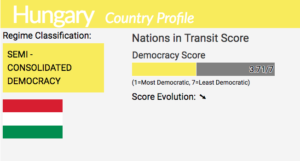

With an alarming rise in anti-Semitism and attacks on press and academic freedom, Hungarian democracy had another bad year in 2018, notes Brookings analyst William A. Galston. More than 400 private news outlets have been brought under the control of a holding company run by close allies of Viktor Orbán, including his personal lawyer and a lawmaker from his party, Fidesz, he writes for The Wall Street Journal:

With an alarming rise in anti-Semitism and attacks on press and academic freedom, Hungarian democracy had another bad year in 2018, notes Brookings analyst William A. Galston. More than 400 private news outlets have been brought under the control of a holding company run by close allies of Viktor Orbán, including his personal lawyer and a lawmaker from his party, Fidesz, he writes for The Wall Street Journal:

While proponents defend the move as promoting “balance” in Hungarian media, critics say it amounts to a thinly veiled return to a communist-style centralized state-media system. Adding credibility to the objections, Mr. Orbán issued a decree exempting the holding company from scrutiny by the agency charged with protecting competition against excessive concentration. Meanwhile, one of the two remaining major opposition newspapers shut down after the government ceased advertising in it.

While proponents defend the move as promoting “balance” in Hungarian media, critics say it amounts to a thinly veiled return to a communist-style centralized state-media system. Adding credibility to the objections, Mr. Orbán issued a decree exempting the holding company from scrutiny by the agency charged with protecting competition against excessive concentration. Meanwhile, one of the two remaining major opposition newspapers shut down after the government ceased advertising in it.

But a wave of protests is uniting Hungary’s divided opposition. For the first time, Orban may have something to worry about, The Economist notes:

Despite the modest numbers, the protests are significant because of the unity of the opposition, says Tamas Boros of Policy Solutions, a think-tank. The demonstrators come from two distinct sections of Hungarian society. One group, Mr Boros says, consists of veteran protesters “with ideological grievances against the regime. The other is people affected by the labour law, concerned about their everyday lives.” That could form a potent mixture.

Fidesz had 38 percent support in a November poll by pro-government think-tank Nezopont, while all the opposition parties had about 25 percent combined, Reuters adds:

Csaba Toth, director of liberal think tank Republikon (left), said the opposition was now working in rare unity and could build on this next year when Hungary holds European and municipal polls.

Csaba Toth, director of liberal think tank Republikon (left), said the opposition was now working in rare unity and could build on this next year when Hungary holds European and municipal polls.

“But if they are not able to come up with something forward-looking in the next few days before Christmas, the whole (protest sentiment) could collapse,” he said.

The European Commission and the Luxembourg court should state that if a member state abolishes judicial independence, the freedom of education or infringes on freedom of the press, it is equal to a breach of the constitutional guarantee of the Union, argues analyst Edit Zgut.

The European Commission and the Luxembourg court should state that if a member state abolishes judicial independence, the freedom of education or infringes on freedom of the press, it is equal to a breach of the constitutional guarantee of the Union, argues analyst Edit Zgut.

With this they could take the wind out of the sails of those who argue that it is still problematic to launch infringement procedures or politically sanction a member due to the violation of the rule of law because of the lack of proper codification of EU values, she writes for Visegrad Insight:

Also, if initiatives regarding the conditions of the rule of law will not be incorporated in such new mechanisms, it would be important to enforce at least the currently existing instruments of the Lisbon Treaty. As it has been rightly pointed out by R. Daniel Kelemen, an American political scientist, Article 142 of the Common Provisions Regulation currently allows suspension of payments in case of systematic violation of the rule of law. In order to avoid an irreversible proliferation of authoritarian hybrid regimes, the EU institutions have to enforce these multiple tools in a systemic and efficient manner.

Zgut’s article is part of the #DemocraCE project series run by Visegrad/Insight and Res Publica Foundation in cooperation with the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).