Budapest’s response to the Coronavirus pandemic has been to suspend parliament and give Prime Minister Viktor Orbán open-ended powers to rule by decree. Will the latest move by the ruling Fidesz party cement authoritarianism in Europe? Deutsche Welle reports (above).

The changes of the past decade have laid the groundwork for an even more far-reaching legacy that will transform society at the roots and may outlast both Orban and his political system. Dramatic change has taken place at all levels of education, in research and cultural institutions and in the economic system, the FT’s Valerie Hopkins writes:

One institution unlikely to come under threat is the controversial House of Terror. The museum, which opened in 2002 during Orban’s first term, is part of his attempt to tailor the country’s historical narratives. … The research director is Marton Bekes, a 37-year-old who also edits Kommentar, a journal that can often be seen on Orban’s desk during video addresses. Bekes shares the prime minister’s view that if you own culture, you can “do a whole era”. “You can lose elections – it is better if you don’t – but even if you do, cultural hegemony is yours,” he says. ….Bekes is hopeful that Orban will be in charge of Hungary for “tens of more years”. “This cultural work is a long march,” he concludes. “But we don’t yet have cultural hegemony, so we have to keep winning elections.”

“They want to take over all aspects of Hungarian life, and I think they have gone pretty far,” says Andras Biro-Nagy, the director of Policy Solutions, an independent Budapest think-tank that is often critical of the government.

It’s the culture, stupid!

The same month that Orban set out his plan for a “cultural era”, Hungary’s kindergarten curriculum was amended to promote a “national identity, Christian cultural values, patriotism, attachment to homeland and family”…..Creating enemies and vilifying opponents is part of the strategy, Hopkins adds.

The same month that Orban set out his plan for a “cultural era”, Hungary’s kindergarten curriculum was amended to promote a “national identity, Christian cultural values, patriotism, attachment to homeland and family”…..Creating enemies and vilifying opponents is part of the strategy, Hopkins adds.

“The biggest lesson in this decade regarding everyday life is that life can change from one moment to another, which is not typical in a stable democracy where rule of law prevails,” says Peter Kreko, the director of Political Capital, a Budapest-based think-tank, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). “You can lose your job [due to political reasons]. Universities can be pushed out from one moment to another. Orban’s policy and politics is not conservative. This is about a permanent illiberal revolution.”

China’s Communist Party isn’t the only illiberal power mounting an ambitious ideological campaign.

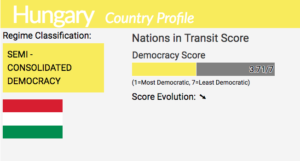

This month, the pro-democracy group Freedom House officially announced that it no longer considered Hungary a democracy. But for some in the West, Viktor Orbán is not viewed as a warning. He’s viewed as a role model, Vox’s Zack Beauchamp writes:

Orbán’s effort to cultivate Western intellectuals — funding their work, inviting them to meet with him as honored guests in Budapest, speaking at their glitzy conferences — is part of a much more ambitious ideological campaign. He describes himself as the avatar of a new political model spreading across the West, which he terms “illiberal democracy” or “Christian democracy.”

Orbán’s effort to cultivate Western intellectuals — funding their work, inviting them to meet with him as honored guests in Budapest, speaking at their glitzy conferences — is part of a much more ambitious ideological campaign. He describes himself as the avatar of a new political model spreading across the West, which he terms “illiberal democracy” or “Christian democracy.”

Rod Dreher, a senior editor at the American Conservative, one of a handful of influential Western writers courted by offers “general endorsement” rooted in a sense that the Hungarian leader challenges the liberal elite in a way few others do. In Dreher’s analysis, the dominant mode of thinking in the West is secular and liberal — a political style that suffocates traditional religious observance and crushes specific national identities in favor of a homogenizing, cosmopolitan ideal, Beauchamp adds.

National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

“He [Orbán] knew that in 2015, to allow all the Middle Eastern immigrants to settle in Hungary would have been surrendering a Hungarian future for the Hungarian people…and all the traditions and cultural memories they carry with them,” said Dreher. “Broadly speaking, the ideology of globalism presumes that those traditions and those memories are obstacles to creating an ideal world. That they are problems to be solved rather than a heritage to be cherished.”

In an exclusive interview with DW’s Conflict Zone, Member of the European Parliament, Balazs Hidveghi of the Fidesz party, defended the emergency measures passed by the Hungarian government in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. From the Fidesz party headquarters in Budapest, Hidveghi told DW’s Tim Sebastian the legislation was passed in accordance with the Hungarian constitution, and that: “rule of law works in Hungary very well.”