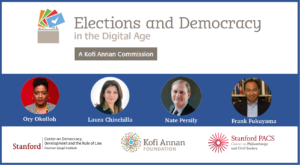

Kofi Annan Commission on Elections and Democracy in the Digital Age

In the span of just two years, the widely shared utopian vision of the internet’s impact on governance has turned decidedly pessimistic, notes Stanford Law School analyst Nate Persily. The original promise of digital technologies was unapologetically democratic: empowering the voiceless, breaking down borders to build cross-national communities, and eliminating elite referees who restricted political discourse, he writes in The Internet’s Challenge to Democracy: Framing the Problem and Assessing Reforms, a new report for the Kofi Annan Commission on Elections and Democracy in the Digital Age:

That promise has been replaced by concern that the most democratic features of the internet are, in fact, endangering democracy itself. Democracies pay a price for internet freedom, under this view, in the form of disinformation, hate speech, incitement, and foreign interference in elections. They also become captive to the economic power of certain platforms, with all the accompanying challenges to privacy and speech regulation that these new, powerful information monopolies have posed.

That promise has been replaced by concern that the most democratic features of the internet are, in fact, endangering democracy itself. Democracies pay a price for internet freedom, under this view, in the form of disinformation, hate speech, incitement, and foreign interference in elections. They also become captive to the economic power of certain platforms, with all the accompanying challenges to privacy and speech regulation that these new, powerful information monopolies have posed.

Seven D’s of Reform

Reform options to combat digital dangers to democracy are varied; the sources of reform are governments, the platforms, or civil society; most reforms come with costs; and they fall into several categories – the Seven D’s, Persily adds:

- Deletion – The takedown of content or the removal of accounts deemed to be dangerous.

- Demotion – Tweaking algorithms to reduce the exposure of users to dangerous speech, while retaining the speech or speaker on a given platform.

- Disclosure – Providing users with information as to the identity of speakers or the origin of communication to equip them to discount speech from certain people or places.

- Delay – Putting brakes on virality by slowing down the spread of all online communication or some subset deemed problematic.

- Dilution and Diversion – Combatting “bad” speech with “good” speech either by “flooding the zone” with healthy content or redirecting users’ attention toward better sources of information

- Deterrence – Raising the costs on bad actors by credibly promising an array of punishments, ranging from financial and reputational sanctions to offline uses of force.

- Digital Literacy – Educating users to become more discerning consumers of information and more skilled in understanding the platforms on which communication takes place.

The Road to Digital Unfreedom is the theme of the latest issue of the NED’s Journal of Democracy.

The Road to Digital Unfreedom is the theme of the latest issue of the NED’s Journal of Democracy.

Some media outlets are much more susceptible to disinformation, propaganda, and outright falsehoods (as judged by neutral fact-checking organizations such as PolitiFact), according to the New Yorker’s Jane Mayer.

Rather than “symmetric polarization” in left-leaning and right-leaning media outlets, she notes, the two poles of the media ecosystem function very differently, according to an analysis of millions of news stories by Yochai Benkler, Robert Faris and Hal Roberts, for their 2018 book, “Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation and Radicalization in American Politics.”

Have social media firms undermined democratic governance, “foster[ing] the deterioration of democratic and intellectual culture around the world,” as Siva Vaidhyanathan”s Anti-Social Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy suggests?

Have social media firms undermined democratic governance, “foster[ing] the deterioration of democratic and intellectual culture around the world,” as Siva Vaidhyanathan”s Anti-Social Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy suggests?

Readers are given the impression that the case against Facebook is closed, when in fact major debates around digital media and democracy are nowhere near settled, says Oxford University’s Robert Gorwa. This includes topics like online polarization and “filter bubbles,” disinformation and “fake news,” and the mental health impact of social media “addiction,” he writes for the LA Review of Books:

Did Russian interference really have a significant effect on the 2016 election, and, if so, how do we measure those effects? Do meaningful “filter bubbles” exist when observed in the broader context of people’s offline and online lives? These issues are complex and difficult to study, and it is a shame that the book did not engage with the many dissenting scholarly voices who warn against uncritically succumbing to the hype around “filter bubbles,” tech “addiction,” and so on.

“We should, in other words, be wary of tech-shaming insofar as it lulls us away from the difficult realities of messy societal divisions, deteriorating institutions, and other key drivers of today’s multifaceted democratic crises,” Gorwa suggests.

“We should, in other words, be wary of tech-shaming insofar as it lulls us away from the difficult realities of messy societal divisions, deteriorating institutions, and other key drivers of today’s multifaceted democratic crises,” Gorwa suggests.

Make no mistake, computational propaganda attacks are directed against democracy and human rights, but there is still a marked need for rigorous, scientific research to understand the relationship between computational propaganda and democratic processes, adds Belfer Fellow Samuel Woolley of the ADL Center for Technology and Society, and co-author of Computational Propaganda: Political Parties, Politicians, and Political Manipulation on Social Media:

We must work to generate knowledge about both the supply and demand sides of digital disinformation. With the former, who funds or undertakes these campaigns and why? To what extent are social media companies culpable, and who else bears the blame? With the latter, what happens psychologically to people who consume large amounts of disinformation? Do their votes change? Most crucially, how are minority communities affected?

An overwhelming majority of Europeans would support a radical new measure that would require social media companies to direct all users who have seen false information toward fact-checks, according to new polling from global advocacy group Avaaz, in collaboration with the polling group YouGov, TIME magazine reports:

An overwhelming majority of Europeans would support a radical new measure that would require social media companies to direct all users who have seen false information toward fact-checks, according to new polling from global advocacy group Avaaz, in collaboration with the polling group YouGov, TIME magazine reports:

The initiative is intended to prevent the spread of “fake news” on Facebook and Twitter as governments come under growing pressure to regulate social media. Research shared exclusively with TIME shows that 86.6% of people support Avaaz’s new proposal known as Correct the Record, which activists and politicians say could be the most effective way to stop “fake news” from spreading online.

The European Values Think-Tank is adding a new Security Strategies Program to its existing Kremlin Watch and Internal Security programs. The initiative will be led by Czech senior diplomat Martin Svárovský, who has served at the Czech Foreign Affairs Ministry for 19 years. He can be followed at twitter.com/martinsvarovsky.

The European Values Think-Tank is adding a new Security Strategies Program to its existing Kremlin Watch and Internal Security programs. The initiative will be led by Czech senior diplomat Martin Svárovský, who has served at the Czech Foreign Affairs Ministry for 19 years. He can be followed at twitter.com/martinsvarovsky.

Can democracy be saved from datacracy? asks Bhaskar Chakravorti, the Executive Director of Fletcher’s Institute for Business in the Global Context. The potential for digital damage is greatest to democracies in the “Digital South,”: according to the Digital Evolution Index, published in the Harvard Business Review, demarcates two distinct zones on the digital atlas:

A disproportionate number of the countries that have not as yet reached their full digital potential are embracing the technology much faster than the capacity of human beings, institutions and other cultural, regulatory and policy guardrails that can provide adequate safeguards. These countries are also ones where we found that users exhibit more trust in the digital systems and embrace it with fewer questions asked. …Here, lives can be lost, as was the case in India and Myanmar and “unprecedented industrial use of disinformation as a campaign strategy” can become a hallmark of an election, as was the case in Brazil.

disinfo portal

Fake news has become big news. Post-truth is the new paradigm, adds Eurozine. And behind it all, the spectre of an illiberal international waging ‘info-war’ against western democracies.

In an effort to advance the transatlantic partnership on countering disinformation as national and EU parliamentary elections approach, the Atlantic Council will host a series of events in Europe in March 2019 as part of #DisinfoWeek Europe. Events include “Disinformation: Actors Tools, and Solutions,” with Daniel Fried, a distinguished fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Future Europe Initiative and Eurasia Center [and National Endowment for Democracy board member]. Check out the Disinfo Portal for regular updates.

Kofi Annan Commission on Elections and Democracy in the Digital Age