EU East Stratcom Task Force

Russia’s human rights situation is getting worse with each passing year, says Tatanya Lokshina of Human Rights Watch. The regime routinely “messes up” because it has destroyed almost all feedback loops and so lurches from the targeted repression of the past to a completely chaotic approach (HT: Paul Goble).

The activist destruction of feedback mechanisms means people have fewer ways to communicate their views to the regime, but also means the regime acts in counterproductive ways because it lacks information that could prevent it from making mistakes.

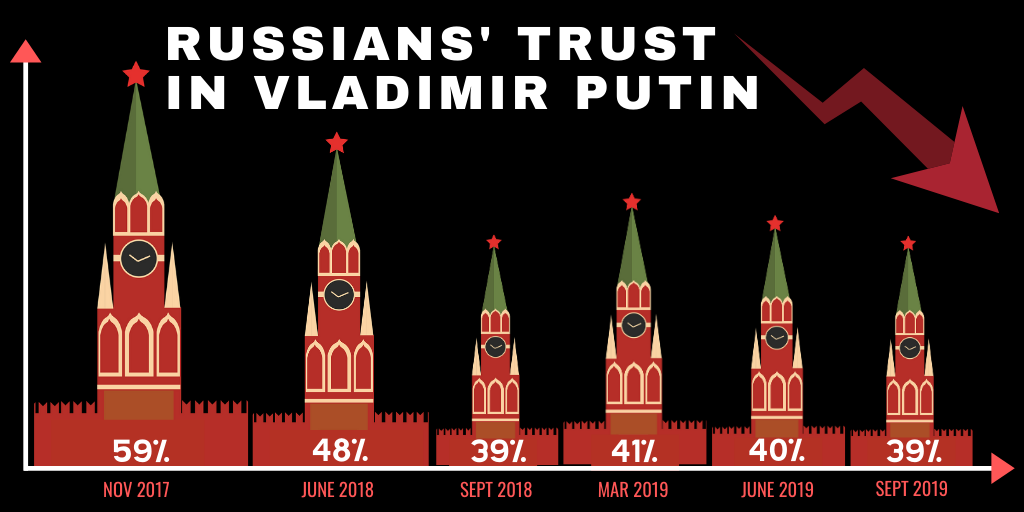

Levada

Only 39 percent of Russians express trust in Vladimir Putin; a number that has been falling for over a year, according to a survey from the independent Levada Center pollster. Almost one in four, 24 percent, could not name a single trustworthy person in Russian politics, the EU East Stratcom Task Force reports.

The Czech NGO People In Need has become the latest foreign group Russia’s Justice Ministry has placed on its blacklist of “undesirable” organizations, RFE/RL adds. Founded in 1992, People In Need is the 19th organization to be blacklisted since Russian President Vladimir Putin signed the “undesirable” law in 2015. Other groups blacklisted include the Atlantic Council; the Ukrainian World Congress; the National Endowment for Democracy; and the German Marshal Fund of the United States.

As Russian soft power is generally overlooked or dismissed in Western countries either as an outgrowth of Russian military power or as a result of rentseeking by some political entrepreneurs, its structural causes and long-term staying power is vastly underestimated, according to a new PONARS analysis, Five Faces of Russia’s Soft Power.

There are at least five different categories of foreign audiences that espouse a pro-Russian geopolitical identity, all united by an opposition to liberalism, argues Şener Aktürk, Associate Professor in the Department of International Relations at Koç University, Istanbul, Turkey. In addition to pro-Russian far right parties and networks, which have attracted most of the attention of scholars and journalists, there are also far left, Orthodox Christian, Russophone, and various ethnoreligious and separatist groups that favor a pro-Russian geopolitical identity.

There are at least five different categories of foreign audiences that espouse a pro-Russian geopolitical identity, all united by an opposition to liberalism, argues Şener Aktürk, Associate Professor in the Department of International Relations at Koç University, Istanbul, Turkey. In addition to pro-Russian far right parties and networks, which have attracted most of the attention of scholars and journalists, there are also far left, Orthodox Christian, Russophone, and various ethnoreligious and separatist groups that favor a pro-Russian geopolitical identity.

All five categories share the common ideological feature of hostility to liberalism, both in domestic politics and in international relations, the report adds. There are also a number of more specific concerns, such as opposition to same sex marriage and Muslim immigration, which multiple categories of pro-Russian groups share.

The Kremlin’s propaganda offensive, implemented and tested over the last decade, was initially intended as a tool to enhance Russia’s soft power, Marcel H. Van Herpen argues in Putin’s Propaganda Machine. But it quickly developed into a multifaceted information warfare strategy that makes use of diverse instruments, including:

The Kremlin’s propaganda offensive, implemented and tested over the last decade, was initially intended as a tool to enhance Russia’s soft power, Marcel H. Van Herpen argues in Putin’s Propaganda Machine. But it quickly developed into a multifaceted information warfare strategy that makes use of diverse instruments, including:

- mimicking Western public diplomacy initiatives

- hiring Western public-relations firms

- setting up front organizations

- buying Western media outlets

- financing political parties,

- organizing a worldwide propaganda offensive through the Kremlin’s cable network RT, and publishing paid supplements in leading Western newspapers.

In this information warfare, key roles are assigned to the Russian diaspora and the Russian Orthodox Church, the latter focused on spreading so-called traditional values and opposing universal human rights and Western democracy, he adds.

Putin’s regime falls into the category of a “grievance state” and modern Russia’s toxic blend of grievance and self-ascribed mission make its geopolitics dangerously revanchist and destabilizing, says a leading expert. The modern Russian regime promotes a kind of global restoration narrative, in which its self-assertive authoritarianism provides the vehicle for national or even civilizational resurrection, Dr. Christopher Ashley Ford writes in Ideological “Grievance States” and Nonproliferation: China, Russia, and Iran.

Putin’s regime falls into the category of a “grievance state” and modern Russia’s toxic blend of grievance and self-ascribed mission make its geopolitics dangerously revanchist and destabilizing, says a leading expert. The modern Russian regime promotes a kind of global restoration narrative, in which its self-assertive authoritarianism provides the vehicle for national or even civilizational resurrection, Dr. Christopher Ashley Ford writes in Ideological “Grievance States” and Nonproliferation: China, Russia, and Iran.

It is critical to the regime’s ideology that Russia deserves to be a great power and to exert its influence widely abroad. Thus are key themes of modern Russia’s ideologized self-perception entwined:

- a sense of identity obsessed by endless cycles of existential foreign threat;

- a feeling of mission and taste for martyrdom in resisting or even saving humanity from such evils;

- a mystical conception of civilizational purity that must be preserved against malign external forces and values, including by the maintenance of strongman rule at home; and

- a nostalgia for lost glory that can be regained through heroic effort and a willingness to take dramatic risks.

This hunger for a return to lost glory lies at the heart of the geopolitically revisionist agenda of the modern Russian “grievance state,” Ford contends. RTWT