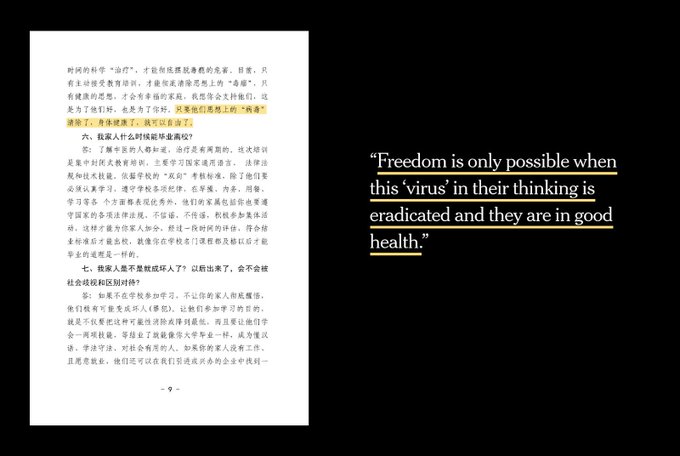

The New York Times @nytimes Publicly, Chinese officials say the Xinjiang camps provide job training. But privately, the documents show, they used words like “virus,” “infected” and “eradicate” to justify mass detentions and plotted how they would manage and intimidate families that were torn apart.

Beijing’s top political office in Hong Kong has called protesters a “political virus” and said the semi-autonomous city will never be calm until “poisonous” and “violent” black-clad demonstrators are eliminated, the Guardian reports:

The warning on Wednesday by China’s Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office (HKMAO) said the central government in Beijing would not sit idly by with “this recklessly demented force” in place, referring to the protest movement which has shaken Hong Kong since last June and sometimes drawn millions to the street.

It said the protesters and their oft-used mantra of “if we burn, you burn with us” were a “political virus”, and that the movement’s organisers wanted to “drag Hong Kong off a cliff”.

The rhetoric is the latest in a series of recent developments which have aroused suspicions of restrictions being used as political cover, allowing officials to take inflammatory actions without immediately rekindling last year’s anti-extradition, pro-democracy mass protests, adds China Digital Times, a National Endowment for Democracy (NED) partner.

The rhetoric is the latest in a series of recent developments which have aroused suspicions of restrictions being used as political cover, allowing officials to take inflammatory actions without immediately rekindling last year’s anti-extradition, pro-democracy mass protests, adds China Digital Times, a National Endowment for Democracy (NED) partner.

A pro-Beijing group of former officials, business tycoons, and university presidents launched a coalition (SCMP: HT – CFR) that aims to address the coronavirus, revive Hong Kong’s economy, and resolve a political crisis over the city’s anti-government protest movement.

The leaders of the Chinese Communist Party—and local Hong Kong authorities who take their cues from Beijing— have moved against the democracy movement in full awareness that they did so at much lower risk of setting off a major international backlash or large crowd actions than they would have faced just a few months ago, notes Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Chancellor’s Professor of History at the University of California, Irvine, and the author of Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink.

The leaders of the Chinese Communist Party—and local Hong Kong authorities who take their cues from Beijing— have moved against the democracy movement in full awareness that they did so at much lower risk of setting off a major international backlash or large crowd actions than they would have faced just a few months ago, notes Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Chancellor’s Professor of History at the University of California, Irvine, and the author of Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink.

Hong Kongers and on the so-called “international frontline” must know their strengths and bargaining chips on this negotiating table with Beijing, argues Dr. Simon Shen, the Founding Chairman of GLOs (Glocal Learning Offices), and an adjunct associate professor in the University of Hong Kong:

- Unlike Xinjiang and Tibet, Hong Kong is a city with transparency and free flow of information. Hong Kongers need to make a case to the world that the protests are not acts of terrorism. Some suggestions include comparing the Hong Kong protests to similar struggles in 20 or so other counties in the world at the present time, none of which were classified as terrorism; collecting a large amount of concrete evidence of the disproportionate use of force by the Hong Kong police; and showing how enacting Chinese national laws in Hong Kong will end the city’s autonomy and spell disaster for international community‘s interests.

- The Legislative Council is the institution that can counteract Beijing’s “boiling frog” strategy and to keep Hong Kongers’ hope alive in the system. Those who plan to run for legislative office must be prepared to be disqualified from running. If only individuals are banned, there need to be alternative candidates as back-up plans. However, if and when the disqualification process is applied broadly to entire camps of candidates (for example, all who object to Article 23), the pro-democracy camp must make a strong case to the Hong Kong and global public that this is the endgame for Hong Kong democracy…..

These recommendations delineates how the slogan “if we burn, you burn with us,” often seen in the protests, may play out in the game of international relations, Shen writes for the Diplomat:

These recommendations delineates how the slogan “if we burn, you burn with us,” often seen in the protests, may play out in the game of international relations, Shen writes for the Diplomat:

If the national security laws are “passed” by a legislature that is jury-rigged in this manner, or if related national laws are directly implemented in Hong Kong, Hong Kongers should signal clearly to the world that it goes way beyond the promised “one country, two systems.” Crossing this red line by Beijing should be seen by the world as a blunt violation of its promised autonomy to Hong Kongers. At that time, if the international community led by the United States and the United Kingdom decided to revoke the “non-sovereignty entity” status of Hong Kong and regard the SAR as an ordinary Chinese city, it shouldn’t come as a surprise.

Britain’s Lord David Alton has called on the UK to impose sanctions on Hong Kong officials for human rights violations (HT: Human Rights in China), the Hong Kong Free Press reports. HRIC also highlights an interview with Fu Hualing, Johannes Chan: In response to national security, what kind of Hong Kong do we want?)

Social media users associated with the Hong Kong protests described the virus rhetoric as intimidating language, and joined observers noting its similarity to Communist Party (CCP) discourse about Xinjiang and the detention of Uighurs, the Guardian adds.

Social media users associated with the Hong Kong protests described the virus rhetoric as intimidating language, and joined observers noting its similarity to Communist Party (CCP) discourse about Xinjiang and the detention of Uighurs, the Guardian adds.

Publicly, Chinese officials say the Xinjiang camps provide job training. But privately, the documents show, they used words like “virus,” “infected” and “eradicate” to justify mass detentions and plotted how they would manage and intimidate families that were torn apart, The New York Times @nytimes tweeted (above).