A new official summation of Communist Party history is likely to exalt Xi Jinping as a peer of Mao and Deng, fortifying his claim to a new phase in power. A high-level meeting opening in Beijing will issue a “resolution” officially reassessing the party’s 100-year history that is likely to cement his status as an epoch-making leader alongside Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, the New York Times reports:

A new official summation of Communist Party history is likely to exalt Xi Jinping as a peer of Mao and Deng, fortifying his claim to a new phase in power. A high-level meeting opening in Beijing will issue a “resolution” officially reassessing the party’s 100-year history that is likely to cement his status as an epoch-making leader alongside Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, the New York Times reports:

While ostensibly about historical issues, the Central Committee’s resolution — practically holy writ for officials — will shape China’s politics and society for decades to come. The touchstone document on the party’s past, only the third of its kind, is sure to become the focus of an intense indoctrination campaign.

“This is about creating a new timescape for China around the Communist Party and Xi in which he is riding the wave of the past towards the future,” said Geremie R. Barmé, a historian of China. “It is not really a resolution about past history, but a resolution about future leadership.”

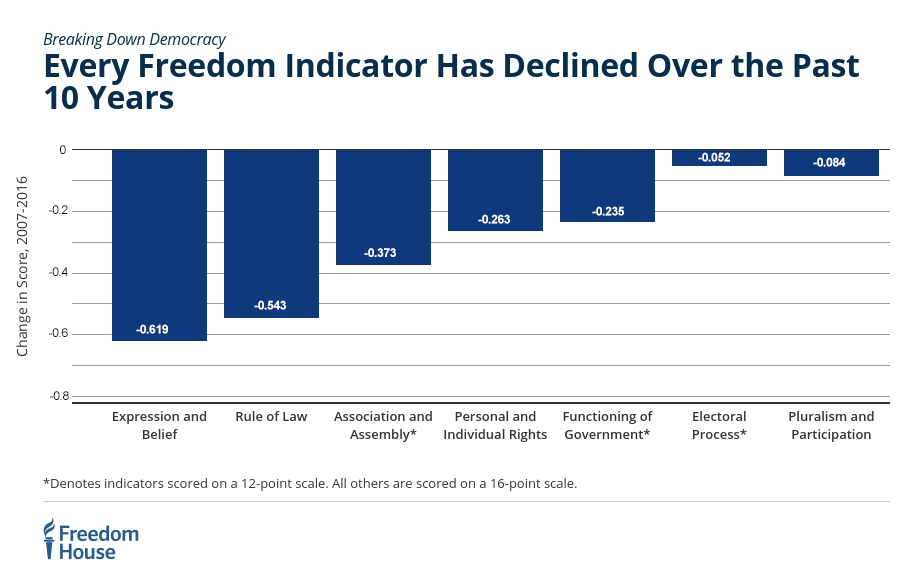

Modern authoritarians have developed the means to control the commanding heights of the media, the mechanisms of elections, the police and military, civil society, minority groups, and the economy. More recently, they have focused on another crucial category of democratic life: history and culture, notes Arch Puddington, the author of the Freedom House Special Report, Breaking Down Democracy: The Goals, Strategies, and Methods of Modern Authoritarians (2017).

In autocracies large and small, brutal and relatively relaxed, historical revisionism has emerged as a regime priority nearly as important as crony capitalism or control of the judiciary, he writes for the American Purpose:

There are no honest discussions in China or Russia about police abuse, defendants’ rights, the persecution of minorities, or the rights of believers who resist state control. Xi Jinping’s “Seven Don’t Mentions” stands as a foundational document in thought control. It’s worth taking careful note of the forbidden subjects it singles out: universal values, civil society, civic freedom, an independent judiciary, and press freedom. These are the building blocks of democracy, the very institutions that impressed Tocqueville during his American tour. More recently, they inspired millions during the final decades of the 20th century, and they continue to inspire people in dictatorships like Belarus and in countries like Taiwan and Ukraine that are menaced by neighboring dictatorships.

In an effort to bury emancipative values under the soil of nationalism and religion, autocrats and populists compose narratives about national destinies and geopolitical missions to breed a “culture of allegiance,” Christian Welzel wrote for the Journal of Democracy.

An editorial in the CCP’s propaganda outlet, China Daily, recently questioned a narrative in which democracy “appears to be vested exclusively with Western criteria and traits,” insisting instead that it is not a monopoly of the West or a specific political system but merely an ill-defined “set of values in a given society.”

The enemies of freedom have pushed the false narrative that democracy is in decline because it is incapable of addressing people’s needs, Freedom House observes. In fact, democracy is in decline because its most prominent exemplars are not doing enough to protect it. Global leadership and solidarity from democratic states are urgently needed.

The enemies of freedom have pushed the false narrative that democracy is in decline because it is incapable of addressing people’s needs, Freedom House observes. In fact, democracy is in decline because its most prominent exemplars are not doing enough to protect it. Global leadership and solidarity from democratic states are urgently needed.

The Cold War classic, The God That Failed, feels increasingly relevant as more and more young people are pulled in by ideological extremes, Middlebury College Professor Shalom Goldman writes for the Tablet.

Four narratives have emerged from America’s failure to sustain and enlarge the middle-class democracy of the postwar years. They all respond to real problems. Each offers a value that the others need and lacks ones that the others have, George Packer writes for the Atlantic;

- Free America celebrates the energy of the unencumbered individual.

- Smart America respects intelligence and welcomes change.

- Real America commits itself to a place and has a sense of limits.

- Just America demands a confrontation with what the others want to avoid.

They rise from a single society, and even in one as polarized as ours they continually shape, absorb, and morph into one another, Packer adds. But their tendency is also to divide us, pitting tribe against tribe. These divisions impoverish each narrative into a cramped and ever more extreme version of itself.

Mr. Xi’s conception of history offers “an ideological framework which justifies greater and greater levels of party intervention in politics, the economy and foreign policy,” said Kevin Rudd, a former Australian prime minister who speaks Chinese and has had long meetings with Mr. Xi, the Times adds:

Mr. Xi’s conception of history offers “an ideological framework which justifies greater and greater levels of party intervention in politics, the economy and foreign policy,” said Kevin Rudd, a former Australian prime minister who speaks Chinese and has had long meetings with Mr. Xi, the Times adds:

“He has this visceral notion that as the son of a revolutionary, Xi Zhongxun, that he cannot allow the revolution simply to drift away,” said Mr. Rudd, now president of the Asia Society. Mr. Xi has also often cited the Soviet Union as a warning for China, arguing that it collapsed in part because its leaders failed to eradicate “historical nihilism” — critical accounts of purges, political persecution and missteps that corroded faith in the communist cause.

China’s ruling Communist Party (CCP) advances its interests by manipulating local narratives through information operations, interfering in political processes and promoting an authoritarian governance model, notes the International Republican Institute.

Daniel Chirot has written that “not having a unifying history can permanently cripple a nation’s ability to cope with major crises,” Puddington observes:

The growing disillusionment with liberalism is welcome news for America’s adversaries. Modern authoritarians fear American-style democracy; understand the subversive power of liberal ideas; and are going to extraordinary lengths to destroy nascent democratic institutions and to suppress discussion of concepts like individual rights, civil liberties, and freedom of expression.

It also explains why…..

Xi “sees history as a tool to use against the biggest threats to Chinese Communist Party rule,” said Joseph Torigian, an assistant professor at American University who has studied Mr. Xi and his father. “He’s also someone who sees that competing narratives of history are dangerous.” he tells the Times.

Xi “sees history as a tool to use against the biggest threats to Chinese Communist Party rule,” said Joseph Torigian, an assistant professor at American University who has studied Mr. Xi and his father. “He’s also someone who sees that competing narratives of history are dangerous.” he tells the Times.

In the global battle of narratives, the case for democracy remains strong, argues International IDEA’s Kevin Casas-Zamora, who cites three key arguments:

To a much greater degree than any other political system democracy allows for the correction of policies – a function of its allowing the free circulation of information, but also of the possibilities for collective action built into the system…. Democracy matters for key tenets of sustainable development, such as gender equality….Democracy respects our agency and inherent dignity.

To Steer China’s Future, Xi Is Rewriting Its Past https://t.co/8b5KPp6cN2

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) November 8, 2021