The weakening of Israel as a bastion of democracy in the Middle East is not in the interests of the western world, and could possibly become a danger to the western world, one observer suggests.

Israel’s attorney general Gali Baharav-Miara has instructed Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to end his involvement in current judicial overhaul efforts because he risked a conflict of interest. Baharav-Miara criticized the proposed legislation in a written opinion to Netanyahu’s justice minister, NPR reports.

However, says Suzie Navot of the Israel Democracy Institute, “The reform may move forward even if the attorney general will not defend the legislation.”

However, says Suzie Navot of the Israel Democracy Institute, “The reform may move forward even if the attorney general will not defend the legislation.”

Israel is on a political trajectory that places it among the world’s illiberal states, argues Steven A. Cook, the Eni Enrico Mattei senior fellow for Middle East and Africa studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. It would be inaccurate to suggest that Israel is just like Russia, which is just like India, which is just like Hungary, he writes for Foreign Policy.

Yet leaders in all of these countries share a similar outlook about how to organize their societies. So, yes, it is true that Jerusalem’s ties to Moscow are intertwined with its security concerns and the emergency that is Iran’s presence in Syria, Cook contends. But for those who think of Israel as a Western-oriented democracy, its relationships with Russia and other illiberal states are much more consequential than that.

It should be recognised that efforts to push back against current trends face two formidable impediments, notes Eran Rashiv, a professor of economics at Tel Aviv University and at the London School of Economics’ Centre for Macroeconomics: they require large-scale co-ordination among people and businesses, and they risk the break-up of society, he writes for The FT.

The weakening of Israel as a bastion of democracy in the Middle East is not in the interests of the western world. The possibility that it may change from a modern, dynamic, liberal democracy to a potentially illiberal, non-democratic, religious state is a danger to the western world. It is not just Israelis who should be concerned.

The weakening of Israel as a bastion of democracy in the Middle East is not in the interests of the western world. The possibility that it may change from a modern, dynamic, liberal democracy to a potentially illiberal, non-democratic, religious state is a danger to the western world. It is not just Israelis who should be concerned.

Israel’s lack of a written constitution may be contributing to the current crisis, experts suggest.

According to Dr. Guy Lurie, a research fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute, when Israel was established in 1948 there was an understanding that it would have a constitution, The Media Line reports. The first election to what would become the Knesset, the Israeli parliament, was supposed to also include electing members of a constituent assembly whose job was to draft the constitution.

But various divisions as to what should be the nature of the state prevented the constitution from being drafted, said Lurie. Among them were religion and its place in the state, and the flexibility that the government would have in using its power.

Israel’s government is moving to eviscerate the independence of the judiciary and remake the country’s democratic identity, according to leading journalists and authors Matti Friedman, Daniel Gordis and Yossi Klein Halevi. That initiative needs to be understood through three lenses: the substance of the proposed changes, the process by which they are being promoted and the identities of those pushing for the change, they write for The Times of Israel:

Israel’s government is moving to eviscerate the independence of the judiciary and remake the country’s democratic identity, according to leading journalists and authors Matti Friedman, Daniel Gordis and Yossi Klein Halevi. That initiative needs to be understood through three lenses: the substance of the proposed changes, the process by which they are being promoted and the identities of those pushing for the change, they write for The Times of Israel:

- In substance, the changes would remove the only effective brake on government power and profoundly weaken the only body capable of protecting citizens from the tyranny of a majority – protection that has never seemed more vital…..This is no “judicial reform,” but a dramatic alteration that would bring Israel’s governing system closer not to the US and Canada but to Hungary and Turkey.

- As for process, this radical transformation of Israel’s governing system is being pursued at breakneck speed without any national discussion, without having presented it to the electorate in any meaningful way before the recent elections, and without regard for criticism now coming from across the political and social spectrum. We agree that a constructive national discussion on legal reform is not only necessary but overdue. But that is impossible when the government refuses to slow its pace and engage in discussion aimed at genuine, rather than cosmetic, compromise.

- As for who is behind this initiative: A prime minister currently on trial for corruption, and who has appointed ministers with criminal records, is claiming legitimacy to overturn the legal system. Understandably, many of Israel’s supporters want to believe that Netanyahu is still a cautious conservative loyal to the country’s liberal DNA. In fact, though, he has become a very different kind of leader, one who subverts the national interest to his own. A wise leader encourages unity among his people; Netanyahu is stoking hatred and schism.

National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

The moves are akin to similar incremental shifts towards autocratic rule in formerly consolidated democracies. A Chilling Lesson for Israel From Hungary, Poland and Turkey: Democracy Dies Slowly runs the headline in today’s Haaretz.

Israel has enjoyed a democratic durability that is especially striking for three main reasons, notes Amichai Magen, the director of the Program on Democratic Resilience & Development at Reichman University’s Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy, and Strategy:

- First, the country’s geographical location. Living in a region of stable, peaceful, prosperous democracies is not an absolute guarantee of democratic health, but it does help. Yet Israel emerged and survived in an environment which, as Israeli historian, Alexander Yakobson, aptly put it, is “as favorable to liberal democracy as the Dead Sea is to fishing.”

- Second, the country’s demography. Neither Israel’s founding elites nor the bulk of its population come from societies with solid democratic values or institutions. On the contrary, as former Israeli Ambassador to the U.S. Michael Oren observed: “When Zionism emerged at the end of the 19th century, the Jews of Palestine and the thousands who joined them from tsarist Russia and around the Middle East had no exposure to democracy.” In the decades following its independence, Israel absorbed some two million immigrants, mainly from the Middle East, North Africa, and the former Soviet bloc, who similarly lacked exposure to democratic practice in their lands of origin……”

- Lastly, the durability of Israeli democracy is remarkable because of the country’s lack of a formal constitution. Israel has made do with a mixture of informal norms and Basic Laws (legislation passed piecemeal by the Knesset to establish the separation of powers, make the military subservient to elected authority, and guide the work of the executive, legislature, and courts). Eschewing the “winner takes all politics” of presidential and first-past-the-post political systems, Israel has relied upon a radical version of proportional representation in which teams of rivals representing wildly disparate ideologies and sectoral interests form a succession of messy coalition governments.

Netanyahu’s new government has put the country’s foundational democratic, tolerant and rational principles under greater pressure than Israel has seen before, according to Paul Berman, Martin Peretz, Michael Walzer and Leon Wieseltier. It is not just a matter of the proposed law restricting the power of the Supreme Court, the only check and balance in Israel’s system — a law that Netanyahu has proposed apparently for the corrupt purpose of rescuing himself from his own legal morass.

A number of racists, misogynists, homophobes and theocrats have taken powerful ministerial posts in his government, and the whole spirit of their enterprise is visibly hostile toward the culture of democratic tolerance and rationality, they write for The Post.

Three shadow-states

So why am I now deeply worried about the future of Israeli democracy? Magen writes for Persuasion. As with the United States, Brazil, and India, the causes of democratic backsliding in Israel are complex, and no one fully understands them yet. We can, however, point to several potent trends that threaten to unravel Israeli democracy:

- The first has to do with the state itself. From the outside, Israel appears to be a strong and effective state. The 2022 US & News Report, for example, ranks it as the 10th most powerful state in the world, with Israel’s military placed 4th, preceded only by the United States, China, and Russia. …..But this is increasingly a façade. Over the last few decades, Israel has allowed three shadow-states to gradually emerge under its nose: an ultra-Orthodox (or haredi) Jewish one, Bedouin-Arab areas of lawlessness and violence in the country’s rural regions, and a nationalist West Bank settler movement operating in a twilight-zone of ambiguous Israeli authority over the Palestinians. In each case, what began as fringe communities have metastasized into full-blown areas of limited statehood. Even if Israel manages to resolve the settlements issue, unless it can integrate its growing haredi and Bedouin populations into broadly liberal modernity, Israel will become increasingly balkanized and unstable.

- Last but not least, there is the hellish democratic conundrum of Israel’s continued occupation and security control over more than two million Palestinians in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. ….The inability to disengage from the Palestinians places Israeli democracy in an incrementally-tightening temporal vise. Continued control over a Palestinian population devoid of full political rights will exacerbate already delicate relations between Arabs and Jews within Israel itself, complicate efforts to expand the Abraham Accords between Israel and its Arab neighbors, and be a source of growing discomfort for the Western allies on which Israel depends for its economic, diplomatic, and military security.

Yet all is not lost, Magen adds. At the structural level, the current crisis could spur Israel to deeper systemic reforms. A grand package deal could come together in which constitutional reform strengthens the supervisory powers of the Knesset and judiciary, while answering executive demands for better governance and socio-economic integration of haredi and Arab communities. RTWT

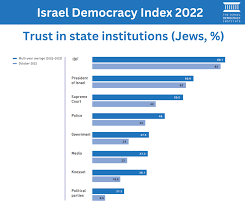

48% of Jewish Israelis currently perceive the right-left divide as the highest source of tension in society. These are some of the latest findings in IDI’s Israeli Voice Index. pic.twitter.com/weT5xZ2ceS

— Israel Democracy Institute (@IDIisrael) February 6, 2023

#Israel has shown exceptional democratic #resilience, but there are now several reasons to be concerned about the health of Israeli democracy, #AmichaiMagen writes for @JoinPersuasion. https://t.co/XzyxeeyauP

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) February 6, 2023