MERICS

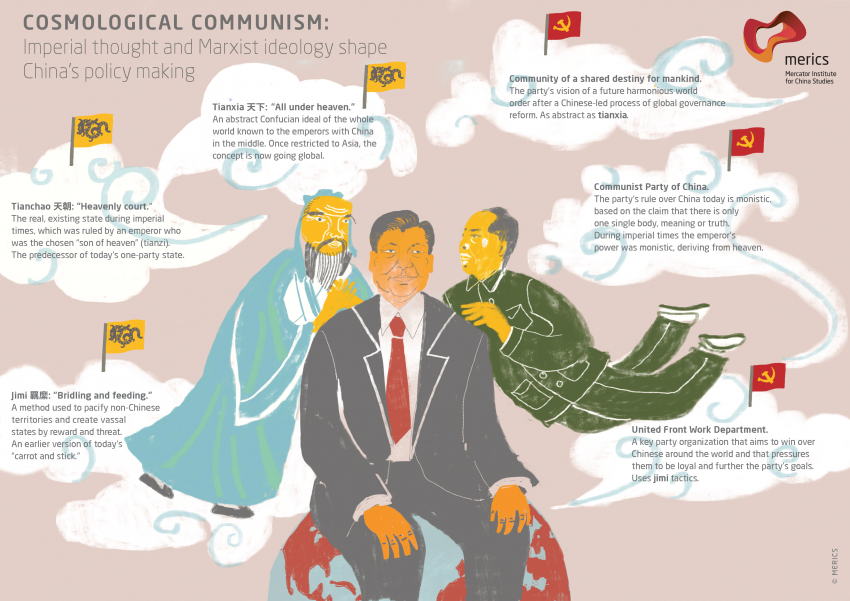

China’s ruling Communist Party rejects universalism as a Western concept but is substituting its own counter-universal values based on empire and party that Westerners have trouble understanding, argues analyst Didi Kirsten Tatlow. Older, enduring norms of power and statecraft {are} being ingested and reproduced by the CCP to project power and build legitimacy, she writes for MERICS’ China Monitor Perspectives:

The result: A hybrid, yet monistic, set of power and truth claims that encompasses both modern and pre-modern thought (monism being a worldview that ascribes to all varied phenomenon one truth). This unique set of norms is rooted in a cosmological worldview located in “the center,” where, under the emperors, and today under the party, final authority resides.

The result: A hybrid, yet monistic, set of power and truth claims that encompasses both modern and pre-modern thought (monism being a worldview that ascribes to all varied phenomenon one truth). This unique set of norms is rooted in a cosmological worldview located in “the center,” where, under the emperors, and today under the party, final authority resides.

Australia is standing up to China. Watch closely: It may be a harbinger of things to come, as the world’s smaller countries respond to the increasingly coercive Asian economic superpower, notes Reuters’ correspondent Kirstie Needham.

Australia has also voiced concerns in recent weeks about what it sees as Chinese disinformation campaigns that seek to undermine democracies; suspended its extradition treaty with Hong Kong over China’s imposition of a draconian security law in the city; and filed a declaration with the United Nations rejecting China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea, she writes in a must-read Special Report.

Australia has been collaborating with other democracies in the region, not least through the Quad alliance.

Australia has been collaborating with other democracies in the region, not least through the Quad alliance.

“Working with other middle powers, in our own region and globally, makes a lot of sense for Australia in the current environment. It helps show China we are not alone in our concerns,” said Richard Maude, a senior fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute, who led the government’s 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper. “It is also a helpful rebuttal of China’s narrative that Australia simply does what the United States asks of us.”

Free societies need to be able to meet twenty-first-century demands for citizen security and opportunity in order to compete effectively with rising authoritarian states, argues Robert B. Zoellick.

His recommendations for a new domestic-foreign policy combine novelty with continuity. During difficult days in the Cold War, Presidents Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush recognized the need to draw allies closer together. They prioritized building and strengthening partnerships before negotiating with their Soviet adversary, he writes for Foreign Affairs:

The same must be true today. This plan leads with topics of common interest among allies in Europe and the Pacific. Free societies need to be able to meet twenty-first-century demands for citizen security and opportunity. Acting in concert, the United States and its partners can become more attractive to others and compete effectively with rising authoritarian states. At the same time, this agenda, if promoted by a coalition, could offer common ground with China and Russia.

The same must be true today. This plan leads with topics of common interest among allies in Europe and the Pacific. Free societies need to be able to meet twenty-first-century demands for citizen security and opportunity. Acting in concert, the United States and its partners can become more attractive to others and compete effectively with rising authoritarian states. At the same time, this agenda, if promoted by a coalition, could offer common ground with China and Russia.

The relationship between EU member states and China is undergoing a transformation that the coronavirus crisis has accelerated, adds analyst Janka Oertel. While efforts to enhance trade and other economic links continue to play a major role in the relationship – especially due to the financial impact of the pandemic – countries across Europe are becoming increasingly sceptical of Beijing’s intentions, she writes for the European Council on Foreign Relations:

In contrast to authoritarian regimes, democracies find it very difficult to counter the weaponisation of social media. Although countering disinformation is a priority for the current European Commission and the subject has risen to the top of the agenda in many EU member states, the importance of strategic communication is not necessarily reflected in their institutional structures.

Beijing adopts an a la carte approach to international norms and institutions, analysts suggest.

China has rejected or violated the shared ideas of some of the international institutions it has joined. But as Columbia University professor Andrew Nathan – co-author of China’s Search for Security – points out, it has also partially or wholly complied with many other shared ideas, particularly because in many cases it has served its interests to do so.

China has rejected or violated the shared ideas of some of the international institutions it has joined. But as Columbia University professor Andrew Nathan – co-author of China’s Search for Security – points out, it has also partially or wholly complied with many other shared ideas, particularly because in many cases it has served its interests to do so.

Foreign policy analysts’ preoccupation with realism v. idealism, offshore balancing, primacy, hegemony, and similar theoretical considerations are not especially helpful, Zoellick writes in his new book, America in the World: A History of U.S. Diplomacy and Foreign Policy.

“The concepts from international relations and doctrines help frame debates, but they do not offer policy makers guidance about what to do.” Practitioners “considered strategic reference points – about geography, economics, power and politics – but prized flexibility, adaptability and trying what might work.”

Competition, and even rivalries, can be tempered by mutual interests, adds Zoellick, a former National Endowment for Democracy (NED) board member.

Required reading via @dktatlow for all serious analysts of China & great power competition. Highly recommended. @FrencLindley @GrayConnolly @FredKempe @wess_mitchell @SlawomirDebski @BartosiakJacek @CER_IanBond @lauremandeville https://t.co/vcf78ZprGh

— Andrew A. Michta (@andrewmichta) September 8, 2020