Credit: ASPI

An overseas Chinese student in the US has been charged with stalking and threatening another Chinese student who took part in pro-democracy activism on their campus, the BBC reports:

US prosecutors say Xiaolei Wu, 25, sent threats to the girl and also reported her family to authorities in China. The Berklee College of Music student was arrested in Boston on Wednesday. He is alleged to have targeted the girl after she put up fliers calling for greater political freedom in China.

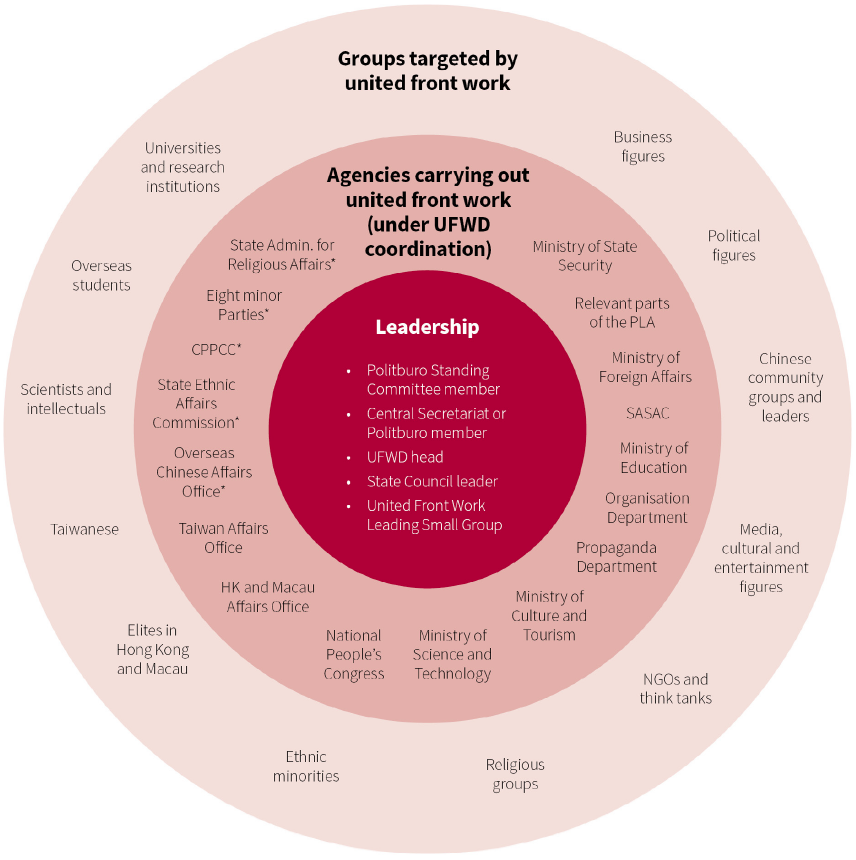

The incident will likely exacerbate concerns over China’s apparently ubiquitous threats to democracy, including campus-based Confucius Institutes, an element of the CCP’s United Front strategy (above), as documented by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

South Korea’s story is one in which political authoritarianism was accompanied by miraculously fast economic growth, which in turn became the material basis for a democratic push led by the middle class. Could China take a similar path? asks Keun Lee, Distinguished Professor of Economics at Seoul National University and the author of China’s Technological Leapfrogging and Economic Catch-up: A Schumpeterian Perspective.

South Korea’s story is one in which political authoritarianism was accompanied by miraculously fast economic growth, which in turn became the material basis for a democratic push led by the middle class. Could China take a similar path? asks Keun Lee, Distinguished Professor of Economics at Seoul National University and the author of China’s Technological Leapfrogging and Economic Catch-up: A Schumpeterian Perspective.

It is true that China may reach that level by the mid-2030s without competitive elections or even significant liberalization, he writes for Project Syndicate. Still, the next 10-15 years may open a window for democratization of the kind that Koreans scrambled through from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s. If so, it will be up to China’s leaders and people – especially middle-class Chinese – to take advantage.

Over the last dozen years, Beijing has slapped discriminatory sanctions on trading partners that interact with Taiwan or support democracy in Hong Kong, says Victor Cha, Professor of Government at Georgetown University and Senior Vice President for Asia at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. It has imposed embargoes on and fueled boycotts against countries and companies that speak out against genocide in Xinjiang or repression in Tibet. Indeed, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has gone after almost any entity that has crossed China in any way.

Beijing’s long-term objective is to force governments and companies to anticipate, respect, and defer to Chinese interests in all future actions. It seems to be working, he writes in How to Stop Chinese Coercion: The Case for Collective Resilience, an article for Foreign Affairs:

-

National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

Major democracies such as South Korea remained silent when China passed a national security law in Hong Kong suppressing democracy in 2020.

- In 2021, Brazil did not exclude the Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei from its 5G auction for fear of losing billions of dollars in business.

- In 2019, after the Gap clothing company released a T-shirt design with a map of China that did not include Taiwan and Tibet, it issued a public apology and removed the shirt from sale, even before Beijing said anything.

- After the salmon restrictions in 2010, Norwegian leaders refused to meet with the Dalai Lama when he visited in 2014.

- And according to reports and investigations by a variety of organizations…. Hollywood companies won’t produce films that cast China in a negative light for fear of losing ticket sales.

Part of China’s hubris in practicing economic coercion against its trade partners comes from confidence that the targets will not dare counter sanctions with concrete action. Beijing is right to be confident: it is hard for any single country to go up against an economic behemoth….To build a bloc that can stop Chinese coercion, Australia, Japan, South Korea, and the United States must first come to an agreement among themselves. The first three governments are the United States’ key allies in the Pacific, and all four nations are prominent market democracies and the core stakeholders in the region’s liberal political and economic order……

During the Cold War, Washington routinely countenanced illiberal practices to protect the liberal order—for example, supporting anticommunist military regimes in South Korea and Taiwan as bulwarks against more brutal nearby powers, adds Cha, a board member of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). Today, the West may need to compromise on its free trade principles if it wants to prevent Beijing from corrupting globalization. RTWT