Beijing is buying up media outlets and training scores of foreign journalists as part of a worldwide propaganda campaign of astonishing scope and ambition, say Louisa Lim and Julia Bergin. China’s rapid media expansion across the world, is intended, in the words of President Xi Jinping, is to “tell China’s story well”. In practice, telling China’s story well looks a lot like serving the ideological aims of the state, they write for The Guardian:

Beijing is buying up media outlets and training scores of foreign journalists as part of a worldwide propaganda campaign of astonishing scope and ambition, say Louisa Lim and Julia Bergin. China’s rapid media expansion across the world, is intended, in the words of President Xi Jinping, is to “tell China’s story well”. In practice, telling China’s story well looks a lot like serving the ideological aims of the state, they write for The Guardian:

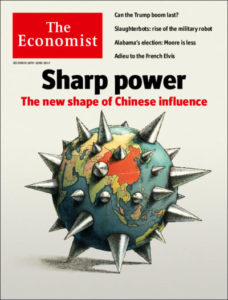

Though Beijing’s propaganda offensive is often shrugged off as clumsy and downright dull, our five-month investigation underlines the granular nature and ambitious scale of its aggressive drive to redraw the global information order. This is not just a battle for clicks. It is above all an ideological and political struggle, with China determined to increase its “discourse power” to combat what it sees as decades of unchallenged western media imperialism.

China’s ‘sharp power’ challenge to democracy is a theme of the new Power 3.0 podcast – a complement to the Power 3.0 blog – from the National Endowment for Democracy’s International Forum for Democratic Studies:

Tune in to @ThinkDemocracy’s new podcast, “Power 3.0 | Authoritarian Resurgence, Democratic Resilience.” Hosts @Walker_CT @ShanthiKalathil discuss China and the Global Challenge to Democracy w/ @larrydiamond @jodemocracy. Listen to @ThinkDemocracy’s inaugural Power 3.0 podcast episode featuring @LarryDiamond @HooverInst on the range of Beijing’s foreign influence and interference activities that target the institutions of democracies #China #SharpPower

Will China’s investments reshape Africa’s Internet?

Will China’s investments reshape Africa’s Internet?

Beijing’s vision of “Internet sovereignty,” promotes state control of online activity within a country’s borders as a matter of political security, without regard for free expression, notes Emeka Umejei, a research associate in the department of media studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa.

As ICT infrastructure backed by Beijing becomes increasingly prevalent on the African continent, it is important to examine the extent to which it will contribute to the replication of an authoritarian model of Internet governance with adverse consequences for democracy, freedom of expression, and human rights, he writes for Power 3.0. This can still be mitigated, but only if African civil society, media, policymakers, and academics deepen their understanding of Beijing’s engagement and debate its potential impact, while resisting digital power grabs by their own governments.

Some observers argue the expansion of authoritarian propaganda networks – such as Russia’s RT and Iran’s Press TV – has been overhyped, with little real impact on global journalism. But Beijing’s play is bigger and more multifaceted,  Lim and Bergin add:

Lim and Bergin add:

At home, it is building the world’s biggest broadcaster by combining its three mammoth radio and television networks into a single body, the Voice of China. At the same time, a reshuffle has transferred responsibility for the propaganda machinery from state bodies to the Communist party, which effectively tightens party control over the message. Overseas, capitalising on the move from analogue to digital broadcasting, it has used proxies like such as StarTimes to increase its control over global telecommunications networks, while building out new digital highways.

“The real brilliance of it is not just trying to control all content – it’s the element of trying to control the key nodes in the information flow,” says Freedom House’s Sarah Cook. “It might not be necessarily clear as a threat now, but once you’ve got control over the nodes of information you can use them as you want.”