Yalta shaped the post-war world, The Guardian reports.

Yalta shaped the post-war world, The Guardian reports.

Seventy-five years ago, on February 4-11, 1945, US President Franklin Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin met at the Yalta resort in then-Soviet Crimea to finalize their strategy for the remainder of World War Two and forge a post-war settlement, notes Daniel Fried, the Weiser Family distinguished fellow at the Atlantic Council. Yalta offers lessons.

- One is to be operationally serious: take care when negotiating documents based on general language of principles, like Yalta’s Declaration of Liberated Europe, with a leader who shares neither your values nor your underlying purposes. ….

- Another is be realistic about relative strength, especially in the short term: in its World War Two aims, the United States allowed a gap to develop between its principles and power on the ground. At Yalta, that gap left the United States without good options; it relied on rhetoric and hope instead. Yalta’s reputation for failed aspirations and naïve (or worse) retreat reflect the baleful consequences of doing so.

- A third lesson is that core values may have more viability than it seems, especially in the long term: for two generations after 1945, foreign policy professionals and scholars concluded that Roosevelt’s weak defense of Poland at and immediately after Yalta was pointless (or cynical) and that the principles of the Atlantic Charter were inapplicable east of the Iron Curtain. Soviet domination there, it was implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) accepted, was forever. But it turned out otherwise. ….

ACUS

That policy sought to fulfill the promise of the Atlantic Charter for all of Europe—and this time was more successful. Nor is that narrative over, adds Fried, (right), a board member of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). With respect to Ukraine, a country also seeking a future with an undivided Europe, those debates and those tensions apply to this day.

The leaders also agreed to democratic elections throughout liberated Europe – including for Poland, which would have a new government “with the inclusion of democratic leaders from Poland itself and from Poles abroad”, the BBC adds. But democracy meant something very different to Stalin. Though he publicly agreed to free elections for liberated Europe, his forces were already seizing key offices of state across central and eastern European countries for local communist parties.

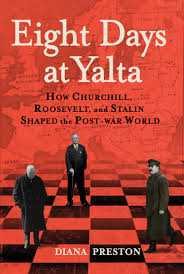

Among the most pressing issues were the borders and future democratic freedoms of Poland, which Roosevelt and Churchill had pledged to safeguard, notes the author of “Eight Days at Yalta: How Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin Shaped the Post-War World.” By February 1945, however, the Red Army was in control of most of Eastern Europe. As Stalin was fond of saying, “Whoever occupies a territory imposes on it his own social system,” and the Soviet Union was simply too powerful to resist.