The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered widespread concern about democracy, with pundits like Larry Diamond claiming that democracy is now under imminent threat as authoritarian tendencies take over. The ability of authoritarian governments to control their populations and prevent the spread of the disease may appear like an upside for dictatorial regimes, according to Adam Day, head of programmes at the United Nations University Centre for Policy Research, and Dirk Druet, a former official in the UN’s Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs and a visiting researcher at McGill University’s Centre for International Peace and Security Studies.

Twitter/UN

“However, in a new report, When Dictators Fall: Preventing Violent Conflict During Transitions from Authoritarian Rule, which we helped author, on how authoritarian regimes fall, we point to a troubling prospect: Many countries with strong authoritarian governments are more susceptible to economic shocks, much more likely to experience a collapse in regime when a strong downturn occurs and more at risk of descending into violent conflict than are more conventional democracies. This research suggests that governments (and financial markets) should be worried about a rise in violence as the pandemic takes hold in these economies, given that those very governments have often failed to deal effectively with systemic inequalities,” they write for The Hill.

Counterintuitively, this research has found that poor governance does not necessarily impact the risks of violence when an authoritarian regime falls. Countries with extremely poor governance ratings often experience quite peaceful transitions, while some of the most violent transitions have occurred in countries with relatively good governance scores. What matters more are two related factors: how a regime falls (by coup, uprising, election or death), and the levels of inequality within that country. Countries with extremely high levels of inequality are not only more likely to experience popular uprisings, they are also more likely to relapse into authoritarian rule after the transition.

Emergency measures to block transmission of the coronavirus have spread around the world along with the pathogen itself. By the end of May, at least 133 countries had imposed some sort of restriction on internal movement, for example, adds Amy Slipowitz, Research Manager for the Freedom House Freedom in the World survey.

Credit: Freedom House

However, restricting one right to address a genuine need can lead to violations of other rights. Among those suffering disproportionate effects from COVID-19 are women, prisoners, students, and racial or ethnic minorities such as black Americans. The ways in which public health restrictions have reverberated across society illustrate the interconnectedness and interdependence of all human rights and components of democracy, she contends.

“He’s losing support and needs something to put in its place,” said Maurício Santoro, a professor of political science at the State University of Rio de Janeiro. “Bolsonaro needs people on the street defending him.”

Even with a mantra of “We’re all in this together,” the COVID-19 crisis may stress-test a country’s social fabric. How “together” are African societies? Afrobarometer’s Brian Howard asks. In its 17th Pan-Africa Profile, it reports that Africans have a strong foundation of tolerance toward other ethnicities, religions, and nationalities on which to build. But tolerance toward people of different sexual identity or orientation remains remarkably weak, even among younger respondents. Minorities still experience discrimination based on ethnicity, religion, gender, or disability, and majorities in some countries report that the government treats their ethnic group unfairly.

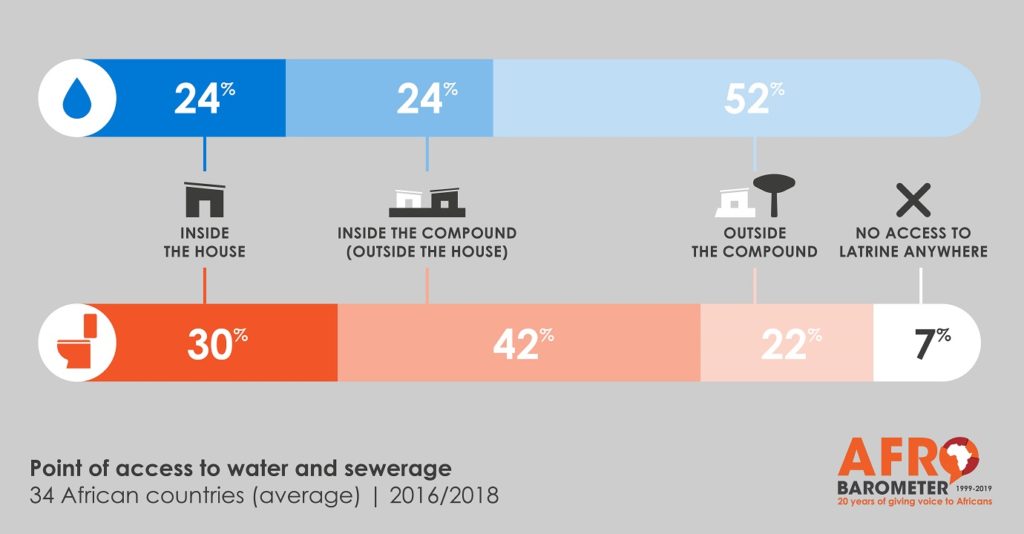

The findings from Afrobarometer’s Round 7 surveys (2016-2018) across 34 countries can be used to map pre-existing social and economic vulnerabilities, the World Bank reports. The data also confirm the prevalence of several factors in the domestic political environment that are likely to compound the challenges governments face in managing the COVID-19 crisis, including widespread, though not universal, lack of trust in elected leaders and official corruption. However, the findings also reveal the popular acceptance of the legitimacy of state law enforcement, as well as trust in informal leaders.

The findings from Afrobarometer’s Round 7 surveys (2016-2018) across 34 countries can be used to map pre-existing social and economic vulnerabilities, the World Bank reports. The data also confirm the prevalence of several factors in the domestic political environment that are likely to compound the challenges governments face in managing the COVID-19 crisis, including widespread, though not universal, lack of trust in elected leaders and official corruption. However, the findings also reveal the popular acceptance of the legitimacy of state law enforcement, as well as trust in informal leaders.

Interviewed by Sky News Australia’s Andrew Bolt (below), UN Watch’s Hillel Neuer says there is quite clearly a “culture of corruption” at the World Health Organization exemplified by senior Chinese officials named as “Goodwill Ambassadors.” Mr. Neuer pointed to Chinese state media journalist James Chau and Chinese President Xi Jinping’s wife, who were named WHO’s Goodwill Ambassadors by former Director-General Margaret Chan.

“James Chau is a British-born, University of Cambridge graduate who sold his soul to the Chinese communist party,” said Neuer. “For the wife of the Chinese dictator, Peng Liyuan, perhaps the argument could be made that the World Health Organization is co-opting her to spread the message of world health,” he said. However, Neuer told Sky News, it is more likely China has “succeeded in co-opting the World Health Organization.”

COVID-DEM has added a new resource to its Databases Hub. The Trinity Centre for Constitutional Governance at Trinity College Dublin (Ireland) has joined forces with the Corporate Law, Governance and Capital Markets research group to establish the COVID-19 Law and Human Rights Observatory. It also highlights the forthcoming webinars

COVID-DEM has added a new resource to its Databases Hub. The Trinity Centre for Constitutional Governance at Trinity College Dublin (Ireland) has joined forces with the Corporate Law, Governance and Capital Markets research group to establish the COVID-19 Law and Human Rights Observatory. It also highlights the forthcoming webinars

Today International IDEA: ‘Democracy in the times of Corona’ – 9 June 2020, 9:45-11:45 CEST

- Thursday International IDEA: ‘The Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis on Constitutionalism and the Rule of Law in East Africa’ – 11 June 2020, 2:00-4:45pm East Africa Time

- Friday Gilbert + Tobin Centre: ‘Public Law Responses to COVID-19 – COVID-19 and COVIDSafe’ – 12 June 2020, 1:00-2:00 pm (AEST)

Professor Emmanuel Gyimah Boadi (above), co-founder and interim CEO of Afrobarometer, will discuss how these strengths can be harnessed for the effective management of the pandemic. He is also co-founder and former executive director of the Ghana Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana, a leading independent democracy and good governance think tank). A former professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Ghana, Legon, he has held faculty positions at universities in the United States, including the American University School of International Service, and fellowships at the Center for Democracy, Rule of Law and Development (Stanford University); the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars; and the International Forum for Democratic Studies/National Endowment for Democracy.

- PLACE: Online

- DATE: Tuesday June 9, 2020

- TIME: 12:30 – 2:00 PM (ET)

It is evident that Coronavirus has transformed our world. But what will its impact be on international relations and global politics? The Henry Jackson Society asks.

It is evident that Coronavirus has transformed our world. But what will its impact be on international relations and global politics? The Henry Jackson Society asks.

Whether it is changes in the international order and how that order interacts, the future of globalisation, China’s global role, the relative strengths of the free versus unfree world or possibilities of political upheaval, many questions have been thrown up by the pandemic, but few answers thus far have emerged.

The Society hosts Professor Niall Ferguson – the author of 15 best-selling books and a renowned authority on global transformations – to share his thoughts on the changes to world affairs as we have known them that we can expect going forwards. Professor Ferguson will be in conversation with Dr Alan Mendoza, Executive Director of the Henry Jackson Society, following which Q&A will be conducted with the audience. 15:00-16:00 (BST) Friday 12th June 2020. RSVP. Please register via ZOOM.

“The far-right

“The far-right