Poland and Hungary have used the largesse of the European Union to undermine democracy and the rule of law, according to a new Bloomberg analysis:

Hundreds of billions of euros of EU cash has gone toward everything from new hospitals and schools to highways and high-speed rail links, funds that are given to poorer regions to catch up with richer ones, note analysts Wojciech Moskwa, Zoltan Simon, and Rodney Jefferson. It’s also been channeled into social programs and enabled “great possibilities of patronage” as leaders used funds and contracts to reward political allies, says Timothy Garton Ash, professor of European Studies at Oxford University.

“The EU has done more to sustain these governments than it has to constrain them,” he told Bloomberg. “There’s a growing understanding in the EU that something has gone wrong here and that the erosion of democracy and the rule of law in Hungary and in Poland is a threat to the entire legal order and indeed the democracy and legitimacy of the EU.”

“The EU has done more to sustain these governments than it has to constrain them,” he told Bloomberg. “There’s a growing understanding in the EU that something has gone wrong here and that the erosion of democracy and the rule of law in Hungary and in Poland is a threat to the entire legal order and indeed the democracy and legitimacy of the EU.”

The EU has plowed almost €200 billion into Poland alone since it joined the bloc and another €68 billion into Hungary, which is a quarter of Poland’s size, Bloomberg adds:

The EU has strict procurement rules when it comes to disbursing the money, though member states are relied upon to police them. In recent years, how the money was spent has become more political. ….There are myriad ways in which EU funding distorts the economic and political system, according to Istvan Janos Toth, director at the Corruption Research Center in Budapest, who has analyzed hundreds of thousands of public procurement contracts. Pro-government municipalities, for example, are much more likely to get EU funding.

“Loyalty to the government is the most important factor in the distribution of EU funds,” says Jozsef Peter Martin, director of Transparency International in Hungary. “For a long time the EU didn’t do anything, it turned a blind eye. It’s unclear if it’s too late by now.”

Democracy is at risk in the Balkan countries seeking to join the European Union, with Bosnia a particular concern, Croatia’s foreign minister warned on Monday as the EU’s top diplomat promised to revive North Macedonia’s membership bid, Reuters reports.

Poland and the European Union are also gripped in an ongoing, tense feud over the issue of rule-of-law reform. Since coming to power in 2015, the Law and Justice Party (PiS) has put forward a series of controversial measures overhauling the Polish judiciary, notes Hugo Blewett-Mundy, a researcher at UCL’s School of Slavonic and East European Studies and a writer for Lossi 36.

Poland and the European Union are also gripped in an ongoing, tense feud over the issue of rule-of-law reform. Since coming to power in 2015, the Law and Justice Party (PiS) has put forward a series of controversial measures overhauling the Polish judiciary, notes Hugo Blewett-Mundy, a researcher at UCL’s School of Slavonic and East European Studies and a writer for Lossi 36.

PiS insist that their reforms are needed to fix a system plagued with inefficiency born out of the communist period. The EU says the proposed changes threaten fundamental European values in democracy and the rule of law. To understand why Law and Justice believes its reforms are required, it is useful to look back at the collapse of communism in 1989. Did Poland consolidate liberal democracy after 1989? he asks in the EU Observer.

Oleh Havrylyshyn’s superb book, Present at the Transition makes an invaluable contribution to transition literature, particularly in assessing which transition strategies have generated the best outcomes, adds analyst Martin Miszerak. Using ample data, he proves beyond any shadow of doubt that those countries, such as Poland and Hungary, that pursued “big bang” reforms, sometimes pejoratively referred to as “shock therapy,” generated the best results, defined as fast economic growth and relative income equality.

Oleh Havrylyshyn’s superb book, Present at the Transition makes an invaluable contribution to transition literature, particularly in assessing which transition strategies have generated the best outcomes, adds analyst Martin Miszerak. Using ample data, he proves beyond any shadow of doubt that those countries, such as Poland and Hungary, that pursued “big bang” reforms, sometimes pejoratively referred to as “shock therapy,” generated the best results, defined as fast economic growth and relative income equality.

Hysteresis

The rise of right-wing populism in Hungary and Poland is primarily the result of hysteresis, he writes for Global Policy. These countries have simply not been able to overcome the burden of history, even though the post-1989 reformers made a valid attempt to do so. While Hungary and Poland are obviously “European” in a geographic sense, the key question is whether they are “European” in a cultural and philosophical sense, and whether it was at all reasonable to expect them to become liberal democracies.

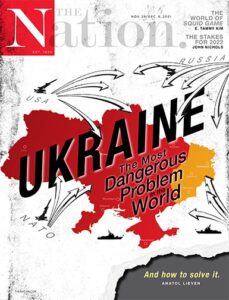

Given the slim and distant prospects of Ukraine qualifying for EU or NATO membership, Ukrainian politicians might wish to study the examples of Finland, Sweden, and Austria during the Cold War, argues Anatal Lieven. These states lost nothing through neutrality and developed as prosperous, law-abiding, democratic Western societies that were able to join the EU after the Cold War ended. They could achieve this not through an EU or NATO accession process but rather because the elites and populations of these countries were genuinely committed to democracy, the rule of law, and regulated market economics, he writes for The Nation.

Given the slim and distant prospects of Ukraine qualifying for EU or NATO membership, Ukrainian politicians might wish to study the examples of Finland, Sweden, and Austria during the Cold War, argues Anatal Lieven. These states lost nothing through neutrality and developed as prosperous, law-abiding, democratic Western societies that were able to join the EU after the Cold War ended. They could achieve this not through an EU or NATO accession process but rather because the elites and populations of these countries were genuinely committed to democracy, the rule of law, and regulated market economics, he writes for The Nation.

The common goal of certain commentators – including Ryszard Legutko, author of The Demon in Democracy: Totalitarian Temptations in Free Societies, and Patrick Deneen, author of Why Liberalism Failed, is to conflate liberal democracy with contemporary progressivism and thus to suggest that conservatives should have no interest in supporting or defending liberal democracy, notes Marc F. Plattner, a board member of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

Many other conservatives, of course, including most of the still dominant center-right parties in Europe, remain committed to liberal democracy. But today’s intellectual and political currents do not appear to be trending their way, he writes for the NED’s Journal of Democracy.

Many other conservatives, of course, including most of the still dominant center-right parties in Europe, remain committed to liberal democracy. But today’s intellectual and political currents do not appear to be trending their way, he writes for the NED’s Journal of Democracy.

The illiberal right in both Poland and Hungary came to power harnessing material anxieties related to the growing crisis of social reproduction—the declining ability of societies to create and maintain social bonds and provide care between and within generations, adds Weronika Grzebalska, an assistant professor at the Institute of Political Studies of the Polish Academy of Sciences and a RethinkCEE fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the US. By promising to protect ‘family values’ amid the progressive decline of socio-economic security, and by offering families vital endowments, central-European illiberals have rallied even moderate voters behind their agenda, she writes for Social Europe.

What motivates some people to struggle for democracy? Vaclav Havel asked of Czechs and Slovaks. “Where did (our) young people … (find) their desire for truth, their love of free thought, their political ideas, their civic courage?” The answer lies in the human desire to choose the types of societies we want to build for ourselves — ones grounded on values of dignity for all and the rule of law, noted former Canadian MP David Kilgour. The citizens of the Czech Republic in a national election recently removed the last Communists from their parliament after 100 years of presence by giving the party less than four per cent of their votes, he told the 10th Anniversary Conference of the Platform of European Memory and Conscience.

While now problematic, both Hungary and Poland transitioned to democracy and a market economy after 1990, despite significant losses in markets for exports and in subsidies from the former Soviet Union. In short, the region’s transitions were difficult, but in virtually all East and Central European countries, life appears to be significantly better now than in 1989, Gilmour observed.

The European Union institutions need to ensure compliance with the Rule of Law to protect and foster democracy in the European Union, the European Movement International adds. At the same time, civil society organizations play a fundamental role in the protection of the Rule of Law principles and their work must be safeguarded and supported in shaping Europe’s future.

On Wednesday, 17 November 2021 from 12:15-13:30 CET, EMI will hold a digital panel discussion entitled Threats and Challenges to the Rule of Law (above). Civil society and leading political figures will share their views on the state of the Rule of Law in Europe and how they can foster citizen engagement and change:

On Wednesday, 17 November 2021 from 12:15-13:30 CET, EMI will hold a digital panel discussion entitled Threats and Challenges to the Rule of Law (above). Civil society and leading political figures will share their views on the state of the Rule of Law in Europe and how they can foster citizen engagement and change:

- Brando Benifei MEP (S&D), Vice President of the European Movement International

- Daniel Freund MEP (Group of the Greens/EFA)

- Vladimir Međak, Vice-President, European Movement Serbia

- Marcin Święcicki, President, European Movement Poland

- Beatrix Benczur, President, European Values Association, Hungary

Moderated by Petros Fassoulas, EMI Secretary General. Register HERE.

On Tuesday, 23 November 2021 from 14:00-15:30 CET, EMI host a Democracy Table discussion with Polish stakeholders to present the public opinion poll results from Listen to Europe: Reaching Beyond our Base Audience (LTE). RTWT