The elections in Iraq and Lebanon earlier this month present a fragile but important counterpoint to a region in turmoil, notes Tamara Cofman Wittes, a Senior Fellow at Brookings’ Center for Middle East Policy. Extremists claim that only violence can bring change; these elections promise another path. And when Lebanon and Iraq pull off free elections under such trying circumstances, it’s harder for strongmen in other Arab states to argue that they can’t afford the risk to stability of allowing their own peoples a choice in who governs them, she writes.

The elections in Iraq and Lebanon earlier this month present a fragile but important counterpoint to a region in turmoil, notes Tamara Cofman Wittes, a Senior Fellow at Brookings’ Center for Middle East Policy. Extremists claim that only violence can bring change; these elections promise another path. And when Lebanon and Iraq pull off free elections under such trying circumstances, it’s harder for strongmen in other Arab states to argue that they can’t afford the risk to stability of allowing their own peoples a choice in who governs them, she writes.

The political outcomes in these two countries offer both risks and opportunities for American policy, and we must be wary of drawing strong conclusions from ambiguous results. That said, there are some developments* worth noting and nurturing in both Iraq and Lebanon, adds Wittes, who co-chaired an

NDI

international election observation mission in Lebanon for the National Democratic Institute [a core institute of the National Endowment for Democracy].

- In both Iraq and Lebanon, elections yielded lower turnout than in past years—49 percent in Lebanon and just 44 percent in Iraq. Both those who voted and those who stayed home expressed impatience with established political movements more interested in dividing the spoils of government than in actually governing.

- In both places, security gains have increased citizens’ appetite for pragmatic policies that deliver on their core needs.

- In both countries, the military and security services are relatively trusted national institutions, and nationalism is growing relative to sectarianism.

While some Iraqi secular democrats joined the illiberal Sadrist movement in a winning coalition, Lebanese civil society groups fared less well, running largely technocratic candidates on independent lists.

While some Iraqi secular democrats joined the illiberal Sadrist movement in a winning coalition, Lebanese civil society groups fared less well, running largely technocratic candidates on independent lists.

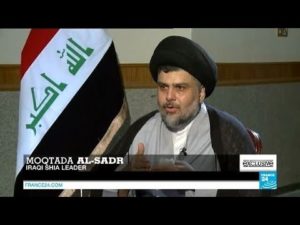

Iraq’s election saw the reinvention of Muqtada al-Sadr, from sectarian militia leader to populist, nationalist anti-corruption crusader, says Mohamad Bazzi, Associate Professor of Journalism at New York University. As with other Islamist groups in the Middle East, the Sadrist movement has built a formidable social and political organization that can deliver votes, he writes for Foreign Affairs:

Aside from his family’s pedigree, Sadr has another claim to leadership that his followers use to burnish his legitimacy over many other Iraqi leaders: he did not leave Iraq to live in exile during Hussein’s brutal rule. After Hussein’s ouster …. Sadr’s followers seized control of hospitals, schools, and mosques in parts of Baghdad, Najaf, and Karbala. They provided social services in the absence of a central government.

Aside from his family’s pedigree, Sadr has another claim to leadership that his followers use to burnish his legitimacy over many other Iraqi leaders: he did not leave Iraq to live in exile during Hussein’s brutal rule. After Hussein’s ouster …. Sadr’s followers seized control of hospitals, schools, and mosques in parts of Baghdad, Najaf, and Karbala. They provided social services in the absence of a central government.

Sadr has worked to change his image from firebrand to centrist, Tamer El-Ghobashy and Mustafa Salim write for the Washington Post:

In 2016, he latched onto a popular protest movement against corruption that demanded political reforms. He bolstered the demonstrations with his thousands of supporters and built ties with secular parties.

The Sadr movement’s base is made up largely of poor, disaffected young Shiites, says NPR’s Jane Arraf. His strong showing tapped into a deep vein of anger among Iraqis over poverty, ineffective public services, lack of jobs and rampant corruption.

The Sadrist Movement fragmented in 2008 as a result of the U.S. military surge, competition among internal factions, and Prime Minister Maliki’s consolidation of power, according to a report from the Institute for the Study of War.

The Sadrist Movement fragmented in 2008 as a result of the U.S. military surge, competition among internal factions, and Prime Minister Maliki’s consolidation of power, according to a report from the Institute for the Study of War.

“While the political and military power of the movement has declined, its traditional constituency; the urban Shi’a poor and rural Shi’a tribes; remains a large and politically-valuable electorate,” it noted, adding that two main factions were competing for control of the traditional Sadr constituency; the clerics and politicians (including al-Sadr) who emphasize a return to social, religious and educational programs [Dawa]; and the Mahdi Army, the movement’s paramilitary faction.

The movement’s commitment to Dawa blends interests – addressing constituent’s socio-economic needs – and ideology.

Large amounts of money are spent through the movement’s religious and social structures in part to “educate” youngsters on the virtues of the “Islamic regime,” the “vice” of the West, the conspiracy against Muslims, notes USIP analyst Elie Abouaoun.

“In the long run, al-Sadr and his organization are ill-equipped to engage in the business of governance; they lack the capacity to translate mobilization into public policy and ultimately are part of the problems that plague Iraq,” according to Ranj Alaaldin, a Visiting Fellow at Brookings Doha Center. “Through the sheer pressure of mobilizing the masses, the Sadrist movement could, nevertheless, engineer the space that allows for a culture of accountability to emerge, which Iraq’s reformist actors could then capitalize on, with the necessary support from the region and the international community,” he argued:

Indeed, al-Sadr will have to muster the necessary support from Iraq’s reformists, including a civil society that has played an important role in galvanizing people onto the streets. It also requires working with Western-aligned actors like Prime Minister Abadi, who in response to Sadrist protests has attacked al-Sadr and challenged his reform rhetoric on the basis that his own cronies and supporters are responsible for corruption and instability.

Indeed, al-Sadr will have to muster the necessary support from Iraq’s reformists, including a civil society that has played an important role in galvanizing people onto the streets. It also requires working with Western-aligned actors like Prime Minister Abadi, who in response to Sadrist protests has attacked al-Sadr and challenged his reform rhetoric on the basis that his own cronies and supporters are responsible for corruption and instability.

The escalating demands of Lebanon’s citizens for effective government services and the rise of a newly energized civil society led to the emergence of an unprecedented number of independent candidates, who eschewed affiliation with patronage-based, confessional movements and in some places challenged them directly, adds Brookings’ Wittes.

Some 66 civil society candidates agreed on a common political program under the umbrella of Killuna Watani, meaning ‘all for one nation,’ analyst Anchal Vohra observed. The candidates first emerged in 2015 as citizen’s groups under the rubric Beirut Madinati or ‘Beirut is my city’ to contest the municipal elections that year. “While they did well, they failed to secure a majority and couldn’t get the real power.”

Similar problems plagued civil society candidates this year, Vohra adds:

It has been hard for many of them to agree on common ideas. Clashing egos have also made consensus tougher. Funding is the other factor that may end up ruining prospects..[with candidates] banking on personal savings and help from friends to fight the polls, while established political parties have several sources to procure funds, including backing from foreign countries. Days before the polls, most civil society candidates are missing from the hoardings and posters plastered on the walls of Beirut. …A fragmented front facing scarcity of funds, the civil society candidates may just be a city phenomenon.

“Apolitical civil-society candidates focusing on improving state services and cutting back corruption created an element of excitement in a race mostly dominated by traditional political forces,” Middle East Eye’s Ali Harb observed. “Still, these activists are criticised for failing to run under a unified front. And broad ideas like ‘fighting corruption’ risk smashing against the hard reality of a Lebanese political system based on clientelism.”

A recent survey finds that the more effective and significant form of clientelism in Lebanon involves long-term relationships, in which voting for patrons becomes a social obligation. The survey also suggests that Lebanese voters have undeniable sectarian affinities, over and above material considerations, notes Amanda Rizkallah, an assistant professor of international studies at Pepperdine University.

A recent survey finds that the more effective and significant form of clientelism in Lebanon involves long-term relationships, in which voting for patrons becomes a social obligation. The survey also suggests that Lebanese voters have undeniable sectarian affinities, over and above material considerations, notes Amanda Rizkallah, an assistant professor of international studies at Pepperdine University.

Moving forward, these findings predict an uphill battle for nonsectarian civil society groups. Despite these concerns, civil society candidates are making their mark. They have built national alliances, shifted the public discourse and forced traditional elites to take programmatic positions, she writes for the Washington Post:

My research suggests that parties with civil war histories have more cohesive organizations, multigenerational networks of supporters and credentials as communal protectors in times of crisis. Hezbollah, Amal and the PSP were able to translate these assets into electoral gains immediately after the civil war period. …The Future Movement lacks this wartime organizational legacy. Research on previous election cycles demonstrates that the Future Movement plays an exclusively electoral game, making small payments to a wider array of voters. Its networks are shallow.

My research suggests that parties with civil war histories have more cohesive organizations, multigenerational networks of supporters and credentials as communal protectors in times of crisis. Hezbollah, Amal and the PSP were able to translate these assets into electoral gains immediately after the civil war period. …The Future Movement lacks this wartime organizational legacy. Research on previous election cycles demonstrates that the Future Movement plays an exclusively electoral game, making small payments to a wider array of voters. Its networks are shallow.

*These trends present opportunities for new moderating political forces to emerge—but also present the risk that, if citizens’ needs aren’t addressed, they might simply give up on electoral politics and on the government itself as a source of solutions to their day-to-day problems. Extremists could exploit this frustration. The United States has a stake in supporting healthy political competition, Wittes adds:

- In neither country did the electoral outcome significantly shift the balance of power between Iran’s allies and its adversaries. The battle to contain and push back Iranian influence is not lost, but neither is it over.

- In Iraq, the process of government formation will be more important to determining Iran’s role than the election itself was. While the United States cannot determine the outcome of Iraq’s government negotiations, it does have influence…

- In Lebanon, it’s not quite right to say that Hezbollah “won” these elections. In fact, it “won” the political game back in October 2016 when Saad Hariri cut a deal with Hezbollah to return as prime minister a few months after Saudi Arabia cut off aid to the Lebanese government and abandoned him. That deal seems to hold in the wake of the elections. ….

Wittes testified before the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Middle East and North Africa about the elections in Iraq and Lebanon. Her full testimony is available here. Video of the hearing, which included Danielle Pletka of the American Enterprise Institute and Michael Doran of the Hudson Institute, is available here.