journal of Democracy. This means that China would have to deploy the local PLA garrison or transfer tens of thousands of paramilitary soldiers (the People’s Armed Police) from the mainland, he writes for Project Syndicate:

Hong Kong’s residents would almost certainly treat Chinese government forces as invaders and mount the fiercest possible resistance. The resulting clashes would mark the official end of the “one country, two systems” arrangement, with China’s government forced to assert direct and full control over Hong Kong’s administration.

Hong Kong’s residents would almost certainly treat Chinese government forces as invaders and mount the fiercest possible resistance. The resulting clashes would mark the official end of the “one country, two systems” arrangement, with China’s government forced to assert direct and full control over Hong Kong’s administration.- With the Hong Kong government’s legitimacy destroyed, the city would become ungovernable. Civil servants would quit their jobs in droves, and the public would continue to resist. Hong Kong’s complex transit, communications and logistics systems would prove easy targets for defiant locals determined to cause major disruptions. And because the vast majority of Hong Kong’s residents are employed by private businesses, China cannot control them as easily as mainlanders who depend on the state for their livelihoods.

- The economic consequences of such an approach would be dire. Some Communist Party leaders may think that Hong Kong, which now accounts for only 3% of Chinese GDP, is economically expendable. But the city’s world-class legal and logistical services and sophisticated financial markets, which channel foreign capital into China, mean that its value vastly exceeds its output.

- If Chinese soldiers storm the city, an immediate exodus of expats and elites with foreign passports and green cards will follow, and Western businesses will relocate en masse to other Asian commercial hubs. Hong Kong’s economy – a critical bridge between China and the rest of the world – would almost instantly collapse.

When there are no good options, leaders must choose the least bad one, Pei contends.