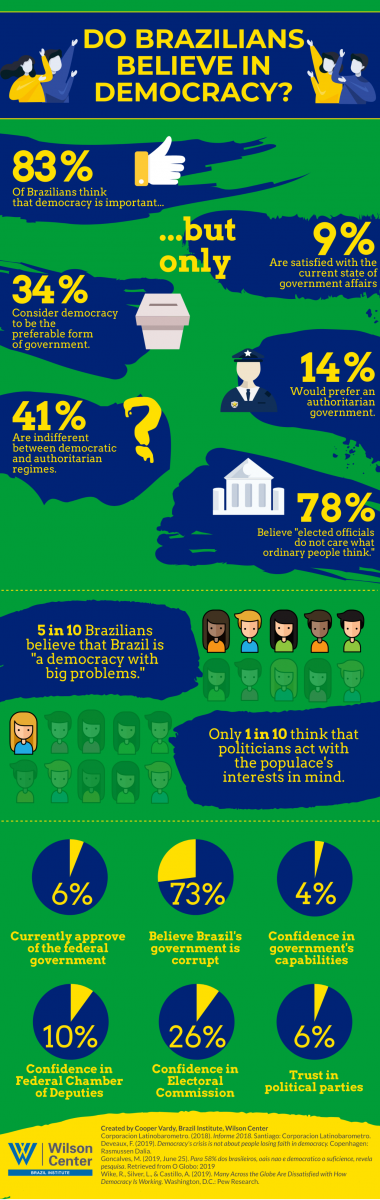

Credit: Wilson Center

Brazil’s democratic decline is rooted in domestic trends that predate Jair Bolsonaro’s rise to power, chief among them the incomplete assertion of civilian control over military leaders, notes Oliver Stuenkel, Associate Professor of International Relations at Fundação Getulio Vargas in São Paulo, Brazil. More than 6,000 military personnel currently serve in Bolsonaro’s administration—a sharp increase from previous governments—and current and former military officials hold many key cabinet positions.

Gradually worsening economic conditions—exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic—have only hastened the country’s democratic decay, he writes for Foreign Affairs:

Gradually worsening economic conditions—exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic—have only hastened the country’s democratic decay, he writes for Foreign Affairs:

Successive democratic governments have failed to provide basic public goods to many Brazilians, including security, proper sewage disposal, and access to economic opportunity. Even during Brazil’s boom years in the first decade of the millennium, when the economy grew at up to seven percent, homicide rates steadily rose. Today, about 50,000 Brazilians are murdered per year, and organized crime groups and militias control swaths of major cities such as Rio de Janeiro.

In diversity, democracy, even science, the Bolsonaristas see only enemies, and enemies to eradicate, analyst Julia Blunck writes for the London-based Prospect. The Bolsonaro movement taps into smoldering national anxieties—not least around race, in a society where the legacy of slavery and colonization has been a taboo subject until very recently—and combines this with generic 21st-century forms of disinformation: QAnon-style internet horrors and flat-earther dominated group chats.

In looking towards next year’s election, the question most Brazilians ask is not whether Bolsonaro will try for a coup, but how, Blunck adds.

Civil society groups like SITAWI, a National Endowment for Democracy (NED) partner, aim to promote democratic culture and the value of dialogue, tolerance, and citizen engagement as part of a process to defend democratic processes and principles. It is engaged with the Pacto Pela Democracia (Pact for Democracy) initiative, a civil society platform comprising a diverse group of actors, which is developing a democratic process monitoring mechanism.

Civil society groups like SITAWI, a National Endowment for Democracy (NED) partner, aim to promote democratic culture and the value of dialogue, tolerance, and citizen engagement as part of a process to defend democratic processes and principles. It is engaged with the Pacto Pela Democracia (Pact for Democracy) initiative, a civil society platform comprising a diverse group of actors, which is developing a democratic process monitoring mechanism.

Simultaneously, both the Biden administration and the European Union must make it very clear that any further attempts to undermine Brazil’s democratic institutions would have serious consequences for Bolsonaro, adds Stuenkel. If the president fails to change course, U.S. and European options should include downgrading military ties, halting ratification of the Mercosur-EU trade deal, and freezing Brazil’s admissions process to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. RTWT